William Styron

William Styron | |

|---|---|

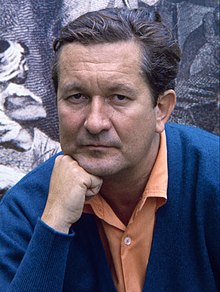

William Styron, 1967 | |

| Born | William Clark Styron Jr. June 11, 1925 Newport News, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | November 1, 2006 (aged 81) Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Occupation | Novelist, essayist |

| Education | Davidson College Duke University (BA) |

| Period | 1951–2006 |

| Notable works | Lie Down in Darkness The Confessions of Nat Turner Sophie's Choice Darkness Visible |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 4, including Alexandra |

| Signature | |

| |

| Website | |

| william-styron | |

William Clark Styron Jr. (June 11, 1925 – November 1, 2006) was an American novelist and essayist who won major literary awards for his work.[1]

Early life

[edit]Styron was born in the Hilton Village historic district[2] of Newport News, Virginia, the son of Pauline Margaret (Abraham) and William Clark Styron.[1] His birthplace was less than a hundred miles from the site of Nat Turner's slave rebellion, the inspiration for Styron's most famous and controversial novel.

Styron's mother was from the North while his father was a Southern liberal, laying out broad racial perspectives in the household. Styron's father, a shipyard engineer, suffered clinical depression, as would later Styron himself. In 1939, at age 14, Styron lost his mother after her decade-long battle with breast cancer.

Styron attended public school in Warwick County, first at Hilton School and then at Morrison High School (now known as Warwick High School) for two years, until his father sent him to Christchurch School, an Episcopal college-preparatory school in the Tidewater region of Virginia. Styron once said "of all the schools I attended ... only Christchurch ever commanded something more than mere respect—which is to say, my true and abiding affection."[3]

On graduation, Styron enrolled in Davidson College[4] and joined Phi Delta Theta. By age eighteen he was reading the writers who would have a lasting influence on his own work, especially Thomas Wolfe.[4] Styron transferred to Duke University in 1943 as a part of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps V-12 program aimed at fast-tracking officer candidates by enrolling them simultaneously in basic training and bachelor's degree programs. There he published his first fiction, a short story heavily influenced by William Faulkner, in an anthology of student work [citation needed]. Styron published several short stories in the university literary magazine, The Archive, between 1944 and 1946.[5] Though Styron was made a lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps, the Japanese surrendered before his ship left San Francisco. After the war, he returned to full-time studies at Duke and completed his Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) in English in 1947.[5]

Career

[edit]After graduation, Styron took an editing position with McGraw-Hill in New York City. Styron later recalled the misery of this work in an autobiographical passage of Sophie’s Choice. After provoking his employers into firing him, he set about writing his first novel in earnest. Three years later, he published the novel, Lie Down in Darkness (1951), the story of a dysfunctional Virginia family. The novel received overwhelming critical acclaim. For this novel, Styron received the Rome Prize, awarded by the American Academy in Rome and the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Military service

[edit]His recall into the military due to the Korean War prevented him from immediately accepting the Rome Prize. Styron joined the Marine Corps, but was discharged in 1952 for eye problems. However, he was to transform his experience at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina into his short novel, The Long March, published serially the following year. This was adapted for the Playhouse 90 episode "The Long March" in 1958.

Travels in Europe

[edit]Styron spent an extended period in Europe. In Paris, he became friends with writers Romain Gary, George Plimpton, Peter Matthiessen, James Baldwin, James Jones and Irwin Shaw, among others. In 1953, the group founded the magazine The Paris Review, which became a celebrated literary journal.[4]

The year 1953 was eventful for Styron in another way. Finally able to take advantage of his Rome Prize, he traveled to Italy, where he became friends with Truman Capote. At the American Academy, he renewed an acquaintance with a young Baltimore poet, Rose Burgunder, to whom he had been introduced the previous fall at Johns Hopkins University. They were married in Rome in the spring of 1953.

Some of Styron's experiences during this period inspired his third published book Set This House on Fire (1960), a novel about intellectual American expatriates on the Amalfi coast of Italy. The novel received mixed reviews in the United States, although its publisher considered it successful in terms of sales. In Europe its translation into French achieved best-seller status, far outselling the American edition.

Nat Turner controversy

[edit]Styron's next two novels, published between 1967 and 1979, sparked much controversy. Feeling wounded by his first truly harsh reviews[6] for Set This House on Fire, Styron spent the years after its publication researching and writing his next novel, the fictitious memoirs of the historical Nathaniel "Nat" Turner, a slave who led a slave rebellion in 1831.

During the 1960s, Styron became an eyewitness to another time of rebellion in the United States, living and writing at the heart of that turbulent decade, a time highlighted by the counterculture revolution with its political struggle, civil unrest, and racial tension. The public response to this social upheaval was furious and intense: battle lines were being drawn. In 1968, Styron signed the "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" pledge, a vow refusing to pay taxes as a protest against the Vietnam War.[7]

In this atmosphere of dissent, many[who?] had criticized Styron's friend James Baldwin for his novel Another Country, published in 1962. Among the criticisms was outrage over a black author choosing a white woman as the protagonist in a story that tells of her involvement with a black man. Baldwin was Styron's house guest for several months following the critical storm generated by Another Country. During that time, he read early drafts of Styron's new novel, and predicted that Styron's book would face even harsher scrutiny than Another Country. "Bill's going to catch it from both sides", he told an interviewer immediately following the 1967 publication of The Confessions of Nat Turner.

Baldwin's prediction was correct, and despite public defenses of Styron by leading artists of the time, including Baldwin and Ralph Ellison, numerous other black critics reviled Styron's portrayal of Turner as racist stereotyping. The historian and critic John Henrik Clarke edited and contributed to a polemical anthology, William Styron's Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond, published in 1968 by Beacon Press. Particularly controversial was a passage in which Turner fantasizes about raping a white woman. Several critics pointed to this as a dangerous perpetuation of a traditional Southern justification for lynching. Styron also writes of a situation where Turner and another slave boy have a homosexual encounter while alone in the woods. Despite the controversy, the novel was a runaway critical and financial success, and won both the 1968 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction[8] and the William Dean Howells Medal in 1970.

Benjamin Reid controversy

[edit]In the early 1960s, Styron became a mentor to prisoner Benjamin Reid, who in 1957 had beaten a woman to death with a hammer in a botched robbery attempt. Through his writings and advocacy, Styron successfully helped to have Reid's death sentence commuted in 1962. In 1970, Reid escaped prison before his scheduled parole and kidnapped and raped a woman.[9]

Sophie's Choice

[edit]Styron's next novel, Sophie's Choice (1979), also generated significant controversy, in part due to Styron's decision to portray a non-Jewish victim of Nazism and in part due to its explicit sexuality and profanity. It was banned in South Africa, censored in the Soviet Union, and banned in Poland for "its unflinching portrait of Polish anti-Semitism."[10] It has also been banned in some high schools in the United States.[11]

The novel tells the story of Sophie (a Polish Roman Catholic who survived Auschwitz), Nathan (her brilliant Jewish lover who had paranoid schizophrenia), and Stingo (a Southern transplant in post-World War II-Brooklyn who was in love with Sophie). It won the 1980 National Book Award[12][n 1] and was a nationwide bestseller. A 1982 film version was nominated for five Academy Awards, with Meryl Streep winning the Academy Award for Best Actress for her portrayal of Sophie. Kevin Kline and Peter MacNicol played Nathan and Stingo, respectively.

Darkness Visible

[edit]Styron's readership expanded with the publication of Darkness Visible in 1990. This memoir, which began as a magazine article, chronicles the author's descent into depression and his near-fatal night of "despair beyond despair".[13] It is a first-hand account of a major depressive episode and challenged the modern taboo on acknowledging such issues. The memoir's goals included increasing knowledge and decreasing stigmatization of major depressive disorders and suicide. It explored the phenomenology of the disease among those with depression, their loved ones, and the general public as well.

Earlier, in December 1989, Styron had written an op-ed for The New York Times responding to the disappointment and mystification among scholars about the apparent suicide of Primo Levi, the remarkable Italian writer who survived the Nazi death camps, but apparently had depression in his final years. Reportedly, it was the public's unsympathetic response to Levi's death that impelled Styron to take a more active role as an advocate for educating the public about the nature of depression and the role it played in mental health and suicide.[4]

Styron noted in an article for Vanity Fair that

the pain of severe depression is quite unimaginable to those who have not suffered it, and it kills in many instances because its anguish can no longer be borne. The prevention of many suicides will continue to be hindered until there is a general awareness of the nature of this pain. Through the healing process of time—and through medical intervention or hospitalization in many cases—most people survive depression, which may be its only blessing; but to the tragic legion who are compelled to destroy themselves there should be no more reproof attached than to the victims of terminal cancer.[14]

Later work and acclaim

[edit]

Styron was awarded the St. Louis Literary Award from the Saint Louis University Library Associates.[15][16]

Styron was awarded the Prix mondial Cino Del Duca in 1985.

His short story "Shadrach" was filmed in 1998, under the same title. It was co-directed by his daughter Susanna Styron.

Other works published during his lifetime include the play In the Clap Shack (1973), and a collection of his nonfiction, This Quiet Dust (1982).

French president François Mitterrand invited Styron to his first Presidential inauguration, and later made him a Commander of the Legion of Honor.[17] In 1993, Styron was awarded the National Medal of Arts.[18]

In 2002 an opera by Nicholas Maw based on Sophie's Choice premièred at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, London. Maw wrote the libretto and composed the music. He had approached Styron about writing the libretto, but Styron declined. Later the opera received a new production by stage director Markus Bothe at the Deutsche Oper Berlin and the Volksoper Wien, and had its North American premiere at the Washington National Opera in October 2006.[19]

A collection of Styron's papers and records is housed at the Rubenstein Library, Duke University.[5]

In 1996 William Styron received the 1st Fitzgerald Award on the centenary of F. Scott Fitzgerald's birth. The F. Scott Fitzgerald Award for Achievement in American Literature award is given annually in Rockville Maryland, the city where Fitzgerald, his wife, and his daughter are buried, as part of the F. Scott Fitzgerald Literary Festival. In 1988 he was awarded the Edward MacDowell Medal.[20]

He was a Charter member of the Fellowship of Southern Writers.

Port Warwick street names

[edit]The Port Warwick neighborhood of Newport News, Virginia, was named after the fictional city in Styron's Lie Down in Darkness. The neighborhood describes itself as a "mixed-use new urbanism development." The most prominent feature of Port Warwick is William Styron Square along with its two main boulevards, Loftis Boulevard and Nat Turner Boulevard, named after characters in Styron's novels. Styron himself was appointed to design a naming system for Port Warwick, deciding to "honor great American writers", resulting in Philip Roth Street, Thomas Wolfe Street, Flannery O'Connor Street, Herman Melville Avenue and others.[21]

Personal life and death

[edit]In 1985, he had his first serious bout with depression. Once he recovered from his illness, Styron was able to write the memoir Darkness Visible (1990), the work for which he became best known during the last two decades of his life.

While doing a fellowship at the American Academy in Rome, Styron renewed a passing acquaintance with young Baltimore poet Rose Burgunder. They married in Rome in the spring of 1953. Together, they had four children: daughter Susanna Styron is a film director; daughter Paola is an internationally acclaimed modern dancer; daughter Alexandra is a writer, known for the 2001 novel All The Finest Girls and 2011 memoir Reading My Father: A Memoir; son Thomas is a professor of clinical psychology at Yale University.

Styron died from pneumonia on November 1, 2006, at age 81, on Martha's Vineyard. He is buried at West Chop Cemetery in Vineyard Haven, Dukes County, Massachusetts.[22]

Bibliography

[edit]Note – the following is a list of the first American editions of Styron's books

- Lie Down in Darkness. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1951.

- The Long March. New York: Random House, 1956.[n 2]

- Set This House on Fire. New York: Random House, 1960

- The Confessions of Nat Turner. New York: Random House, 1967.

- In the Clap Shack. New York: Random House, 1973.

- Sophie's Choice. New York: Random House, 1979.

- Shadrach. Los Angeles: Sylvester & Orphanos, 1979.

- This Quiet Dust and Other Writings. New York: Random House, 1982. Expanded edition, New York: Vintage, 1993.

- Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness. New York: Random House, 1990.

- A Tidewater Morning: Three Tales from Youth. New York: Random House, 1993

- Inheritance of Night: Early Drafts of Lie Down in Darkness. Preface by William Styron. Ed. James L. W. West III. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1993.

- Havanas in Camelot: Personal Essays. New York: Random House, 2008.

- The Suicide Run: Fives Tales of the Marine Corps. New York: Random House, 2009.

- Selected Letters of William Styron. Edited by Rose Styron, with R. Blakeslee Gilpin. New York: Random House, 2012.

- My Generation: Collected Nonfiction. Edited by James L.W. I West III. New York: Random House, 2015.

Notes

[edit]- ^ This was the 1980 award for hardcover general Fiction.

From 1980 to 1983 in National Book Awards history there were dual hardcover and paperback awards in most categories, and multiple fiction categories, especially in 1980. Most of the paperback award-winners were reprints, including the 1980 general Fiction. - ^ 1952 (serial), 1956 (book)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher (November 2, 2006). "William Styron, Novelist, Dies at 81". The New York Times. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ "THE RETURN OF A VILLAGE HISTON'S BOOSTERS SEE POTENTIAL IN ITS QUAINT WWI STRUCTURES". scholar.lib.vt.edu.

- ^ "Daily Press: Hampton Roads News, Virginia News & Videos". Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Homberger, Eric (November 3, 2006). "Obituary: William Styron". The Guardian. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c "William Styron Papers, 1855–2007 and undated". Rubenstein Library, Duke University.

- ^ "Timeline │ The Official Webpage about American Author William Styron". William-Styron.com. August 25, 2018.

- ^ "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" January 30, 1968 New York Post

- ^ Confessions of Nat Turner, Amazon.com

- ^ Sullivan, Patricia (November 1, 2006). "William Styron; Noted Author of 'Nat Turner,' 'Sophie's Choice'". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on September 9, 2024. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ Sirlin, Rhoda and West III, James L. W. Sophie's Choice: A Contemporary Casebook. Newcastle UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007. p. ix. http://www.cambridgescholars.com/download/sample/60485 Archived July 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed January 5, 2013.

- ^ Helfand, Duke. "Students Fight for 'Sophie's Choice" Los Angeles Times. December 22, 2001. Accessed January 5, 2013.

- ^ "National Book Awards – 1980". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

With essay by Robert Weil from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog. - ^ Kakutani, Michiko (November 3, 2006). "Styron Visible: Naming the Evils That Humans Do". The New York Times. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ Styron, William (December 1989). "Darkness Visible". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ^ "Website of St. Louis Literary Award". Archived from the original on August 23, 2016. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ Saint Louis University Library Associates. "Recipients of the Saint Louis Literary Award". Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ "William Styron, Pulitzer Prize-Winning Author". ShopHiltonVillage.com. Archived from the original on June 2, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ^ "Lifetime Honors – National Medal of Arts". Nea.gov. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ^ Kozinn, Allan (May 19, 2009). "Nicholas Maw, British Composer, Is Dead at 73". The New York Times. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

- ^ "MacDowell Medal winners — 1960–2011". The Telegraph. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "William Styron". Portwarwick.com. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Literature. University of North Carolina Press. 2006. p. 438. ISBN 978-0-8078-3190-8.

External links and further reading

[edit]- Peter Matthiessen and George Plimpton (Spring 1954). "William Styron, The Art of Fiction No. 5". The Paris Review. Spring 1954 (5).

- George Plimpton (Spring 1999). "William Styron, The Art of Fiction No. 156". The Paris Review. Spring 1999 (150).

- James Campbell, "Tidewater traumas", The Guardian Unlimited website

- William Styron at IMDb

- Kenneth S. Greenberg, ed. Nat Turner: A Slave Rebellion in History and Memory, New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. xix + 289 pp., ISBN 978-0-19-513404-9 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-19-517756-5 (paper).

- James L. W. West III [editor], Conversations with William Styron, Jackson, MS: University of Mississippi Press, 1985. ISBN 0-87805-260-7.

- James L. W. West III, William Styron: A Life, New York: Random House, 1998. ISBN 0-679-41054-6

- Charlie Rose with William Styron, A discussion about mental illness, 50-minute interview

- William Styron interview with William Waterway Marks on "The Vineyard Voice"/1989/covers a range of topics.

- "An Appreciation of William Styron", Charlie Rose, – 55-minute-long video

- A Conversation with William Styron Archived September 7, 2015, at the Wayback Machine on-line reprint of interview published in Humanities, 18,3 (1997),

- William Styron interview on Martha's Vineyard, William Styron interview by author and TV host William Waterway Marks with rare photo of Styron sitting at desk in his island writing studio.

- Michael Lackey, "The Theology of Nazi Anti-Semitism in William Styron's Sophie's Choice," Lit: Literature Interpretation Theory, 22,4 (2011), 277–300.

- KCRW Bookworm Interview

- A memoir of life with Styron by his writer daughter, Alexandra Styron.

- Stuart Wright Collection: William Styron Papers (#1169-011), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University

- William Styron: An Author's Life and Career, a comprehensive website maintained by James L. W. West III, Styron's biographer.

- 1925 births

- 2006 deaths

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American novelists

- American male novelists

- American tax resisters

- American writers about the Holocaust

- Deaths from pneumonia in Massachusetts

- Duke University Trinity College of Arts and Sciences alumni

- Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- Military personnel from Virginia

- National Book Award winners

- Novelists from Virginia

- People from Newport News, Virginia

- People from Tisbury, Massachusetts

- People with mood disorders

- Pulitzer Prize for Fiction winners

- United States Marine Corps officers

- United States Marine Corps personnel of World War II

- United States Marine Corps personnel of the Korean War

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients