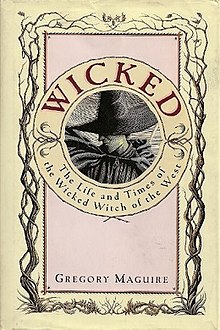

Wicked (Maguire novel)

First edition | |

| Author | Gregory Maguire |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Douglas Smith |

| Cover artist | Douglas Smith |

| Language | English |

| Series | The Wicked Years |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Publisher | ReganBooks |

Publication date | 1995 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 560 |

| ISBN | 0-06-039144-8 |

| OCLC | 32746783 |

| 813/.54 20 | |

| LC Class | PS3563.A3535 W5 1995 |

| Followed by | Son of a Witch |

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West is an American novel published in 1995, written by Gregory Maguire with illustrations by Douglas Smith. It is the first in The Wicked Years series, and was followed by Son of a Witch (published in September 2005), A Lion Among Men (published in October 2008), and Out of Oz (published in November 2011).

Wicked is a revisionist exploration of the characters and setting of the 1900 novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum, its sequels, and the 1939 film adaptation. It is presented as a biography of the Wicked Witch of the West, here given the name "Elphaba." The book follows Elphaba from her birth as the result of rape through her radicalization, social ostracism, and finally her death at the hands of Dorothy Gale. Maguire shows the traditionally villainous character in a sympathetic light, using her journey to explore the problem of evil and the "nature versus nurture" debate, as well as themes of terrorism, propaganda, and life purpose.

In 2003, it was adapted as the Tony Award-winning Broadway musical Wicked. The musical has been adapted into a two-part feature film, with the first film released in November 2024 and the second film expected in November 2025.

Background

[edit]Maguire began contemplating the nature of evil while living in London in the early 1990s. He noticed that while the problem of evil had been explored from many different perspectives, those perspectives were seldom synthesized together.[1] He wondered whether calling a person evil might be enough to cause a self-fulfilling prophecy.

If everyone was always calling you a bad name, how much of that would you internalize? How much of that would you say, all right, go ahead, I'll be everything that you call me because I have no capacity to change your minds anyway so why bother. By whose standards should I live?[2]

He was also inspired by the 1993 murder of James Bulger, in which both victim and perpetrators were young children.

Everyone was asking: how could those boys be so villainous? Were they born evil or were there circumstances that pushed them towards behaving like that? It propelled me back to the question of evil that bedevils anybody raised Catholic.[3]

Up to that point strictly a children's author, Maguire had difficulty finding an effective way to write about evil, since in his mind, there were no truly evil characters in children's literature. In what he later described as "the one great revelation of my life," Maguire realized that there were in fact villains in children's books; however, they were usually written as one-dimensional stock characters in order to provoke a quick emotional reaction from young readers. Wondering whom to write about, he envisioned the Wicked Witch of the West, as played by Margaret Hamilton in the MGM film, delivering her iconic line, "I'll get you, my pretty, and your little dog too!"[4] Maguire had a lifelong fascination with The Wizard of Oz, both Baum's original novel and the film, which he watched every year during its annual broadcast.[1][5] He decided to tell the Wicked Witch's life story using the same large scale and broad moral messages found in the novels of Charles Dickens.[3]

Plot

[edit]In the Land of Oz, a minister's wife, Melena Thropp, gives birth to a daughter, Elphaba. Elphaba has green skin, sharp teeth, a savage demeanor, and a fear of water. The story details Elphaba's difficult childhood before flashing forward to show her at Shiz University with her social climbing roommate Galinda, who is destined to become Glinda.

While at Shiz, the two girls discover that Oz is rife with political tension. Headmistress and Ozian power broker Madame Morrible suggests that Elphaba and Glinda work for her from behind the scenes to help stabilize the political situation in Oz. Preferring more direct action, Elphaba and Glinda travel to the Emerald City, where they meet the Wizard and plead their case. When the Wizard dismisses their concerns, Elphaba takes matters into her own hands. She goes into hiding and joins an underground terrorist group working out of the Emerald City.

Five years later, Elphaba reconnects with former schoolmate Prince Fiyero, now married with three children, and the two begin an illicit affair. Fiyero is caught in Elphaba's hideout and arrested by the Wizard's secret police force. Blaming herself for his capture, Elphaba takes refuge in a convent. Seven years later, she visits Fiyero's family at their castle, Kiamo Ko, in hopes of gaining their forgiveness. She brings along a boy named Liir, her son by Fiyero. Fiyero's family allow her to stay as their guest, but his wife Sarima refuses to hear her apology. While there, Elphaba begins to study sorcery and gains a reputation as a witch.

Elphaba's father asks for her help with her sister Nessarose, who has also become a witch and has taken Elphaba's hereditary position as ruler of Munchkinland. Tired of being used as a pawn in other people's agendas and having no interest in ruling, Elphaba instead renounces her claim. Nessarose promises to give Elphaba her enchanted silver shoes after she dies. When Elphaba returns to Kiamo Ko, she discovers the Wizard's troops have taken Fiyero's family prisoner.

Seven years later, a storm visits Munchkinland, dropping a farmhouse on Nessarose and killing her. The farmhouse's passengers are a little girl named Dorothy Gale and her little dog, Toto. Elphaba and Glinda reunite for the first time in years shortly after Nessarose's death. Upon learning Glinda sent Dorothy off with Nessarose's shoes, for fear of their power igniting a civil war in Munchkinland, Elphaba is furious, as the shoes were rightfully hers.

Elphaba meets with the Wizard to beg for the release of Fiyero and his family. The Wizard explains that he has killed them all except for Fiyero's daughter Nor, whom he keeps as a slave. He explains that he comes from a different world and is not bound by the laws of Oz. After the unsuccessful meeting, Elphaba learns from the Time Dragon Clock that the Wizard is her biological father, making her the child of two different worlds and thus destined never to fit in anywhere.

When Dorothy and her friends arrive at Kiamo Ko, she tells Elphaba that while the Wizard sent her with orders to "kill the Wicked Witch of the West," Dorothy came to apologize for killing Nessarose. Furious that Dorothy is asking for the forgiveness she herself has been denied, Elphaba waves her burning broom in the air and inadvertently sets her skirt on fire. Dorothy throws a bucket of water on her to save her. Instead, the water (fatal to witches) melts her away.

Dorothy returns to the Wizard with a green bottle, which he recognizes as the potion he used to drug Melena years earlier. He hastily departs the Emerald City for his own world mere hours before a coup would have overthrown and killed him. The book ends with political chaos reigning over Oz.

Major characters

[edit]- Elphaba Thropp: The protagonist of the book, Elphaba is a green-skinned girl who later becomes known as the Wicked Witch of the West. Later in the book, it is revealed that she is the daughter of the Wizard. The Wicked Witch of the West is not given a name in Baum's novels; Maguire derived the name Elphaba from Baum's initials, LFB.[3]

- Galinda Arduenna Upland (later Glinda): Elphaba's roommate at Shiz University, who eventually becomes the Good Witch of the South. She hates Elphaba at first, but they later become close friends.

- Nessarose Thropp: Elphaba's younger sister, who eventually becomes known as "the Wicked Witch of the East." Nessarose was born without arms, but is extremely beautiful, causing Elphaba to resent her.

- Fiyero Tigelaar: The prince of the Arjiki tribe, in the Vinkus. He meets Elphaba at Shiz and later has an affair with her while she is involved in the resistance movement against the Wizard of Oz.

- The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: The book's main antagonist. The Wizard is a human who came to Oz from Earth in a hot air balloon. He was originally seeking the Grimmerie, but discovered he could orchestrate a coup d'état and take power for himself.

- Madame Morrible: Headmistress of Shiz University's Crage Hall, which Elphaba and Galinda attend, and a behind-the-scenes power broker in Ozian politics.

- Dr. Dillamond: Elphaba's mentor and favorite professor at Shiz. A Goat who is later assassinated as part of the Wizard's campaign against sentient Animals.

- Melena Thropp: The mother of Elphaba, Nessarose, and their brother Shell.

- Frexspar: Melena's husband, a traveling minister.

Themes

[edit]Nature of evil

[edit]According to author Maguire, Wicked is primarily about identifying with someone who is ostracized.[3] The Gazette called Wicked "a cautionary tale...about what happens when we as a society decide to label anyone who differs from the norm as evil."[6]

Prior to writing Wicked, Maguire became interested in examining the nature of evil from the perspective of someone considered evil.[1] He noted that while Baum had deliberately avoided using traditional fairy tale characters in writing the original novel, the Wicked Witch of the West was the sole exception, being depicted as the stereotypical "witch in her castle" figure, with wickedness her single defining character trait.[7] The novel raises the question of whether evil is inborn or acquired. Elphaba is a social outcast despite being of noble birth, which makes her question how much power she truly has over her own life.[8]

Propaganda and terrorism

[edit]Writing for The American Experience, Rebecca Onion called Wicked "an extended meditation on power and politics."[9] Maguire has noted the similarities between the words "wicked" and "Hitler," calling it "no accident" that he chose this title for his book. He recalled reading a newspaper headline in 1991 comparing Saddam Hussein to Adolf Hitler and feeling firsthand the emotional power of propaganda.[6] Maguire "set out to examine the language and propaganda used to marshal brute force against individuals or minorities that might have been opposed to the war."[10] In the book, one major plank of the Wizard's agenda involves the subjugation of sentient Animals[8] and Madame Morrible promotes this idea using a type of moralistic poem called a "quell." Elphaba instantly sees the propaganda for what it is.[11]

Tor noted that terrorism, committed both by and against the state, plays a major role in the second half of the book. The Wizard keeps an SS-like secret police, the Gale Force, which uses violence to carry out his totalitarian agenda. Elphaba similarly uses terrorism to combat them,[9] though she shies away from targeting children.[8]

Life purpose

[edit]A lifelong Catholic, Maguire remembered the nuns who taught in the Catholic schools of his boyhood home of Albany, New York. He admired their sense of purpose and dedication to their cause, saying that their integrity and inscrutability made them witches in his mind.[12] Elphaba discovers her own purpose as a student at Shiz University, where the murder of her favorite professor, Dr. Dillamond, inspires her to join the cause of Animal rights.[13] As the story progresses, she deepens her commitment to her cause, becoming a political exile for her beliefs.[8][14]

As revisionist literature

[edit]Wicked is on its face a revisionist parallel novel for The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. The Independent compared it to Wide Sargasso Sea and Wild Wood as part of "a fascinating sub-genre of novels that revisit well-known stories as much in the spirit of criticism as homage."[14] While previous authors had accepted the existing moral framework of the Oz stories, Wicked showed affection for the originals while simultaneously questioning everything they stood for. Maguire presents a sympathetic view of a villainous character by detailing her life story and helping the reader understand how "an innocent if rather green and biting child" can become "a still moralistic terrorist."[8] He also transformed the Land of Oz itself, changing what he saw as an insular, parochial world into one where different groups and their political agendas intersect and overlap.[9]

Reception

[edit]Wicked received mostly positive reviews. Publishers Weekly called it a "fantastical meditation on good and evil, God and free will" which combined "puckish humor and bracing pessimism."[15] Kirkus Reviews called it "A captivating, funny, and perceptive look at destiny, personal responsibility, and the not-always-clashing beliefs of faith and magic." Library Journal recommended the book to "good readers who like satire, and love exceedingly imaginative and clever fantasy." The Los Angeles Times favorably compared Wicked with other "fantasy novels of ideas" such as Gormenghast and Dune.[16]

The New York Times was a notable outlier, criticizing the novel's strident politics and moral relativism. Reviewer Michiko Kakutani argued that Maguire "shows little respect for Baum's original story." Wicked, she felt, "turns a wonderfully spontaneous world of fantasy into a lugubrious allegorical realm, in which everything and everyone is labeled with a topical name tag."[13]

Adaptations

[edit]Musical

[edit]In 2003, the novel was adapted as the Broadway musical Wicked by composer/lyricist Stephen Schwartz and librettist Winnie Holzman. The musical was produced by Universal Pictures and directed by Joe Mantello, with musical staging by Wayne Cilento. The Broadway production was followed by long-running productions in Chicago, London, San Francisco, and Los Angeles in the United States, as well as Germany and Japan. It was nominated for ten Tony Awards, winning three, and is the 4th longest-running Broadway show in history, with over 7,400 performances. The original Broadway production starred Idina Menzel as Elphaba and Kristin Chenoweth as Glinda.[17]

Unproduced television program

[edit]In a 2009 interview, Maguire stated that he had sold the rights to ABC to make an independent non-musical TV adaptation of Wicked. It would not be based on Winnie Holzman's script.[18] On January 9, 2011, Entertainment Weekly reported that ABC would be teaming up with Salma Hayek and her production company to create a TV miniseries of Wicked based solely on Maguire's novel.[19] The miniseries never entered production.

Films

[edit]In September 2010, Filmshaft disclosed that Universal Pictures was beginning work on a film adaptation of the stage musical.[20] In December 2012, following the success of Les Misérables,[21][22] Marc Platt, also a producer of the stage version, announced the film was going ahead,[23] later confirming the film was aiming for a 2016 release.[24] Universal announced in 2016 that the film would be released in theaters on December 22, 2021, with Stephen Daldry directing.[25] After production was shut down during the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic,[26] Daldry left the production due to scheduling conflicts[27] and was replaced by Jon M. Chu.[26] Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande were cast as Elphaba and Galinda, respectively, with rehearsals set to begin in July 2022.[28] Michelle Yeoh was announced for the Madame Morrible role in December 2022.[29]

In April 2022, it was announced that the film will be released in two parts, with the first one released on November 22, 2024 and the second part to be released on November 26, 2025.[30]

Graphic novel

[edit]In March 2025, William Morrow Paperbacks will publish the first volume of a graphic novel adaptation of Wicked, with illustrations by Scott Hampton.[31]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Jung, Kang-hyun (June 28, 2012). "The story behind 'Wicked's' Gregory Maguire". Korea JoongAng Daily. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ Wilson, Jacque (November 4, 2008). "'Wicked' author Gregory Maguire returns to Oz". CNN. Archived from the original on June 12, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Wiegand, Chris (September 27, 2021). "'They changed my ending, I felt aghast': how we made Wicked". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ Rabinowitz, Chloe. "BWW Interview: Gregory Maguire Talks 25th Anniversary Edition of the WICKED Novel, Dream Casts the WICKED Movie and More". BroadwayWorld.com. Archived from the original on 2021-03-04. Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ^ DeWitt, Peter (2012-05-31). "A Wicked Good Interview with Gregory Maguire". Education Week. ISSN 0277-4232. Archived from the original on 2022-03-21. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ a b Moore, John (23 October 2021). "The meaning of 'Wicked' won't go away". Colorado Springs Gazette. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ "Wizard's Wireless: Interviews With Artists Inspired by Oz". www.frodelius.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-24. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ^ a b c d e Ness, Mari (2010-12-16). "Responding to Fairyland: Gregory Maguire's Wicked". Tor.com. Archived from the original on 2022-03-21. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ a b c Onion, Rebecca (April 21, 2021). "Why Is the Wizard of Oz So Wonderful?". American Experience. PBS. Archived from the original on March 22, 2022. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ Usher, Robin (March 1, 2008). "Those Wicked ways". The Age. Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ^ Maguire, Gregory (1995). Wicked : the life and times of the wicked witch of the West : a novel (1st ed.). New York: ReganBooks. pp. 83–85. ISBN 0-06-039144-8.

- ^ Rizzo, Frank (October 30, 2014). "The Evolution Of 'Wicked' From 'Oz'". Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on July 13, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ a b "BOOKS OF THE TIMES;Let's Get This Straight: Glinda Was the Bad One? - The New York Times". The New York Times. 2021-02-11. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ a b "Wicked, by Gregory Maguire". The Independent. 2006-03-08. Archived from the original on 2022-03-21. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ "Fiction Book Review: Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West by Gregory Maguire, Author, Douglas Smith, Illustrator William Morrow & Company $26.99 (416p) ISBN 978-0-06-039144-7". PublishersWeekly.com. Archived from the original on 2022-03-21. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ BookBrowse. "Summary and reviews of Wicked by Gregory Maguire". BookBrowse.com. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ "Wicked – Broadway Musical – Original | IBDB". www.ibdb.com. Archived from the original on 2021-01-27. Retrieved 2022-04-07.

- ^ Milvy, Erika (February 27, 2009). "Gregory Maguire on Wickedness Post-Bush". 7x7. 7x7 Bay Area, Inc. Archived from the original on January 3, 2010. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ^ Lyons, Margaret (January 9, 2011). "ABC, Salma Hayek developing 'Wicked' miniseries". Entertainment Weekly. Meredith Corporation. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2011.

- ^ Sharp, Jamie (September 6, 2010). "Finally – Wicked: The Movie This Way Comes!". FilmShaft. Archived from the original on January 3, 2011. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ Belloni, Matthew (February 20, 2013). "Universal Chairman Wants 'Fifty Shades' for Summer 2014, More 'Bourne' and 'Van Helsing' Reboot (Q&A)". The Hollywood Reporter. Billboard-Hollywood Reporter Media Group. Archived from the original on February 23, 2013. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ^ Cerasaro, Pat (February 21, 2013). "LES MISERABLES Hit Status Leading To WICKED Movie At Universal?". BroadwayWorld. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ^ "WICKED Film to Enter Development 'Soon'". BroadwayWorld. December 13, 2012. Archived from the original on December 16, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ^ Madison, Charles (December 1, 2014). "Wicked movie finally seems to be on course, set for 2016 release". Film Divider. Archived from the original on January 17, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (June 16, 2016). "Universal's 'Wicked' Movie Adaptation Gets December 2019 Release". The Hollywood Reporter. Billboard-Hollywood Reporter Media Group. Archived from the original on September 1, 2016. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Galuppo, Mia (February 2, 2021). "Jon M. Chu Set to Direct 'Wicked' Musical". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (October 20, 2020). "'Wicked' Director Stephen Daldry Exits Universal Movie Musical Adaptation". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Gibson, Kelsie (March 1, 2022). "Everything to Know About the Wicked Movie Starring Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande". People. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ Malkin, Marc (2022-12-08). "Michelle Yeoh to Star in 'Wicked' Movies as Madame Morrible (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved 2022-12-15.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (April 26, 2022). "Universal Releasing 'Wicked' Musical In Two Parts". Deadline. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Maguire, Gregory (March 11, 2025). "Wicked: The Graphic Novel Part I". WIlliam Morrow Paperbacks.