Aliens (film)

| Aliens | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | James Cameron |

| Screenplay by | James Cameron |

| Story by |

|

| Based on | |

| Produced by | Gale Anne Hurd |

| Starring | Sigourney Weaver |

| Cinematography | Adrian Biddle |

| Edited by | Ray Lovejoy |

| Music by | James Horner |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 137 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $18.5 million |

| Box office | $131.1–183.3 million |

Aliens is a 1986 science fiction action film written and directed by James Cameron. It is the sequel to the 1979 science fiction horror film Alien, and the second film in the Alien franchise. Set in the far future, it stars Sigourney Weaver as Ellen Ripley, the sole survivor of an alien attack on her ship. When communications are lost with a human colony on the moon where her crew first encountered the alien creatures, Ripley agrees to return to the site with a unit of Colonial Marines to investigate. Michael Biehn, Paul Reiser, Lance Henriksen, and Carrie Henn are featured in supporting roles.

Despite the success of Alien, its sequel took years to develop due to lawsuits, a lack of enthusiasm from 20th Century Fox, and repeated management changes. Although relatively inexperienced, Cameron was hired to write a story for Aliens in 1983 on the strength of his scripts for The Terminator (1984) and Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985). The project stalled again until new Fox executive Lawrence Gordon pursued a sequel. On an approximately $18.5 million budget, Aliens began principal photography in September 1985 and concluded in January 1986. The film's development was tumultuous and rife with conflicts between Cameron and the British crew at Pinewood Studios. The difficult shoot affected the composer, James Horner, who was given little time to record the music.

Aliens was released on July 18, 1986, to critical acclaim. Reviewers praised its action, but some criticized the intensity of some scenes. Weaver's performance garnered consistent praise along with those of Bill Paxton and Jenette Goldstein. The film received several awards and nominations, including an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress for Weaver at a time when the science-fiction genre was generally overlooked. It earned $131.1–183.3 million during its theatrical run, making it one of the highest-grossing films of 1986 worldwide.

Aliens is now considered among the greatest films of the 1980s, and among the best science fiction, action, and sequel films ever made, arguably equal to or better than Alien.[a] It is credited with expanding the franchise's scope with additions to the series' backstory and factions such as the Colonial Marines. It inspired a variety of merchandise, including video games, comic books and toys. It was followed by two sequels: Alien 3 (1992) and Alien Resurrection (1997).

Plot

[edit]Ellen Ripley has been in stasis for 57 years aboard an escape shuttle after destroying her ship, the Nostromo, to escape an alien creature that slaughtered the rest of the crew.[i] She is rescued and debriefed by her employers at the Weyland-Yutani Corporation, who are skeptical of her claim about alien eggs in a derelict ship on the exomoon LV-426,[ii] now the site of a terraforming colony.

After contact is lost with the colony, Weyland-Yutani representative Carter Burke and Colonial Marine Lieutenant Gorman ask Ripley to accompany them to investigate. Still traumatized by her alien encounter, she agrees on the condition that they exterminate the creatures. Ripley is introduced to the Colonial Marines on the spaceship Sulaco but is distrustful of their android, Bishop, because the android aboard the Nostromo had betrayed its crew to protect the alien on company orders.

A dropship delivers the expedition to the surface of LV-426, where they find the battle-ravaged colony and two live alien facehuggers in containment tanks, but no bodies or colonists, except for a traumatized young girl nicknamed Newt. The team locates the colonists beneath the fusion-powered atmosphere processing station and heads to their location, descending into corridors covered in alien secretions. At the station's center, the Marines find opened eggs and dead facehuggers alongside the cocooned colonists, now serving as incubators for the creatures' offspring. The Marines kill an infant alien after it bursts from a colonist's chest, rousing several adult aliens who ambush the Marines, killing or capturing many of them. When the inexperienced Gorman panics, Ripley assumes command, takes control of their armored personnel carrier, and rams the nest to rescue Corporal Dwayne Hicks and Privates Hudson and Vasquez. Hicks orders the dropship to recover the survivors, but a stowaway alien kills the pilots, causing the dropship to crash into the station. Almost out of ammunition and resources, the survivors barricade themselves inside the colony.

Ripley discovers that Burke ordered the colonists to investigate the derelict spaceship containing the alien eggs, intending to profit by recovering them for biological weapon research. Before she can expose him, Bishop informs the group that the dropship crash damaged the power plant's cooling system, and the plant will soon overheat and explode, destroying the colony. He volunteers to travel to the colony transmitter and remotely pilot the Sulaco's remaining dropship to the surface.

After falling asleep in the medical laboratory, Ripley and Newt awaken to find themselves trapped with the two released facehuggers. Ripley triggers a fire alarm to alert the Marines, who rescue them and kill the creatures. She accuses Burke of releasing the facehuggers to implant her and Newt with alien embryos, allowing him to smuggle them through Earth's quarantine. The power is suddenly cut, and aliens attack through the ceiling. In the ensuing firefight, the aliens kill Burke, subdue Hudson, and injure Hicks; the cornered Gorman and Vasquez sacrifice themselves to avoid capture. Newt is separated from Ripley and taken by the creatures. Ripley brings Hicks to Bishop in the second dropship, but she refuses to abandon Newt and arms herself before descending into the processing station hive alone to rescue her. During their escape, they encounter the alien queen surrounded by dozens of eggs, and when one begins to open, Ripley uses her weapons to destroy them all and the queen's ovipositor. Pursued by the enraged queen, Ripley and Newt join Bishop and Hicks on the dropship and escape moments before the station explodes, consuming the colony in a nuclear blast.

Aboard the Sulaco, the group is ambushed by the queen, who stowed away in the dropship's landing gear. The queen tears Bishop in half and advances on Newt, but Ripley fights the creature with an exosuit cargo loader and expels it through an airlock into space while the damaged Bishop keeps Newt safe. Ripley, Newt, Hicks, and Bishop then enter hypersleep for their return trip to Earth.

Cast

[edit]- Sigourney Weaver as Ellen Ripley: The survivor of an alien attack on her ship, the Nostromo[9]

- Michael Biehn as Dwayne Hicks: A corporal in the Colonial Marines[10]

- Paul Reiser as Carter J. Burke: A Weyland-Yutani Corporation representative[10]

- Lance Henriksen as Bishop: An android aboard the Sulaco[11]

- Carrie Henn as Rebecca "Newt" Jorden: A young girl in the colony on LV-426[8]

- Bill Paxton as Hudson: A boastful but panicky Colonial Marine private[12][13]

- William Hope as Gorman: The Marines' inexperienced commanding officer[12][14]

- Ricco Ross as Frost: A private in the Colonial Marines[12]

- Al Matthews as Apone: The Marines' cool-headed Sergeant[15][16]

The Colonial Marine cast includes privates Vasquez (Jenette Goldstein), Drake (Mark Rolston), Spunkmeyer (Daniel Kash),[12] Crowe (Tip Tipping), and Wierzbowski (Trevor Steedman),[1] and corporals Dietrich (Cynthia Dale Scott) and Ferro (Colette Hiller). In addition to the main cast, Aliens features Paul Maxwell as Van Leuwen (a member of the board reviewing Ripley's competence) and Barbara Coles as the cocooned colonist killed when an alien bursts from her chest.[1][17] Carl Toop and Eddie Powell portray alien warriors.[1][18]

Some scenes removed from Aliens's theatrical version were restored in subsequent releases.[19] Additional credits for these scenes include Newt's father, Russ Jorden (Jay Benedict),[20][21] and her mother Anne (Holly de Jong).[22][23] Henn's brother, Christopher, plays her brother Timmy,[24][25] Mac McDonald portrays colony administrator Al Simpson,[26][27] and Weaver's mother, Elizabeth Inglis, makes a cameo appearance as Ripley's elderly daughter Amanda.[28]

Production

[edit]Early development

[edit]The success of Alien (1979) led to immediate discussions of a sequel, but the production company Brandywine Productions struggled to convince 20th Century Fox to make it. Studio president Alan Ladd Jr. was supportive of the project but left Fox to found the Ladd Company, and his replacement, Norman Levy, was concerned about the cost of producing an Alien II.[29][30][31] Brandywine co-founder David Giler said Levy believed a sequel would be a "disaster".[31] Fox executives believed Alien's success was a fluke, and that it had not generated enough profit or audience interest to warrant a sequel.[31] Box-office returns for horror films were also declining.[32] Progress was further slowed when Giler and Brandywine co-founders Walter Hill and Gordon Carroll sued Fox for unpaid profits from Alien. Using Hollywood accounting methods, Fox had declared Alien a financial loss despite its earnings of over $100 million against a $9–$11 million budget. Brandywine's lawsuit was settled by early 1983, the result being that Fox would finance the development of Alien II, but was not required to distribute the film.[31][33]

Levy's eventual replacement, Joe Wizan, was receptive to a sequel, and although other executives remained noncommittal, Giler's development executive, Larry Wilson, began looking for a scriptwriter by mid-1983.[30][31] Wilson came across the script for the in-development science fiction film, The Terminator (1984), written by James Cameron. With Cameron's collaborative scriptwriting efforts alongside Sylvester Stallone on Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985), Wilson was convinced to show the script for The Terminator to Giler, Hill, and Carroll.[34][35] In November 1983, Cameron submitted a 42-page film treatment for Alien II—written in three days—based on Giler and Hill's suggestion of "Ripley and soldiers".[30][31][36] The studio had a mixed reaction, one executive calling it a constant stream of horror without character development.[30][31] Negotiations to sell the sequel rights to Rambo's developers Mario Kassar and Andrew G. Vajna failed and the project stalled again.[31]

Revival

[edit]By July 1984, Lawrence Gordon had replaced Wizan. With few projects in development, Gordon looked at sequels to Fox's existing properties and came across the Alien II treatment; he said he was surprised that no one had pursued it.[31] Production of The Terminator was delayed for nine months because Arnold Schwarzenegger was contractually obligated to film Conan the Destroyer (1984). Cameron used the time to develop his treatment, expanding it to ninety pages.[30][35] He drew ideas from "Mother", one of his story concepts about an alien on a space station involving a power-loader suit.[37] Because of his low expectations for The Terminator, Cameron had spent much of his free time during its production developing and trying out ideas for Alien II.[34][35]

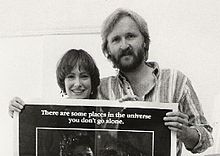

This script was better received by Fox executives and Gordon, but Cameron also wanted to direct the project.[30][35][38] Cameron was a relatively new director, his only directing credit being Piranha II: The Spawning (1982), a low-budget, independent horror film, and the studio was reluctant to grant his request. His credibility was elevated following the surprise financial and critical success of The Terminator in late 1984, and Gordon gave him the job.[31][35][38] Cameron's associates tried to persuade him to reject the offer, believing anything good about the film would be attributed to Alien director Ridley Scott and anything negative to Cameron.[39] Scott said he was never offered the chance to direct the sequel, possibly because he was difficult to work with on the original.[40] The title Aliens reportedly came from Cameron writing "Alien" on a whiteboard during a pitch meeting and adding a "$" suffix.[41][42] Cameron also wanted his collaborative partner and girlfriend, Gale Anne Hurd, to serve as the producer, but Fox did not take the request seriously, believing she could not stand up to Cameron, who believed she was the only person who would.[37][38] Hurd had several industry associates contact Fox executives to convince them she was a legitimate producer.[38]

Cameron turned in the finished script in February 1985, hours before a Hollywood writer's strike.[31] Cameron recalled the audience reactions while seeing Alien in the theater and believed it would be difficult to recreate the emotion and novelty of the original. He and Hurd agreed to combine the horror of Alien with the action of The Terminator. According to Hill, Cameron said if the first film could be compared to a haunted attraction, Aliens should be like a roller coaster.[35] Cameron believed in having a strong female heroine to distinguish his films from typical Hollywood action fare and wrote the script with a picture of Weaver on his desk.[38] He referred to The Terminator, and how he removed the normal protective forces from Sarah Connor so she had to fend for herself.[34] Cameron had also always wanted to make a film about space infantry.[35]

The final script was well received, but Fox executives (including chairman Barry Diller) were concerned about the budget. Fox estimated the cost as close to $35 million, but Hurd said it would be closer to $15.5 million. Diller offered $12 million, prompting Cameron and Hurd to quit. Gordon negotiated with Diller until he relented, and Cameron and Hurd returned.[31] In April 1985, conflict turned to the cast; Fox did not want Weaver to return because they expected her to demand a high salary.[31][38] Cameron and Hurd were insistent Weaver return as the solo star; Fox refused, saying they would damage the studio's negotiating power with Weaver's agent. Cameron and Hurd again left the project, marrying and going on a honeymoon. When they returned, the Aliens project was ready to move forward. Cameron credited Gordon with Aliens' being greenlit.[31]

Casting

[edit]Weaver rejected initial offers to return and despite being interested after reading Cameron's script, she had to be convinced Aliens was not being made exclusively for financial reasons.[30][38][39] Weaver received a $1 million (equivalent to $2.78 million in 2023) salary and a percentage of the box-office profits, the highest salary of her career at the time.[31] Negotiations were so lengthy that Cameron and Hurd told Schwarzenegger's agent they intended to write Ripley out of the movie (knowing Weaver's agent would be told); terms were reached shortly afterward.[30]

Cameron wanted an unknown actor to portray Newt. Agents scouted Henn while she was at school in Lakenheath, England, and though she lacked acting experience, Cameron said she had a "great face and expressive eyes".[43] Stephen Lang auditioned for the role of Hicks, but James Remar secured the role on the recommendation of Hill, his close friend. Remar left shortly into filming, ostensibly due to urgent family matters or creative differences with Cameron, but he later admitted he was fired after being arrested for drug possession.[10][44][45] Hurd hired Michael Biehn the following Friday.[10][45] Paxton credited his casting as Hudson to a chance encounter with Cameron at Los Angeles International Airport, during which he mentioned he would be interested in a role. Fox supported Paxton's casting because of positive feedback for his performance in Weird Science (1985).[46][47] Paxton was worried the character would annoy audiences until he realized he was comic relief for the tense scenes.[46] Henriksen was concerned about portraying Bishop after other recent successful portrayals of android characters, such as Ian Holm in Alien and Rutger Hauer in Blade Runner (1982). He played Bishop as an innocent child who pities the short-lived humans. He suggested wearing distinctive contact lenses to convey when Bishop was alerted to danger, but Cameron believed they would make the character appear more frightening than the aliens.[11] Biehn, Paxton, and Henriksen had worked with Cameron on The Terminator.[11][46]

Aliens was Reiser's first major theatrical role, following small parts in films like Beverly Hills Cop (1984).[10] The Colonial Marines cast features a mix of British and American actors who underwent three weeks of intensive training with the British Special Air Service (SAS).[b] Vietnam War veteran Al Matthews (Apone) helped to train the actors, teaching them how to handle firearms properly because their blanks were still hazardous.[46][48] Before he left, Remar accidentally shot a hole through the set of Frank Oz's Little Shop of Horrors on an adjacent stage.[10][46] The training was intended to help the marine cast develop camaraderie and treat the other actors (Weaver, Reiser, and Hope) as outsiders.[49][50] Biehn's late casting caused him to miss the training, and he said he regretted being unable to customize his armor like the other actors (since he inherited Remar's).[10][45] Cameron created a distinct backstory for each marine and instructed the actors to read Starship Troopers so they would understand the space marine archetype.[51][52][53]

Vasquez was Goldstein's first feature-film role. She credited her physique to spending hours at the gym while unemployed, gaining 10 pounds (4.5 kg) at Cameron's request.[11][54][55] Goldstein wore dark contact lenses and underwent an hour of makeup to cover her freckles and darken her white skin to portray a "Chicano" character; she studied Mexican-American gang interviews to develop her demeanor and accent.[55] Ricco Ross (Frost) was committed to Full Metal Jacket (1987), whose filming schedule overlapped for a week with Aliens'. Although Cameron offered to let Ross join the filming later, Ross was concerned that Stanley Kubrick's projects often overran, and opted for Aliens instead.[11] Rolston misled the filmmakers to get his part; he had finished filming Revolution (1985), and implied he was its most prominent actor after Al Pacino.[14] William Hope (Gorman) was cast as Hudson before Cameron and Hurd decided to take the character in a different direction.[14]

Cynthia Dale Scott (Dietrich) was an aspiring singer when she was cast.[10] Colette Hiller (Ferro) was upset she had to cut her hair short for the role because she was getting married shortly afterward, and made the filmmakers buy her a long, blonde wig.[14] Trevor Steedman (Wierzbowski) was a stuntman rather than an actor,[11] and Aliens was Daniel Kash's (Spunkmeyer) debut film role. He offered Cameron his coat if he got the part and also auditioned for Hudson.[56] The actors stayed at the Holiday Inn in Langley, Berkshire, during filming. Paxton described the actors' time outside work positively: "God, we had the best time ... We all hung very hard together. That's where I first met [Henriksen], who I fell in love with. [Matthews] ... was a really good spirit to have around, with a great voice. And all these hilarious British characters, like [Steedman], the stuntman, who used to grab my bicep and go, 'Blimey, more meat on a cat's cock!'"[46]

Filming

[edit]

Principal photography began in September 1985, on a 75-day schedule, and an $18.5 million budget,[iii] not including film prints and marketing.[31][34][57] Filming took place mainly at Pinewood Studios in Buckinghamshire near London, because of its large sets and the lower cost of filming in England.[c] Filming was difficult as Cameron, a Canadian, had little familiarity with British film-industry traditions such as tea breaks, which interrupted production for up to an hour each weekday, and was frustrated at losing hours of filming every week.[30][38][46] In his book The Making of Aliens, J. W. Rinzler described Cameron as aggressive and certain of what he wanted, which irked the crew. The situation was exacerbated by Cameron's hands-on approach, often modifying setups such as lighting himself to fit his vision without involving the unionized crew.[38]

The crew was dismissive of Cameron for his relative inexperience, thinking he had not done enough to earn such a prominent position, and that Hurd had her job only because she was his partner.[30][57][60] Cinematographer Dick Bush insisted on lighting the alien hive brightly (counter to Cameron's request), and was eventually replaced with Adrian Biddle.[9] First assistant director Derek Cracknell also ignored Cameron's requests.[38][60] Gale described the situation: "[Cameron] would ask him to set up a shot one way and [Cracknell] would say, 'Oh no no no, I know what you want,' ... Then he'd do it wrong and the whole set would have to be broken down."[60] The situation deteriorated until Cameron and Hurd fired Cracknell and the Pinewood crew walked out in the middle of the day.[60]

Cameron called Fox for advice and was determined to move the production out of England until Hurd convinced him otherwise. The situation was tumultuous because the number of films simultaneously in production meant the crew could not be easily replaced. Cameron and Hurd gathered the crew to discuss their grievances; Cameron explained the importance of the production, and that any member of the crew who could not support it should volunteer to be replaced. The crew agreed to support Cameron if he supported their scheduled working hours.[60] The relationship between filmmakers and crew remained cool; when filming concluded at Pinewood, Cameron told the crew: "This has been a long and difficult shoot, fraught by many problems ... but the one thing that kept me going, through it all, was the certain knowledge that one day I would drive out the gate of Pinewood and never come back, and that you sorry bastards would still be here".[60] He described most of the crew as "lazy, insolent, and arrogant".[60] Paxton called the crew's work impeccable, but their attitude more relaxed than the American crews to which he was accustomed.[39]

The power plant and alien nest were filmed in the decommissioned Acton Lane Power Station in London, and the sets were left in place until Tim Burton redressed the sets into interiors for Axis Chemicals during the filming of his 1989 film Batman.[49][61] While filming the dropship descent from the Sulaco, shaking collapsed the set roof onto the cast and crew. Most of the cast were unharmed, but a large piece of debris hit Cameron in the head.[37][62] Because of the tight budget, Hurd made Cameron pay for an early scene of a laser cutting Ripley free from her hypersleep chamber.[37][63] According to Henriksen, Paxton was unaware he would be involved in the knife-trick scene until it was filmed; Henriksen nicked Paxton's finger during the reshoot.[37] Some of the early establishing scenes were filmed near the end of principal photography to capture the bond that had developed between cast and characters.[50]

Some improvisation was encouraged.[64] Weaver discussed tweaks to her character with Cameron on set, believing she understood how Ripley would act.[39] Her line "Get away from her, you bitch!" had to be filmed in one take due to the tight schedule remaining, and the actress thought she had messed it up.[65] Paxton believed he was not good at improvisation and discussed ideas with Cameron before filming. Hudson's signature line "Game over, man; game over!" originated from Paxton developing a backstory for the character, in which he was trained on simulators.[2] Henn found it hard to act afraid of the aliens (since she was fond of the actors in the suits) and imagined a dog was chasing her.[43] Other cast members spent time with Henn between scenes, including Weaver and Paxton (who would color or craft things with her).[43][54] Biehn said he and Paxton spent much of their free time together.[10] Despite the difficulties, Fox was satisfied with the daily footage, and principal photography concluded in January 1986, on time and on budget.[31][66]

Post-production

[edit]Post-production began in late April 1986.[31] Several scenes were removed from Aliens' theatrical release, including Ripley learning about her daughter's death and a cocooned Burke begging her for death.[19] Fox and Hurd suggested removing a long opening scene detailing the lives of the colonists, Newt's family discovering the derelict alien ship, and her father being attacked by a facehugger, because it ruined the pacing and sense of mystery.[37][67] Two scenes with James Remar as Hicks (shown from the back) were used in the film.[10]

Ray Lovejoy was responsible for editing the final two hours, 17 minutes cut of Aliens.[68] Fox wanted the film to be under two hours so it could be shown more times per day in theaters, increasing its revenue potential. Fox production president Scott Rudin flew to England to ask Cameron and Hurd if they could cut another 12 minutes, but Cameron was concerned further cuts would make it nonsensical, and Rudin relented.[31][68]

Music

[edit]James Horner met Cameron early in their careers, when they worked for director Roger Corman. Aliens was Horner and Cameron's first collaboration; Horner called it a "nightmare".[71][72] He arrived in London to compose, expecting a six-week schedule. There was nothing for him to score, as Cameron was still filming and editing, and Horner had only three weeks to compose.[30][72][70] The producers were unwilling to give him any more time, and he was booked to begin scoring The Name of the Rose (1986) shortly afterwards.[70]

Horner recorded the score at Abbey Road Studios with the London Symphony Orchestra.[72][73] His schedule was so tight that the music for the climactic battle between Ripley and the queen was written overnight. Cameron first heard the score while it was being recorded by the orchestra and did not like it, but it was too late to make changes. Brad Fiedel's synth-inspired tracks for The Terminator had allowed changes to be made quickly based on feedback, but Cameron had no experience managing orchestral music.[70] Cameron cut the score up, using pieces where he believed they fit best, and inserted pieces of Jerry Goldsmith's Alien score and hired unknown composers to fill gaps.[70][73] The director said in a later interview he thought the music was good, but did not fit the scenes he had filmed.[70] Horner's "alien sting" sound was initially used only once, during the scene with the cocooned woman, as Cameron disliked it, but he eventually used it throughout the film.[37] Unused portions of Horner's Aliens score were repurposed for Die Hard (1988).[74][75]

Special effects and design

[edit]Development of the special effects for Aliens began in May 1985, with John Richardson supervising a 40-person team at Stan Winston Studio.[39][76][77] L.A. Effects Group created miniatures and optical effects. Cameron lacked contacts at the more established special effects studios and avoided using them because he believed his hands-on approach would not be welcomed.[78] He also did not rehire many Alien crew members because he did not want to be restricted by their loyalties to the first film. Those who returned were often given a higher status (such as Crispian Sallis, Alien focus puller and Aliens set decorator).[58][79] Cameron had enjoyed returning artist Ron Cobb's work on Alien,[80] and conceptual artist Syd Mead was recruited because Cameron was a fan of his work on films such as 2010: The Year We Make Contact (1984).[59]

Sets and technology

[edit]Mead designed the Sulaco, the marines' spaceship. He conceived it as a large sphere with antennae, but Cameron wanted it to be flatter; the full craft had to pass the camera, and a sphere would not work with the aspect ratio.[39] Mead designed the craft as a commercial freighter carrying a military unit. Its exterior was designed with a row of loading doors, a crane, and large gun fixtures to defend against threats.[81] Mirrors were used as a cost-cutting measure to increase the number of sleeping pods and add a power loader.[56] Cobb designed the dropship, the armored personnel carrier (APC), and exteriors of the colony and its vehicles.[82][83][84] The Sulaco's dropship was designed to be life-size, for use on the Sulaco set,[59] but a smaller replica was used for some shots.[81] The APC was a disguised pushback tug for a Boeing 747.[81] The derelict alien spacecraft used in Aliens had been in historian Bob Burns III's driveway since its appearance in Alien.[37]

Most of the colony, apart from the main entrance used by the marines, was constructed in scale miniature form. The set was about 80-foot (24 m) long to accommodate the sixth-scale APC replica. The set was so large it had to be laid out diagonally across the stage, and forced perspective was used to add in buildings that would otherwise not fit.[85] Cobb used a stylized design for the colony, resembling a western frontier town. It featured a makeshift construction from cargo containers, broken filming equipment, and beer crates.[86] The alien nest scene was one of the earliest filmed; Weaver's participation was delayed by three weeks because of production issues on her previous film Half Moon Street (1986), and the scene was one of the few not involving her. The Acton Power Station location was filled with decaying asbestos and three weeks were spent having it professionally cleaned, during which time the alien hive was fabricated in clay spawning hundreds of fiberglass and vacuum-formed castings that were installed at the station over a further three weeks.[87] Cameron wanted to vertically pan as the marines entered the hive, but disguising the area above the marines would be time-intensive. A hanging miniature, about 12-foot (3.7 m) square, was made from plywood and styrofoam, hung just above the actors' heads, and carefully blended into the larger set. After Remar was replaced, Cameron wanted to reshoot the scene, but the miniature had been destroyed; he was able to edit the scene to conceal Remar.[88]

The marines' smart guns weighed 65 to 70 pounds (29 to 32 kg), and were constructed from German MG 42 machine guns attached to a steadicam and augmented with motorcycle parts.[89][90] Since getting in and out of the smart-gun rig was difficult, the actors kept them on when not filming.[11] The pulse rifle was made from a Thompson submachine gun and a Franchi SPAS-12 pump-action shotgun in a futuristic shell.[91] Weaver was opposed to weapons in general, but Cameron explained weapons were secondary to the core narrative of Ripley bonding with and protecting Newt.[38][39][91] Weaver found using the weapons strange and difficult, due to their weight and her concern about pulling the wrong trigger.[39][91] Automated sentry guns were also constructed for Aliens, although they do not appear in the theatrical cut. Real machine guns were positioned atop remote-controlled hydraulic tripods that allowed them to pivot horizontally or vertically. The guns were capable of firing up to 600 wooden-blank rounds per minute that were shattered into small splinters by baffles in the muzzle and incinerated by the heat generated in the barrel.[92]

A cast was made of Henn's upper body and her stunt double's legs to construct a lightweight dummy for Weaver to hold when carrying a gun; Henn's weight plus a gun would have been too heavy.[39] Goldstein had never handled a gun, and held her weapon incorrectly in closeups, so Hurd stood in for her.[37] The flamethrowers were functional. The art department had covered the sets in an unspecified substance to artificially age them; the flamethrowers vaporized it, causing fire and heavy smoke. Goldstein struggled to breathe and, since improvisation was encouraged, Paxton thought she was acting until he also became breathless.[37][64]

The nuclear explosion of the colony in the finale was created by shining a light bulb through cotton.[37] Reebok designer Taun Le was commissioned to design custom sneakers for Weaver to wear in the film. The only mandate was that they be laceless so one could easily slide off of Weaver's foot during the finale.[46][93]

Creature effects

[edit]H. R. Giger, who designed the alien creature, was reportedly disappointed that he could not be involved in Aliens.[94] According to Hurd, Giger was contractually obligated to Poltergeist II: The Other Side (1986) and Fox was not allowed to negotiate with him.[95] Giger was replaced by special-effects creator Stan Winston. Cameron also contributed to designs but was not as concerned with the warrior aliens because they were on screen only briefly.[94] In redesigning the alien warriors, Cameron remained faithful to Giger's work while building on it. Conscious that the creatures would be seen by audiences as people in costumes, he enhanced the designs by extending their arms and often filmed them hung from wires or from atypical positions to make them appear more inhuman.[58] The aliens were played by dancers and stuntmen in lightweight costumes that allowed them to move quickly. Several 8-foot (2.4 m) mannequins were used for aliens that were contorted into inhuman poses.[39] Although hordes of alien creatures appear to be in the film, there were only 12 alien suits: simple black leotards covered in molded foam were used for faster-moving shots, and detailed models with articulated upper bodies and mouths for closeups.[96] When the aliens were shot and destroyed, puppets were hung up and detonated. The aliens' acidic blood was a combination of titanium tetrachloride, cyclohexylamine, acetic acid and yellow dye.[39]

The facehugger design remained faithful to the original Alien design, but the overall appearance was made to appear more organic, and its eight legs were made more finger-like, enhancing the detail on the knuckles and adding fingernails.[97] Unlike in Alien, which only involved one substantial jumping scene, the facehugger models used in Aliens featured full articulation for their tongue, legs, and tail, allowing for more action set pieces. The tail was also lengthened about 6 in (15 cm) to give it more functions such as a whip-like action.[97] Nine operators were required for the fully articulated facehugger; other less-detailed variants were used for simple actions such as scurrying across the floor. The design team struggled with making it scuttle believably while moving the appendages; they eventually developing a control wire along the floor that activated a gear inside it, causing the appendages to move as it was pulled along. Several rubber facehuggers were made to be thrown or blown up.[98] Manipulating the facehugger inside a water tank was also difficult as the tank had to be watertight, limiting the use of control cables. A method was developed that required fewer cables to move the facehugger around the tank; the tail was fitted with a spring that caused it to snap back and forth.[97] Winston added arms to the chestburster alien form (since the adult form had arms), explaining how it could drag itself out of a host's chest. Two chestburster puppets were used: a reinforced one, and an articulated one for movement. A puppeteer punched the former through a fabricated latex-foam chest; the scene took several takes to film because it could not pierce the clothing.[17][99]

A deleted scene in Alien established a life cycle for the alien creatures in which a lifeform would be cocooned and transformed into an egg that birthed a facehugger.[58][100] Inspired by a beehive-like hierarchy, Cameron believed the vast field of eggs on the derelict alien craft would come from a much larger creature, the queen, with the other alien creatures serving as her drones.[58] Winston described Cameron's initial queen design as a combination of a praying mantis and Tyrannosaurus rex influenced by the alien warrior design.[94][101] Cameron said dinosaur influences were unintentional as he considered them "boring"; his goal was to extrapolate on Giger's warrior designs to create a large and powerful creature that was also swift and overtly female, describing it as "hideous and beautiful at the same time, like a black widow spider". The queen has elongated, large forelimbs, with smaller secondary ones underneath, but Winston redesigned the legs by adding a double joint to make it more inhuman.[101] Cameron and Winston worked on several concepts to vivify the queen, including large puppets, miniatures, and costumes with several people inside. A frame was built large enough to hold two people, covered in black polythene bags, and hung on a crane. The prototype was a success, and Cameron wrote the alien-queen scene.[37][102] The final alien queen was a 14-foot (4.3 m) puppet made of lightweight polyurethane foam.[90] Two people sat inside to control the arms; the legs were controlled by rods connected at the ankles, and a separate person whipped the tail around with fishing line. The head was manipulated with a combination of servomotors and hydraulics controlled by up to four people. The effect was hidden by lighting, steam, slime, and smoke.[37][102] The Stan Winston Studio had not used hydraulics and considered them a learning experience. They were essential for moving larger parts of the queen puppet, including the head, and a foot pedal in the body could hydraulically move the tail up and down.[76] Shane Mahan took several weeks to sculpt the head by sight, based on a maquette; computer technology to scale up the model's design did not yet exist.[103] Two heads were built: a lightweight, fragile one; and another that could survive some damage. Each was articulated with hydraulics and cables to control the queen's mouth and lips.[76]

To create the effect of the queen piercing Bishop's chest with her tail, Tom Woodruff Jr. and Alec Gillis constructed a chestplate for Henriksen with a rubber segment of the queen's tail flattened against it. The tail was pulled forward by wire, apparently exploding through Bishop's torso. A rigid piece of tail, attached to a body harness, was used to show more of the tail moving through Bishop, and Henriksen was levered upward as if he was being lifted by the tail. To complete the effect, a dummy of Bishop was constructed with a spring-loaded mechanism that forcibly separated his upper and lower body, as if the queen had ripped him in half. Once separated, Henriksen's upper body was below the set and a fake torso attached up to his shoulders. The android blood was milk, and after several days of filming, it was sour and foul-smelling.[104]

John Richardson designed the mechanical power loader exosuit, with input from Mead. As with the queen, a prototype was built out of wood and polythene bags stuffed with newspaper to see how the movement would work.[39][59][102] The finished design was so cumbersome that stuntman John Lees, in a black skinsuit, operated it from behind.[39][102] The battle between the queen and power loader was extensively choreographed, as Weaver risked serious injury battling a large, unwieldy animatronic.[102] The camera was sometimes moved to simulate subjects moving faster. The scene of the queen running at Ripley was one of the more difficult shots; the wires and rods had to be concealed, since they could not be removed in post-production.[102] Miniatures were used for parts of the scene with go motion, a version of stop motion with motion blur added.[102]

Release

[edit]Context

[edit]

The 1986 summer film season began in mid-May. The season had been starting earlier each year as studios attempted to beat each other with their biggest films. Fifty-five films were scheduled for release between May and September, including the action drama Top Gun and the comedic Sweet Liberty, but the season was not expected to break financial records due to fewer sequels, anticipated blockbusters, and films by Steven Spielberg or starring popular comedians that had dominated the earlier half of the decade. Some industry experts also blamed the burgeoning home-video market, which had grown from 7 million rentals in 1983 to 58 million by 1985.[105][106] Films expected to do well were aimed at younger audiences and featured comedy or horror, such as Back to School, Ferris Bueller's Day Off, and SpaceCamp.[106] Some films targeted at adults were also seen as potential successes, including Legal Eagles, Ruthless People, and Cobra.[106]

Aliens was seen by industry professionals as a potential sleeper hit based on positive industry word-of-mouth during filming, enthusiastic industry screenings, and favorable pre-release reviews.[31][35][91] The film's success was considered dependent on its ability to attract audiences outside the young males and blue-collar workers typical for the genre.[107] The tagline was, "This time, it's war".[90]

Box office

[edit]Aliens began a wide release in the United States (U.S.) and Canada on July 18, 1986.[9] During its opening weekend, the film earned $10.1 million from 1,437 theaters—an average of $6,995 per theater. It was the weekend's number-one film, ahead of the martial-arts drama The Karate Kid Part II ($5.6 million in its fifth weekend) and the black comedy Ruthless People ($4.5 million in its fourth weekend).[108] Based on its opening-five-day total ($13.4 million), Aliens exceeded Fox's expectations and was anticipated to become the summer's top film, surpassing The Karate Kid Part II, Back to School, and Top Gun.[31][107] The Los Angeles Times reported long lines to see Aliens, even on weekday afternoons.[31]

The film retained the number-one position in its second weekend with an additional gross of $8.6 million, ahead of the debuting comedy-drama Heartburn ($5.8 million) and The Karate Kid Part II ($5 million).[109] Aliens remained the number-one film of its third weekend with a gross of $7.1 million, ahead of the debuts of Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives ($6.8 million) and the comedy Howard the Duck ($5.1 million).[110][111] The film fell to third place in its fifth weekend with a gross of $4.30 million, behind the debuts of the science-fiction horror film The Fly ($7 million) and the comedy Armed and Dangerous ($4.33 million).[112] Aliens was one of the top ten highest-grossing films for 11 weeks.[113]

By the end of its theatrical run, Aliens had grossed about $85.1 million.[113][114][iv] This figure made it the year's seventh highest-grossing film, behind Back to School ($91.3 million), science-fiction film Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home ($109.6 million), The Karate Kid Part II ($115.1 million), war film Platoon (138.5 million), action comedy Crocodile Dundee ($174.8 million) and Top Gun ($176.8 million).[115][116] Aliens' box-office returns to the studio, minus the theaters' share, was $42.5 million.[117]

Box office figures outside the U.S. and Canada are inconsistent and not available for all 1986 films. According to the box-office tracking websites Box Office Mojo and the Numbers, Aliens earned from $45.9 million to $98.1 million.[v] This gives Aliens a worldwide gross of $131.1 million to $183.3 million, making it the year's fourth-highest-grossing film, behind Platoon ($138 million), Crocodile Dundee ($328.2 million), and Top Gun ($356.8 million), or the third-highest-grossing film behind Crocodile Dundee and Top Gun.[118][119] According to Fox's 1992 estimate, Aliens had earned $157 million worldwide.[120][vi] The New York Times described the film as "extremely successful."[117]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]

Aliens opened to generally positive reviews.[107] It appeared on the cover of the July 28, 1986, edition of Time magazine, which called it "The Summer's Scariest Movie".[121] Audience polls by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[122]

Most reviewers agreed Aliens was a worthy successor to Alien.[123][124] Variety and Walter Goodman said it could not replicate the novelty of the first film, but Aliens compensated with special effects, technique, and a constant stream of set-piece thrills and scary scenes.[9][123] Variety added Aliens was made by an expert craftsman, suggesting its predecessor was a more artistic endeavor.[123] Sheila Benson said Aliens was clever and ironically funny, but lacked Alien's pure horror. Benson attributed this to an overabundance of creature effects in the intervening years, particularly the 1982 science-fiction horror film The Thing (which, Benson said, took alien monstrosities to an extreme).[125]

According to Rick Kogan, Aliens demonstrated that science-fiction horror could still be entertaining after many poorly received Alien-derived films.[126] Dave Kehr and Richard Schickel called it a rare sequel which surpassed the original, and Kehr appreciated the action used to develop the characters. Schickel wrote that the film had evolved from Alien, giving Weaver new emotional depths.[124][127] Jay Scott said Cameron had redefined the war film, combining Rambo with Star Wars.[128] Kogan agreed Cameron possessed a knack for action pacing and excitement, but Kehr believed Cameron pushed some elements beyond believability.[126][127]

Roger Ebert called the last hour "painfully, unremittingly intense" in horror and action, leaving him emotionally drained and unhappy. Ebert believed it could not be defined as entertainment, despite his admiration of the filmmaking craft on display.[129] Dennis Fischer wrote for The Hollywood Reporter that the unrelenting scenes of action and suspense worked for Aliens as they had in The Terminator; tension was created by placing the characters in successive, increasingly difficult situations.[130] Gene Siskel described the film as "one extremely violent, protracted attack on the senses".[131] In the Orlando Sentinel, Jay Boyar called it the Jaws of the 1980s: the most "intensely shocking" film in years.[132]

Reviewers consistently praised Weaver's performance.[123][129] Benson called her the "white-hot core" around whose "defiant intelligence" and "sensual athleticism" Aliens was built, and Ripley returned not for vengeance but out of compassion.[125] Ebert credited Weaver's sympathetic performance with holding Aliens together.[129] Kogan compared her to a more attractive John Rambo (Sylvester Stallone's action character).[126] Scott agreed, saying Weaver made action stars like Stallone and Schwarzenegger look like male pin-up models. He described her as the ultimate adventure heroine, balancing action with femininity and maternal instincts.[128] Pauline Kael was critical of the film overall as too "mechanical", but praised Weaver's physical presence and performance, writing that, without her, Aliens was a subpar B picture.[133]

Most of the cast was also praised, particularly Biehn, Goldstein, Henriksen, Henn and Reiser[123][125][129] but Benson noted that less time was spent exploring the new characters than in Alien.[125] Schickel said Henn played her character as endearingly brave and clever, without self-pity.[134] Benson praised Horner's "ruminative, intelligent" music,[125] but Fischer criticized it for borrowing too much from Goldsmith's score and Horner's work on Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1984).[130]

Accolades

[edit]

Aliens received two awards at the 1987 Academy Awards: Best Sound Effects Editing (Don Sharpe) and Best Visual Effects (Robert Skotak, Stan Winston, John Richardson, Suzanne Benson). Weaver was nominated for Best Actress, losing to Marlee Matlin for the romantic drama Children of a Lesser God.[135] Weaver's was the first Best Actress nomination given for a science-fiction film, at a time when the genre was given little respect, and it remained a rarity for the action or science-fiction genres.[136][137][138] The film garnered four other nominations: Best Original Score for Horner; Best Art Director for Peter Lamont and Crispian Sallis; Best Editing for Ray Lovejoy, and Best Sound for Graham V. Hartstone, Nicolas Le Messurier, Michael A. Carter, and Roy Charman.[135] At the 44th Golden Globe Awards, Weaver was nominated for Best Actress in a Drama.[139]

At the 40th British Academy Film Awards, Aliens won the award for Best Special Visual Effects and three other nominations: Best Production Design, Best Makeup and Hair for Peter Robb King, and Best Sound.[140] At the 14th Saturn Awards, Aliens received eight awards: Best Science Fiction Film, Best Actress (Weaver), Best Performance by a Young Actor (Henn), Best Supporting Actress (Goldstein), Best Supporting Actor (Paxton), Best Special Effects (Winston and the L.A. Effects Group) and Best Director and Best Writing (both for Cameron).[141] It received a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation.[142]

Post-release

[edit]Home media

[edit]Aliens was released on VHS in February 1987.[143][144] A modified cut, including scenes deleted from the theatrical release, was broadcast on CBS in 1989, and a further extended edition with more deleted scenes, including the opening scene of Newt's family investigating the derelict spacecraft, was released on LaserDisc in 1991. The extended cut is 157 minutes long, 20 minutes longer than the theatrical cut, and Cameron has stated it is his preferred version.[25][145][146]

The extended edition was released on VHS and DVD in 1999 as part of the Alien Legacy box set with the other three available Alien films: Alien, Alien 3 (1992) and Alien Resurrection (1997).[145] The DVD version was also sold separately, and both versions included additional behind-the-scenes footage.[147] The 2003 Alien Quadrilogy nine-DVD box set included all four films and an additional disc for each film with behind-the-scenes footage and featurettes (including a three-hour documentary, Superior Firepower: The Making of Aliens), and theatrical and extended cuts of each film. The Aliens disc included commentary by cast and crew members, including Cameron; Weaver did not participate. Each film was sold separately (including its bonus disc) in 2004.[25][148]

Aliens was released on Blu-ray in 2010 as part of the Alien Anthology box set with remastered footage, theatrical and extended versions, and featurettes found in earlier releases. The film was released separately on Blu-ray in 2011.[149][150] For its 30th anniversary in 2016, Aliens was released on Blu-ray and digital download, featuring a new interview with Cameron about his inspirations for the film. In addition to the theatrical and extended versions, the release contained a limited-edition lithograph of Ripley in battle with the alien queen, an art book focused on the Aliens comic books by Dark Horse Comics, and collectible cards with concept art by Cameron.[151] A limited-edition, 75-copy vinyl soundtrack was also released that year.[152] A 4K Ultra HD remastered Collector's Edition of Aliens was made available for digital release in December 2023, followed by a 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray release in March 2024.[153] This release received some criticism for the use of artificial intelligence to improve the image quality, which resulted in some overly smooth and uncanny results.[154][155]

Other media

[edit]Toy company Kenner Products attempted to release figures based on Alien in 1979, but only an alien action figure was released, which was quickly withdrawn when it was deemed too frightening for children. Aliens was considered a different prospect (despite its adult-oriented content), since it focused on action and featured marines (instead of ordinary workers) fighting a large number of aliens. The toys were intended to tie into Operation Aliens (a children's cartoon scheduled for release in 1992, alongside Alien 3) and a series of mini-comics by Dark Horse Comics.[156][157] Since its release, Aliens has appeared across a variety of merchandise, including action figures,[157] punching bags,[152] clothing,[152] and board games.[158] McFarlane Toys released figures for Hicks, the alien, and the alien queen in the early 2000s.[159][160][161] In the late 2010s, National Entertainment Collectibles Association (NECA) released figures based on the film, including Newt,[23] Burke, and Cameron dressed as a Colonial Marine.[162][163] NECA also revived the original Kenner designs in 2019, releasing better-quality models.[164][165]

Aliens has had several video-game adaptations, beginning with Aliens: The Computer Game (1986), which was followed by a separate game, also called Aliens: The Computer Game, in 1987. A side-scroller, Aliens (1987), was released in Japan for the MSX,[166] and a 1990 arcade game, Aliens, allowed players to play as Ripley or Hicks against alien variants; some levels required the player to control Newt.[166][167] Aliens: A Comic Book Adventure, an adventure game focusing on puzzles, was released in 1995.[166][168] A first-person shooter, Alien Trilogy (1996), is based on Alien, Aliens, and Alien 3.[166][169] Aliens Online (1998) was an online game which allowed players to play as Colonial Marines or aliens.[166] Aliens: Colonial Marines (2013) is a first-person shooter and a canonical sequel of Aliens, focusing on the marines sent to search for Ripley's expedition.[166][168] Several other games have the Aliens brand or are side stories or sequels to the film's events, and the Aliens vs. Predator game series.[d]

A novelization by Alan Dean Foster was released alongside the film.[171][172] Comic books based on (and continuing) the story of Aliens have been published (primarily by Dark Horse Comics) since 1988, including crossovers of the titular aliens with popular franchises, such as Predator (creating a derivative Alien vs. Predator franchise), Terminator, and Superman.[e] Reebok's boots designed for Ripley became available to the public in 2016; other versions included boots based on the power loader, Bishop, the Colonial Marines and the alien queen.[93][152] Rinzler published The Making of Aliens, a 300-page behind-the-scenes book with cast and crew interviews and previously unseen photographs, in 2020.[94] Operation Aliens, a board game, was released in 1992. Players are cast as a Colonial Marine or Ripley and tasked with finding a self-destruct code to destroy an infested spaceship.[158][182]

Themes

[edit]Motherhood

[edit]A central theme of Aliens is motherhood.[38][183] Alien can be seen as a metaphor for childbirth, but Aliens focuses on Ripley's maternal feelings for Newt. A scene cut from the theatrical release depicts Ripley learning her child died while she was in stasis, helping explain Ripley's motherly attention for Newt. Newt has also lost everything of value, and they form a new family from the remnants of their old ones.[134][183] This relationship is mirrored by the alien queen, mother of the alien creatures.[183][184] There are no paternal figures; both are single mothers, defending their young. The alien queen seeks revenge against Ripley, who destroyed her brood and her means of reproduction.[124][183] According to Richard Schickel, Alien is about survival; Aliens is about fighting to ensure someone else's survival.[134]

Authors Tammy Ostrander and Susan Yunis believed Newt's capture by the aliens forces Ripley to realize she is willing to die to save her, demonstrating a selfless motherhood, unlike the queen's selfish motherhood.[185] Writing for the Los Angeles Times, Nancy Weber wrote that as a mother, she saw in Aliens the constant vigilance required to protect her child from predators, sexism, and threats to childhood innocence.[186] Leilani Nishime believed despite the focus on motherhood, the nuclear family is represented in Aliens with a mother (Ripley), father (Hicks), daughter (Newt), and a loyal, self-sacrificing dog (Bishop).[187]

According to Charles Berg, the depictions of aliens in science fiction that became more popular during the 1980s represented American fears of immigrants (the "other"). In Aliens, this can be seen in the white-skinned single mother (Ripley) confronting the dark-skinned alien queen with an endless brood.[188] Ostrander and Yunis also identified fears of overcrowding, dwindling resources, and pollution, suggesting the alien queen demonizes motherhood and makes it less attractive. She represents mindless, unchecked maternal instinct spawning armies of children, regardless of the lives which must be sacrificed to ensure their survival. Despite imminent destruction by the colony exploding, the queen continues to reproduce.[189] The aliens' life cycle taints the reproductive cycle. Creation involves rape, and birth involves a violent death.[190] In destroying the aliens and their queen, Ripley rejects the unchecked proliferation of their species and sets an example for her own.[191]

Masculinity and femininity

[edit]

Ripley has been compared to John Rambo and dubbed Ramboette, Rambette, Fembo, Ramboline; Weaver called herself Rambolina.[39][192][193] Mary Lee Settle said females in television and film had evolved from escapist fantasy to more accurately reflect their audiences. A gun, which can be seen as a phallic symbol, has a different meaning when wielded by Weaver.[192] Schickel described Ripley as transcending the customary boundaries imposed on her gender, where females serve the male hero. In Aliens, the male characters are neutralized by the climax and Ripley faces the queen alone.[32] Cameron said he does not like cowardly female characters and removes their expected protectors to force them to fend for themselves. He called the overuse of male heroes "commercially shortsighted" in an industry whose audience is 50-percent female, and where "80 percent of the time, it's women who decide which film to see".[32][34]

The growth of female-led action films after the success of Aliens reflects the change in women's roles and the divide between professional critics (who perceive a masculinization of the heroine) and audiences that—regardless of gender—embrace, emulate, and quote Ripley.[194] The hyper-masculine heroes played by Schwarzenegger, Stallone, and Jean-Claude Van Damme were replaced by independent women capable of defending themselves and defeating villains in films such as The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and Cameron's Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991).[195] These female characters often perform stereotypical male actions, and have muscular physiques rather than feminine "soft" bodies.[196] When Ripley has seized command of the marines and is no longer a passive outsider in Aliens, the traditional male hero (Hicks) instructs her in the use of their weapons.[197] The comparison of Ripley to Rambo conflates her with the male, musclebound, gun-wielding action hero.[198] To balance her masculine traits, Cameron gives Ripley maternal instincts; this counters homophobic audiences, who might see a masculinized female as lesbian or butch.[199] These traits are further offset by the more openly masculine Vasquez, a minor character. Vasquez (who has short hair and bigger muscles) is introduced to the audience by working out, and is asked if she has ever been mistaken for a man.[200] Weber appreciated the change in female characters between the films, contrasting Alien's hysterical Lambert with the tough Vasquez (who sacrifices herself for her team, not only for the protagonist).[186]

War and trauma

[edit]Aliens has been described as an allegory for the Vietnam War; the marines (like the United States) have superior weaponry and technology that proves largely ineffective against an unseen, local enemy.[34][90] Like some Vietnam veterans, Ripley developed post-traumatic stress disorder after the events of Alien.[201] Writer Joe Abbott contrasted the depiction of the military in Aliens to the 1954 science-fiction film Them! In both films, humans are beset by a monstrous invasion; in Them!, the military is the hero despite its responsibility for the infestation. Abbott said its post-World War II American setting depicts a competent military and a state authority that demands (and receives) the compliance of its citizens. The image of the post-Vietnam military is tarnished and scrutinized; in Aliens, it is ill-equipped, bumbling, and incapable of combating the threat posed by the alien creatures. Citizen cooperation can no longer be demanded or expected, and it is Ripley, an independent contractor from outside the state and military infrastructures, who saves the day.[202] Unlike Them!, the military is not at fault for creating the problem in Aliens; it is the Weyland-Yutani corporation ("the company"). The power of the state has been superseded by the corporation, which also demands conformity for rewards and advancement and reflects a growing mistrust of corporatism; the company is represented by Burke, a self-interested opportunist.[203] Ripley is elevated throughout Aliens as she prioritizes the survival and safety of all humans while Burke is often willing to callously sacrifice human life in pursuit of the interests of the company.[204]

According to Weaver, Aliens is about confronting trauma to obtain closure.[205] This may be seen as a reflection of Ronald Reagan's United States presidency and a conservatism that believed the hero must return to confront their fears with ethics and morality on their side.[206][207] Comparing Alien with Aliens, Roger Luckhurst said: "Even if Alien was a piece of leftist science fiction, the core of [its] myth could be inflected the other way. [Cameron's] Aliens would be a defiantly Reaganite version of the story—pumped, militarized, libertarian driven by a staunch defense of the nuclear family."[208] Abbott said Aliens adheres to a radical ideology and condemns centrism; similar films were popular because they represented audience dissatisfaction with the social status quo.[202] The film places power in the individual (Ripley), instead of institutions like the military, corporations, or the government.[209] The Bishop character also allows Ripley to confront her distrust of androids that resulted from the deception of Ash (portrayed by Ian Holm) in Alien. Unlike Ash, Bishop is openly an android and conveys both a similarly unassuming personality and a fascination with the alien creatures. Aliens imbues Bishop with a degree of humanity as he volunteers for a potentially suicidal mission. Although the other characters assume he is artificial and thus unafraid, Bishop affirms, "Believe me, I'd prefer not to, I may be synthetic, but I'm not stupid."[210]

Legacy

[edit]Cultural influence

[edit]

A cinematic touchstone, Aliens has had an enduring influence on filmmaking.[f] Elements such as a team of soldiers being dismantled by a villain have been repeated to the point of cliché.[90] The same is true of Horner's oft-imitated score,[69][90] which regularly appeared in action-film trailers for the following decade.[71][70] The film's influence can also be seen in video games' (particularly science-fiction games') ships, armor, and weapons,[214][215] as well as the 1989 Italian film Shocking Dark, a remake of Aliens that relocates much of the plot and scenes to a Venetian setting and incorporates elements of The Terminator; outside Italy, it was released as Terminator II.[216] In Avengers: Infinity War (2018), Spider Man discusses the film with Iron Man, and the two use the xenomorph queen's defeat as inspiration for how to kill Ebony Maw and free Doctor Strange.[217]

Although The Terminator was a success for Cameron, the critical and commercial success of Aliens made him a blockbuster director. It also expanded the Alien series into a franchise, spanning video games, comic books, and toys; although Ripley and the alien creature originated in Alien, Cameron elaborated on the creature's life cycle, added new characters and factions (such as the Colonial Marines), and extended the films' universe.[90] Ripley became a post-feminist icon, a proactive hero who retained feminine traits.[90] Aliens features popular quotes, including Paxton's "Game over, man; game over",[213][218] and Weaver's "Get away from her, you bitch," which is considered one of Aliens's most memorable lines and has often been repeated in other media.[90][219] Aliens was named by director Roland Emmerich as one of his top ten science-fiction films, alongside Alien.[220]

Many cast and crew members reunited at the 2016 San Diego Comic-Con to celebrate the film's 30th anniversary, including Weaver, Biehn, Paxton, Henriksen, Reiser, Henn, Cameron and Hurd. Cameron said he normally would not participate (and did not do so for The Terminator's anniversary) but he considered Aliens special because of its impact on his career.[151][213] Asked why he thought Aliens' popularity had endured, Cameron said:

I have to take my filmmaker hat off and look at it as a fan and think, "Well, I really like those characters ..." There's certain lines, moments, you remember moments. It's satisfying, it ends in a satisfying way ... But I actually think it's those characters. We can all relate to Hudson running around "What the hell are we gonna do now man? What the fuck we gonna do?" We all know that guy.

Hurd believed that it was the experience itself:

It's a great midnight screening movie because you can talk back to the screen and you can have this group experience. It not only makes you feel something, it makes you cheer, it makes you jump. When you think of all the things that something can do, which is projected on a screen, it ticks all those boxes and it makes you laugh.[221]

The ensemble cast's popularity led to many members appearing together in later films, including Henriksen, Goldstein, and Paxton in Near Dark (1987) as well as Goldstein and Rolston in Lethal Weapon 2 (1989).[50] Biehn lost a role in Cameron's Avatar (2009) because Weaver had been cast, and the director did not want to create an obvious association with Aliens.[10] Paxton is also remembered as one of only two actors, along with Lance Henriksen, to play characters killed by an alien, a Terminator (in The Terminator), and a Predator (in 1990's Predator 2).[54] Despite her sudden fame, Henn decided not to pursue acting, so that she could remain close to her family. She said some people resented her fame and was uncertain whether people liked her for being in Aliens or for herself. Henn became a teacher; she maintains a relationship with Weaver and kept a framed picture of her and Weaver that the actress had given her after filming was complete.[43]

Critical reassessment

[edit]Aliens is considered one of the greatest science-fiction films ever made,[g] as well as being among the best films of the 1980s,[h] and one of the greatest action films of all time.[i] The British Film Institute called Aliens one of the 10 greatest action films, saying: "A matriarchal masterpiece of God-bothering structural engineering, there's really little that Aliens doesn't get right; from its slow-burn exemplification of character and world-building through to its jab-jab-hook-pause-uppercut series of sustained climaxes, Cameron delivers a masterclass in action direction."[3]

The film is also considered one of the best sequels of all time, and equal to (or better than) Alien.[j] According to Slant Magazine, it exceeded Alien in every way.[4] In 2009, Den of Geek called it the best blockbuster sequel ever made, and remarkable even as a standalone film.[5] In 2017, the website ranked it the second-best film in the series (behind Alien).[247] In 2011, Empire called it the greatest movie sequel ever.[248] Empire also listed Aliens as the 30th-best film ever made on the magazine's "500 Greatest Movies Of All Time" list; its readers ranked it the 17th-best.[249][250] The film is listed in the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die.[251] Aliens has a 94% approval rating on the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes from 140 reviews, with an average rating of 8.9/10. Its critical consensus reads, "While Alien was a marvel of slow-building, atmospheric tension, Aliens packs a much more visceral punch, and features a typically strong performance from Sigourney Weaver."[252] The film has a score of 84 out of 100 on Metacritic based on 22 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[253]

The Ellen Ripley character has also been recognized; the American Film Institute ranked her the eighth-most-heroic character on its 2003 100 Years ... 100 Heroes and Villains list,[254] and she was ninth on Empire's 2006 "100 Greatest Movie Characters" list.[255] Despite her character's popularity, the casting of Jenette Goldstein (a Jewish actress of Russian, Moroccan, and Brazilian descent) as the Hispanic Vasquez has been considered odd. Goldstein has said she considers herself unrecognizable as Vasquez on film, but a muscular actress was required, and the filmmakers could not find anyone else with her physique.[256]

Franchise

[edit]Aliens' success resulted in immediate discussion of a sequel.[31] Alien 3 was released in 1992, after a tumultuous development involving several writers and directors; Cameron did not return.[257][258][259] The film was financially successful, but "generally panned" by critics, and its director, David Fincher, disowned it after the release, citing studio interference.[257] The film was also derided by fans because it killed the Hicks and Newt characters off-screen. Biehn called it one of his greatest disappointments and refused permission for the use of his likeness in Alien 3.[10][260] Regarding the treatment of his characters, Cameron said:

I thought [the decision to eliminate Newt, Hicks, and Bishop] was dumb ... I thought it was a huge slap in the face to the fans ... I think it was a big mistake. Certainly, had we been involved we would not have done that, because we felt we earned something with the audience for those characters.[37][261]

An early script for Alien 3, by William Gibson, was adapted as a 2019 audio drama, focusing on Hicks as the protagonist, with Biehn and Henriksen voicing their respective roles.[259][262] A five-hour 2017 audio drama, River of Pain, takes place between Alien and Aliens and covers the early days of the LV-426 colony and its downfall to the aliens. Actors returning to voice their characters included William Hope, Mac MacDonald, Stuart Milligan, and Alibe Parsons.[27] A third sequel, Alien Resurrection, was released in 1997.[263] Instead of a fourth sequel, Fox began development of a prequel crossover film, Alien vs. Predator (2004), pitting the series' aliens against the titular alien race of its science-fiction property, Predator;[264][265] the film was poorly received.[266][267] It was followed by a sequel, Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem (2007), the least financially-successful and worst-reviewed film in either franchise.[268]

Ridley Scott returned to the series for Prometheus (2012) (a prequel to Alien) and its sequel, Alien: Covenant (2017).[269] A fourth Alien sequel was in development by 2020, but was canceled by the Walt Disney Company following its acquisition of 20th Century Fox.[270][271] A stand-alone film in the Alien franchise, Alien: Romulus, was released on August 16, 2024; it is set between the events of Alien and Aliens.[272][273][274]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ As depicted in Alien (1979).

- ^ The exomoon known as LV-426 is also referred to as Acheron.[8]

- ^ Aliens' 1986 budget of $18.5 million is equivalent to $51.4 million in 2023.

- ^ Aliens' 1986 United States and Canada box office gross of $85.1 million is equivalent to $237 million in 2023.

- ^ According to different sources, Aliens' 1986 box office gross outside of the U.S. and Canada of $45.9 million to $98.1 million is equivalent to $128 million to $273 million in 2023.

- ^ Based on available figures, Aliens' 1986 worldwide box office gross of $131.1 million to $183.3 million is equivalent to $364 million to $510 million in 2023.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[2][3][4][5][6][7]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[10][45][46][48]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[34][38][57][58][59]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[166][169][170]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[173][174][175][176][177][178][179][180][181]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[138][211][212][213]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[222][223][224][225][226][227][228][229][230][231]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[232][233][234][235][236][237][238][239][240]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[241][242][243][244][245][246]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[2][3][4][5][6][7]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Aliens (1986)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c Errico, Marcus (February 27, 2017). "'Game Over, Man!': A Mini Oral History Of Bill Paxton's Classic Aliens Freakout". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on October 9, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ a b c Thrift, Matthew (July 2, 2015). "10 Best Action Movies". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on October 31, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c Cumbow, Robert C. (August 3, 2011). "Summer Of '86: James Cameron's Aliens". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on March 23, 2022. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ a b c Brew, Simon (August 13, 2009). "The 25 Best Blockbuster Sequels Of All Time". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Charisma, James (March 15, 2016). "Revenge of the Movie: 15 Sequels That Are Way Better Than The Originals". Playboy. Archived from the original on July 26, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ a b Valero, Geraldo (August 10, 2020). "Why Aliens Is Even Better Than Alien". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on August 12, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Williams, Stephanie (February 25, 2020). "Aliens' Newt Is More Than Someone To Be Saved". Syfy. Archived from the original on March 16, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Goodman, Walter (July 18, 1986). "Film: Sigourney Weaver In Aliens". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Aliens: The Colonial Marines". Empire. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Aliens: The Colonial Marines". Empire. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Witherow, Tim (April 22, 2016). "Where Are They Now? The Cast Of Aliens". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on February 26, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Collis, Clark (May 19, 2015). "Bill Paxton Talks Alien Reboot: 'You've Got To Have Hudson!'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Aliens: The Colonial Marines". Empire. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ Bartlett, Rhett (September 24, 2018). "Al Matthews, Cigar-Chomping Sgt. Apone In Aliens, Dies at 75". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 28, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (September 24, 2018). "RIP Al Matthews: As Sgt. Apone, He Fought To The End In Aliens". CNET. Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Winston, Matt (September 5, 2013). "Aliens – Chestburster Behind-the-scenes With Film Director And Fx Designer Stephen Norrington". Stan Winston School of Character Arts. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ Martin, Michileen (August 24, 1986). "Alien Actors You May Not Know Passed Away". Looper. Archived from the original on July 30, 2022. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ a b Beresford, Jack (May 14, 2017). "20 Deleted Scenes From The Alien Movies That Changed Everything". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ Weiss, Josh (April 7, 2020). "Jay Benedict, Aliens And Dark Knight Rises Actor, Dies at 68 From Coronavirus Complications". Syfy. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ "Aliens Actor Jay Benedict Dies After Contracting Covid-19". Calgary Herald. World Entertainment News Network. April 6, 2020. Archived from the original on November 21, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ Gallardo & Smith 2004, p. 68.

- ^ a b Miska, Brad (May 10, 2019). "Neca Steals 'Alien' Day Showcase With Newt Action Figure!". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on April 2, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- ^ Pickavance, Mark (August 13, 2017). "Whatever Happened To Carrie Henn?". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c Patrizio, Andy (November 11, 2003). "Aliens – Collector's Widescreen Edition DVD Review". IGN. Archived from the original on June 22, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ Ellard, Andrew (December 1, 2000). "Mr Flibble Talks To... Mac MacDonald". Red Dwarf. Archived from the original on May 5, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Leane, Rob (May 8, 2017). "River Of Pain: What It Adds to the Story Of Aliens". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ^ Oldershaw, Lauren (January 9, 2017). "History: Colchester Is Not Alien To A-lister Sigourney Weaver...Her Actress Mum Was Born Here". Daily Gazette. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ Gray, Tim (August 12, 2016). "Alan Ladd Jr. Documentary Proves There's Life Beyond The Original 'Star Wars'". Variety. Archived from the original on June 2, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Thurman, Trace (April 26, 2016). "[Aliens 30th Anniversary] Here's Why Aliens Almost Never Happened". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Friendly, David T. (July 24, 1986). "Aliens: A Battle-Scarred Trek into Orbit". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c Schickel, Richard. "Help! They're Back! (Page 3)". Time. Archived from the original on October 31, 2007. Retrieved November 10, 2020.