Living in the Material World

| Living in the Material World | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 30 May 1973 | |||

| Recorded |

| |||

| Studio | ||||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 43:55 | |||

| Label | Apple | |||

| Producer | George Harrison (with Phil Spector on "Try Some, Buy Some") | |||

| George Harrison chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Living in the Material World | ||||

| ||||

Living in the Material World is the fourth studio album by the English musician George Harrison, released in 1973 on Apple Records. As the follow-up to 1970's critically acclaimed All Things Must Pass and his pioneering charity project, the Concert for Bangladesh, it was among the most highly anticipated releases of that year. The album was certified gold by the Recording Industry Association of America two days after release, on its way to becoming Harrison's second number 1 album in the United States, and produced the international hit "Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)". It also topped albums charts in Canada and Australia, and reached number 2 in Britain.

Living in the Material World is notable for the uncompromising lyrical content of its songs, reflecting Harrison's struggle for spiritual enlightenment against his status as a superstar, as well as for what many commentators consider to be the finest guitar and vocal performances of his career. In contrast with All Things Must Pass, Harrison scaled down the production for Material World, using a core group of musicians comprising Nicky Hopkins, Gary Wright, Klaus Voormann and Jim Keltner. Ringo Starr, John Barham and Indian classical musician Zakir Hussain were among the album's other contributors.

Upon release, Rolling Stone described it as a "pop classic", a work that "stands alone as an article of faith, miraculous in its radiance".[1] Most contemporary reviewers consider Living in the Material World to be a worthy successor to All Things Must Pass, even if it inevitably falls short of Harrison's grand opus. Author Simon Leng refers to the album as a "forgotten blockbuster", representing "the close of an age, the last offering of the Beatles' London era".[2] EMI reissued the album in 2006, in remastered form with bonus tracks, and released a deluxe-edition CD/DVD set that included film clips of four songs. A newly remixed and expanded edition was released in 2024 to celebrate its 50th anniversary.

Background

[edit]I wouldn't really care if no one ever heard of me again. I just want to play and make records and work on musical ideas.[3]

– Harrison to Record Mirror in April 1972, during his year away from the public eye after the Concert for Bangladesh

George Harrison's 1971–72 humanitarian aid project for the new nation of Bangladesh had left him an international hero,[4][5][6] but also exhausted and frustrated in his efforts to ensure that the money raised would find its way to those in need.[7][8] Rather than record a follow-up to his acclaimed 1970 triple album, All Things Must Pass, Harrison put his solo career on hold for over a year following the two Concert for Bangladesh shows,[9][10] held at Madison Square Garden, New York, in August 1971.[11] In an interview with Disc and Music Echo magazine in December that year, pianist Nicky Hopkins spoke of having just attended the New York sessions for John Lennon's "Happy Xmas (War Is Over)" single, where Harrison had played them "about two or three hours" worth of new songs, adding: "They were really incredible."[12] Hopkins suggested that work on Harrison's next solo album was to begin in January or February at his new home studio at Friar Park,[12] but any such plan was undone by Harrison's commitment to the Bangladesh relief project.[13][nb 1] While he found time during the last few months of 1971 to produce singles for Ringo Starr and Apple Records protégés Lon & Derrek Van Eaton, and to help promote the Ravi Shankar documentary Raga,[18][19] Harrison's next project in the role of music producer was not until August 1972, when Cilla Black recorded his composition "When Every Song Is Sung".[20]

Throughout this period, Harrison's devotion to Hindu spirituality – particularly to Krishna consciousness via his friendship with A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada[21] – reached new heights.[22][23] As Harrison admitted, his adherence to his spiritual path was not necessarily consistent.[24][25] His wife, Pattie Boyd, and their friend Chris O'Dell would joke that it was hard to tell whether he was dipping into his ever-present Japa Yoga prayer bag or "the coke bag".[26] This duality has been noted by Harrison biographers Simon Leng and Alan Clayson: on one hand, Harrison earned himself the nickname "His Lectureship" during his prolonged periods of fervid devotion;[27] on the other, he participated in bawdy London sessions for the likes of Bobby Keys' eponymous solo album and what Leng terms Harry Nilsson's "thoroughly nasty" "You're Breakin' My Heart", both recorded in the first half of 1972.[19][28] Similarly, Harrison's passion for high-performance cars saw him lose his driving licence for the second time in a year after crashing his Mercedes into a roundabout at 90 miles an hour, on 28 February, with Boyd in the passenger seat.[29][30][nb 2]

In August 1972, with the Concert for Bangladesh documentary film having finally been released worldwide, Harrison set off alone for a driving holiday in Europe,[15] during which he chanted the Hare Krishna mantra nonstop for a whole day, he later claimed.[32][33] Religious academic Joshua Greene, a Hare Krishna devotee, has described this trip as Harrison's "preparation" for recording the Living in the Material World album.[33][nb 3]

Songs

[edit]Rather than revisit compositions left over from the All Things Must Pass sessions, Harrison's material for Living in the Material World was drawn from the 1971–72 period,[38] with the exception of "Try Some, Buy Some", which he wrote in 1970 and recorded with former Ronette Ronnie Spector in February 1971.[39] The songs reflected his spiritual devotion[40] – in the case of "The Lord Loves the One (That Loves the Lord)", "Living in the Material World", "Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)" and "Try Some, Buy Some"[41][42] – as well as his feelings before and after the Bangladesh benefit concerts, with "The Day the World Gets 'Round" (and the non-LP single B-side "Miss O'Dell").[43]

Both "The Lord Loves the One" and the album's title track were directly inspired by Prabhupada's teachings.[44][45] Greene writes of Harrison adapting a passage from the Bhagavad Gita into his lyrics for "Living in the Material World" and adds: "Some of the songs distilled spiritual concepts into phrases so elegant they resembled Vedic sutras: short codes that contain volumes of meaning."[46] On "Give Me Love", Harrison blended the Hindu bhajan style (or devotional song) with Western gospel music, repeating the formula of his 1970–71 international hit "My Sweet Lord".[47] In his 1980 autobiography, I Me Mine, he describes the song as "a prayer and personal statement between me, the Lord, and whoever likes it".[48]

Whereas Harrison's Krishna devotionals on All Things Must Pass had been uplifting celebrations of faith,[49] his latest compositions betrayed a more austere quality,[50] partly as a result of the Bangladesh experience.[51] His musical arranger, John Barham, would later suggest that a spiritual "crisis" might have been the cause;[50] other observers have pointed to Harrison's failing marriage to Boyd.[14][52][nb 4] Leng writes of his frame of mind at this time: "while George Harrison was bursting with musical confidence, Living in the Material World found him in roughly the same place that John Lennon was when he wrote 'Help!' – shocked by the rush of overwhelming success and desperately wondering where it left him."[54]

All Things Must Pass might be better, but those songs [on Living in the Material World] are incredible … You can hear from the LP what his aim was; he definitely had a message he wanted to get across.[50]

– Klaus Voormann, 2003

Other song themes addressed the Beatles' legacy,[55] either in direct references to the band's history – in the case of "Living in the Material World" and "Sue Me, Sue You Blues"[56][57] – or in Harrison's stated desire to live in the present, free of his former identity, in the case of "The Light That Has Lighted the World", "Who Can See It" and "Be Here Now".[58] The lyrics to "Who Can See It" reflect Harrison's disenchantment with his previous, junior status to former bandmates Lennon and Paul McCartney,[59] while "Sue Me, Sue You Blues" was his comment on McCartney's 1971 High Court action to dissolve the band as a business entity.[60] In line with Prabhupada's teachings, all such pursuits of fame, wealth or position meant nothing in Harrison's 1972 world-view.[61] Author Gary Tillery writes of Material World's lyrical content: "The album expresses his impressions of the mundane and the spiritual worlds and the importance of ignoring the lures of the everyday world and remaining focused on the eternal verities."[62] Even in seemingly conventional love songs such as "That Is All" and "Don't Let Me Wait Too Long",[63] Harrison appeared to be addressing his deity as much as any human partner.[64] Musically, the latter composition reflects the influence of Brill Building songwriters of the early 1960s,[65] while Harrison sings of a love delivered "like it came from above".[55]

Harrison donated his copyright for nine of the eleven songs on Living in the Material World, together with the non-album B-side "Miss O'Dell",[66] to his Material World Charitable Foundation.[67][nb 5] The latter initiative was set up in reaction to the tax issues that had hindered his relief effort for the Bangladeshi refugees,[68][70] and ensured a perpetual stream of income, through ongoing publishing royalties, for dispersal to the charities of his choice.[71]

Production

[edit]Phil was never there … I'd go along the roof at The Inn on the Park [hotel] in London and climb in his window yelling, "Come on! We're supposed to be making a record." … [Then] he used to have eighteen cherry brandies before he could get himself down to the studio.[72]

– Harrison discussing Phil Spector's early involvement on the album

After the grand, Wall of Sound production of All Things Must Pass,[73] Harrison wanted a more understated sound this time around, to "liberate" the songs, as he later put it.[74][75] He had intended to co-produce with Phil Spector as before,[76] although the latter's erratic behaviour and alcohol consumption[77] ensured that, once sessions were under way in October 1972, Harrison was the project's sole producer.[78] Spector received a credit for "Try Some, Buy Some", however,[79] since Harrison used the same 1971 recording, featuring musicians such as Leon Russell, Jim Gordon, Pete Ham and Barham,[80] that they had made for Ronnie Spector's abandoned solo album.[81]

A release date was planned for January or February 1973, with the album title rumoured to be The Light That Has Lighted the World.[76] Within a month, the title was announced as The Magic Is Here Again,[82][83] with an erroneous report in Rolling Stone magazine claiming that Eric Clapton was co-producing and that the album was set for release on 20 December 1972.[78]

Recording

[edit]In another contrast with his 1970 triple album, Harrison engaged a small core group of musicians to support him on Living in the Material World.[84][85] Gary Wright, who shared Harrison's spiritual preoccupations,[86] and Klaus Voormann returned, on keyboards and bass, respectively, and John Barham again provided orchestral arrangements.[78] They were joined by Jim Keltner, who had impressed at the 1971 Bangladesh concerts,[87] and Nicky Hopkins,[78] whose musical link to Harrison went back to the 1968 Jackie Lomax single "Sour Milk Sea".[85] Ringo Starr also contributed to the album, when his burgeoning film career allowed,[88] and Jim Horn, another musician from the Concert for Bangladesh band, supplied horns and flutes.[78] The recording engineer was Phil McDonald, who had worked in the same role on All Things Must Pass.[89]

All the rhythm and lead guitar parts were performed by Harrison alone[90] – the ex-Beatle stepping out from the "looming shadow" of Clapton for the first time, Leng has noted.[91] Most of the basic tracks were recorded with Harrison on acoustic guitar; only "Living in the Material World", "Who Can See It" and "That Is All" featured electric rhythm parts, those for the latter two songs adopting the same Leslie-toned sound found on much of the Beatles' Abbey Road (1969).[59][92] Ham and his Badfinger bandmate Tom Evans augmented the line-up on 4 and 11 October,[38] although their playing would not find its way onto the released album.[93]

The sessions took place partly at Apple Studios in London, but mostly at Harrison's home studio, FPSHOT, according to Voormann.[78][94][nb 6] Apple Studios, together with its Savile Row, London W1 address, received a prominent credit on the Living in the Material World record sleeve, as a further sign of Harrison's championing of the Beatles-owned recording facility.[94][98] At the weekends during these autumn months, Hopkins recorded his own solo album, The Tin Man Was a Dreamer (1973), at Apple,[85] with contributions from Harrison, Voormann and Horn.[99][100] Voormann has described the mood at the Friar Park sessions as "intimate, quiet, friendly" and in stark contrast to the sessions he, Harrison and Hopkins had attended at Lennon's home in 1971, for the Imagine album.[96] Keltner recalls Harrison as having been focused and "at his peak physically" throughout the recording of Living in the Material World,[86] having given up smoking and taken to using Hindu prayer beads.[101]

The sessions continued until the end of November,[78] when Hopkins left for Jamaica to work on the Rolling Stones' new album.[102] During this period, Harrison co-produced a new live album for Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan for a January release on Apple Records,[103] the highly regarded In Concert 1972.[104][nb 7]

Overdubbing and mixing

[edit]After hosting a visit by Bob Dylan and his wife Sara at Friar Park,[106] Harrison resumed work on the album in January 1973, at Apple.[107] "Sue Me, Sue You Blues", which he had originally given to Jesse Ed Davis to record in 1971,[38] was taped at this point.[108] The lyrics' courtroom theme had a new relevance in early 1973,[109] as he, Lennon and Starr looked to sever all legal ties with manager Allen Klein, who had been the prime cause for McCartney's earlier litigation.[110][nb 8]

For the rest of January and through February, extensive overdubs were carried out on the album's basic tracks[76] – comprising vocals, percussion, Harrison's slide guitar parts and Horn's contributions. "Living in the Material World" received significant attention during this last phase of the album production, with sitar, flute and Zakir Hussain's tabla being added to fill the song's two "spiritual sky" sections.[78][nb 9] The resulting contrast between the main, Western rock portion and the Indian-style middle eights emphasised Harrison's struggle between physical-world temptations and his spiritual goals.[115][116] The Indian instrumentation overdubbed on this track and "Be Here Now" also marked a rare return to the genre for Harrison,[117] recalling his work with the Beatles over 1966–68 and his first solo album, Wonderwall Music (1968).[118]

Barham's orchestra and choir were the final items to be recorded, on "The Day the World Gets 'Round", "Who Can See It" and "That Is All",[119] in early March.[78] With production on the album completed, Harrison flew to Los Angeles for Beatles-related business meetings[120] and to begin work on Shankar and Starr's respective albums, Shankar Family & Friends (1974) and Ringo (1973).[54]

Album artwork

[edit]

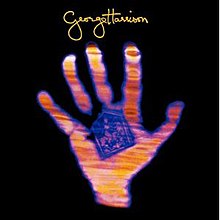

As he had done with All Things Must Pass and The Concert for Bangladesh, Harrison entrusted the album's art design to Tom Wilkes,[121] and the latter's new business partner, Craig Baun.[122][123] The gatefold and lyric insert sleeves for Living in the Material World were much commented-on at the time of release, Stephen Holden of Rolling Stone describing the record as "beautifully-packaged with symbolic hand-print covers and the dedication, 'All Glories to Sri Krsna'",[1] while author Nicholas Schaffner likewise admired the "color representations of the Hindu scriptures",[82] in the form of a painting from a Prabhupada-published edition of the Bhagavad Gita.[74][124] Reproduced on the lyric insert sheet (on the back of which was a red Om symbol with yellow surround), this painting features Krishna with Arjuna, the legendary archer and warrior, in a chariot, being pulled by the enchanted seven-headed horse Uchchaihshravas.[121] With the album arriving at the height of the glam or glitter rock musical trend,[125] Clayson writes of this image: "a British teenager might have still dug the gear worn by Krishna in his chariot … Androgynous in beaded kaftan, jewelled fez and peacock feather, and strikingly pretty, the Supreme Personality of Godhead was not unlike some of the new breed of theatrical British chartbusters."[126]

For the album's striking front-cover image, Wilkes used a Kirlian photograph of Harrison's hand holding a Hindu medallion.[127] The photo was taken at UCLA's parapsychology department, as was the shot used on the back cover, where Harrison instead holds three US coins: a couple of quarters and a silver dollar.[121]

The gatefold's inner left panel, opposite the album's production credits, showed Harrison and his fellow musicians – Starr, Horn, Voormann, Hopkins, Keltner and Wright – at a long table, laden with food and wine.[121][128] A deliberate parody of Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper,[129] the picture was taken in California at the mock-Tudor home of entertainment lawyer Abe Somer, by Hollywood glamour photographer Ken Marcus.[121][nb 10] As with the US coinage used on the back cover, various details in the photo represent what Harrison termed the "gross" aspects[130] of life in the material world.[121] Clayson has speculated about the symbolism and hidden messages within the photo: whether the nurse with a pram, set back from and to the left of the table, was a reference to Boyd's inability to conceive a child; and the empty, distant wheelchair in memory of Harrison's late mother.[128] New Testament scholar Dale Allison observes the anti-Catholic sentiment within this inner-gatefold photo, following on from Harrison's lyrics to his 1970 song "Awaiting on You All".[129] Harrison is dressed as a priest, all in black, sporting an Old West six-shooter – "a slam at the perceived materialism and violence of the Roman church", Allison writes.[129]

On the back cover, underneath the second hand-print design, text provides details of the fictitious Jim Keltner Fan Club,[131] information on which was available by sending a "stamped undressed elephant" – for: self-addressed envelope – to a Los Angeles postal address. This detail was an affectionate thank-you to the popular drummer (Starr would repeat the gesture on his album later in the year), as well as a light-hearted dig – in its use of "wing" symbols, like those in Wings' logo – at McCartney, who had recently launched a fan club for his new band.[121][131]

Release

[edit]

Due to the extended recording period, Living in the Material World was issued at the end of a busy Apple release schedule, with April and May 1973 having already been set aside for the Beatles compilations 1962–1966 and 1967–1970 and for Paul McCartney & Wings' second album, Red Rose Speedway.[131][132] Schaffner recorded in his book The Beatles Forever: "For a while there ... album charts were reminiscent of the golden age of Beatlemania."[133] Preceding Harrison's long-awaited release was the acoustic single "Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)",[134] which became his second number 1 hit in the United States.[135] This was accompanied by a billboard and print advertising campaign,[136][137] including a three-panel poster combining the album's front and back covers, and an Apple publicity photo showing Harrison, now free of the heavy beard familiar from the All Things Must Pass–Concert for Bangladesh era,[138] with his hand outstretched, mirroring Wilkes' album cover image.[133][139]

Living in the Material World was issued on 30 May 1973 in America (with Apple catalogue number SMAS 3410) and on 22 June in Britain (as Apple PAS 10006).[140] It enjoyed immediate commercial success,[141] entering the Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart at number 11 and hitting number 1 in its second week, on 23 June, demoting Wings' album in the process.[142] Material World spent five weeks atop the US charts, having been awarded a gold disc by the RIAA selling more than 500,000 copies within two days of release based on advance orders.[143][144] Global US sales of the album stand at almost 1 million copies. Nonetheless, despite such high initial sales, the record's follow-on success was limited by what Leng terms the "anomalous" decision to cancel the release of a second US single, "Don't Let Me Wait Too Long".[145]

In the UK, the album peaked at number 2, held from the top position by the soundtrack to Starr's film That'll Be the Day.[146] Material World also topped albums charts in Australia[147] and Canada.[148] In January 1975, the Canadian Recording Industry Association announced that it had been certified as a gold album.[149][nb 11]

With Living in the Material World, Harrison achieved the Billboard double for a second time when "Give Me Love" hit the top position during the album's stay at number 1[74] – the only one of his former bandmates to have done it even once being McCartney, with the recent "My Love" and Red Rose Speedway.[144][151] Harrison carried out no supporting promotion for Material World; "pre-recorded tapes" were issued to BBC Radio 1 and played repeatedly on the show Radio One Club, but his only public appearance in Britain was to accompany Prabhupada on a religious procession through central London, on 8 July.[152] According to author Bill Harry, the album sold over 3 million copies worldwide.[153]

Critical reception

[edit]Contemporary reviews

[edit]Leng describes Living in the Material World as "one of the most keenly anticipated discs of the decade" and its unveiling "a major event".[154] Among expectant music critics, Stephen Holden began his highly favourable[115][155] review in Rolling Stone with the words "At last it's here", before hailing the new Harrison album as a "pop classic" and a "profoundly seductive record".[1] "Happily, the album is not just a commercial event," he wrote, "it is the most concise, universally conceived work by a former Beatle since John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band."[1] Billboard magazine noted the twin themes found throughout the album – "the Beatles and their mish-mash" versus a "spiritual undercoat" – and described Harrison's vocals as "first-rate".[156]

Living in the Material World is a profoundly seductive record. Harrison's rapt dedication infuses his musicality so completely that the album stands alone as an article of faith, miraculous in its radiance.[1]

– Stephen Holden in Rolling Stone, June 1973

Two weeks ahead of the UK release date, Melody Maker published a full-page "exclusive preview" of Material World by its New York correspondent, Michael Watts.[157] The latter wrote that "the most strikingly immediate impression left by the album" concerned its lyrics, which, although "solemn and pious" at times, were "more interesting" thematically than those on All Things Must Pass, such that Material World was "as personal, in its own way, as anything that Lennon has done".[158] While describing the pared-down production as "good artistic judgement in view of the nature of the lyrics", Watts concluded: "Harrison has always struck me before as simply a writer of very classy pop songs; now he stands as something more than an entertainer. Now he's being honest."[158]

While Holden had opined that, of all the four Beatles, Harrison had inherited "the most precious" legacy – namely, "the spiritual aura that the group accumulated, beginning with the White Album"[1] – other reviewers objected to the overt religiosity of Living in the Material World.[159][160] This was particularly so in Britain,[86][128] where by summer 1973, author Bob Woffinden later wrote, "the Beatle bubble had undoubtedly burst" and for each of the former bandmates, his individual "pedestal" was now "an exposed, rather than a comfortable, place to be".[161]

It’s also breathtakingly unoriginal and – lyrically at least – turgid, repetitive and so damn holy I could scream.[162]

– Tony Tyler, reviewing the album for NME

In the NME, Tony Tyler began his review by stating that he had long idolised Harrison as "the finest packaged object since frozen pizza", but he had changed his opinion dramatically in recent years; after the "dire, ennui-making" All Things Must Pass, Tyler continued, "the unworthiness of my heretical thoughts smote home around the time of the Bangla Desh concerts."[163] Tyler dismissed Material World with the description: "[It's] pleasant, competent, vaguely dull and inoffensive. It’s also breathtakingly unoriginal and – lyrically at least – turgid, repetitive and so damn holy I could scream."[163] The reviewer concluded: "I have no doubt whatever it'll sell like hot tracts and that George'll donate all the profits to starving Bengalis and make me feel like the cynical heel I undoubtedly am."[162][163] Robert Christgau was also unimpressed in Creem, giving the record a "C" grade and writing that "Harrison sings as if he's doing sitar impressions".[164] In their 1975 book The Beatles: An Illustrated Record, Tyler and co-author Roy Carr bemoaned Harrison's "didactically imposing said Holy Memoirs upon innocent record-collectors" and declared the album's spiritual theme "almost as offensive in its own way" as Lennon and Yoko Ono's political radicalism on Some Time in New York City (1972).[165]

They feel threatened when you talk about something that isn't just "be-bop-a-lula". And if you say the words "God" or "Lord", it makes some people's hair curl.[128]

– Harrison to Melody Maker in September 1971, pre-empting criticism of his lyrics on Material World[159]

Writing in the inaugural issue of the Australian publication Ear for Music, Anthony O'Grady remarked on the album's religiosity: "oftentimes the music is a more truthful guide to the sense of the lyrics than the words themselves. Harrison is not a great wordsmith but he is a superb musician. Everything flows, everything interweaves. His melodies are so superb they take care of everything."[166] Like Holden, Nicholas Schaffner approved of the singer's gesture in donating his publishing royalties to the Material World Charitable Foundation and praised the album's "exquisite musical underpinnings".[82] Although the "transcendent dogma" was not always to his taste, Schaffner recognised that in Living in the Material World, Harrison had "devised a luxuriant rock devotional designed to transform his fans' stereo equipment into a temple".[167]

Aside from the album's lyrical themes, its production and musicianship were widely praised, Schaffner noting: "Surely Phil Spector never had a more attentive pupil."[67] Carr and Tyler lauded Harrison's "superb and accomplished slide-guitar breaks",[165] and the solos on "Give Me Love", "The Lord Loves the One", "The Light That Has Lighted the World" and "Living in the Material World" have each been identified as exemplary and among the finest of Harrison's career.[90][91][168][169] In his book The Beatles Apart (1981), Woffinden wrote: "Those who carped at the lyrics, or at Harrison himself, missed a great deal of the music, much of which was exceptionally fine."[79] Woffinden described the album as "a very good one", Harrison's "only mistake" being that he had waited so long before following up his successes over 1970–71.[170]

Retrospective assessment

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Classic Rock | 8/10[172] |

| Mojo | |

| The Music Box | |

| MusicHound Rock | 3.5/5[175] |

| Music Story | |

| OndaRock | 7/10[177] |

| PopMatters | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

In the decades following its release, Living in the Material World gained a reputation as "a forgotten blockbuster" – a term used by Simon Leng[22] and echoed by commentators such as Robert Rodriguez[180] and AllMusic's Bruce Eder.[90] The latter describes Harrison's 1973 album as "an underrated minor masterpiece" that "represent[s] his solo playing and songwriting at something of a peak".[90] John Metzger of The Music Box refers to Material World as "the most underrated and overlooked album of [Harrison]'s career", adding that it "coalesces around its songs … and the Zen-like beauty that emanates from Harrison's hymns to a higher power inevitably becomes subtly affecting."[174]

Writing in Rolling Stone in 2002, Greg Kot found the album "drearily monochromatic" compared to its predecessor,[181] and to PopMatters' Zeth Lundy, it suffers from "a more anonymous tract" next to the "cathedral-grade significance" of All Things Must Pass.[178] Reviewing Harrison's solo career for Goldmine magazine in 2002, Dave Thompson considered the 1973 album to be the equal of All Things Must Pass, reasoning: "While history insists that Living in the Material World could not help but be eclipsed by its gargantuan forebear, with the two albums in the CD player and the 'shuffle' function mixing them up, it's difficult to play favourites."[182]

In his review of the 2006 remastered release, for Q magazine, Tom Doyle praised the album's ballads, such as "The Light That Has Lighted the World" and "Be Here Now", and suggested that "the distance of time helps to reveal its varied charms".[183] Mojo's Mat Snow wrote of "this long overdue reissue" being "worth it alone for four wonderful songs", including "Don't Let Me Wait Too Long" and "The Day the World Gets 'Round", and concluded: "The rest is Hari Georgeson at his most preachy, but it's never less than musical and often light on its feet."[173] In another 2006 review, for the Vintage Rock website, Shawn Perry wrote of Material World being "more restrained and immediate without the wall of sound whitewash of its predecessor, but its flow and elegance are unmistakable". Perry admired Harrison's slide guitar playing and rated the album an "underrated, classic record".[184] Writing for Uncut in 2008, David Cavanagh described Material World as "a bit full-on, religion-wise" but "the album to play if you want musicianship at its best".[185]

Living in the Material World was listed as the fifth best Beatles solo album by Paste in 2012.[186] In their similar lists, Ultimate Classic Rock ranks it at number 7[187] and The Independent at number 6.[188]

2014 appraisal and legacy

[edit]Reviewing the 2014 reissue, Blogcritics' Chaz Lipp writes that "this chart-topping classic is, in terms of production, arguably preferable to its predecessor", adding: "The sinewy 'Sue Me, Sue You Blues,' galloping title track, and soaring 'Don't Let Me Wait Too Long' rank right alongside Harrison's best work."[189] Alex Franquelli of PopMatters refers to it as "a worthy successor" to All Things Must Pass and an album that "raises the bar of social awareness that had only been touched on lightly in the previous release". Franquelli concludes: "It is a work that enjoys a more elaborate dynamic development, where layers are kept together by Harrison’s clever work behind the mixing desk."[190] In another 2014 review, for Classic Rock, Paul Trynka writes: "All these years on, it's his most overtly spiritual album that sparkles today … The well-known songs, such as 'Sue Me, Sue You Blues' (dedicated to the rapacious Allen Klein), stand up well, but it's the more restrained tracks – 'Don't Let Me Wait Too Long', 'Who Can See It' – that entrance: gorgeous pop songs, all the more forceful for their restraint." Trynka goes on to describe "Be Here Now" as the album's "towering achievement" and "a masterpiece".[191][192]

Among Beatles biographers, Alan Clayson approves of Material World's "self-production criterion closer to the style of George Martin", after the "looser abundance" of All Things Must Pass.[193] Within the more restrained surroundings, Clayson adds, Harrison laid claim to the title "king of rock 'n' roll slide guitar", in addition to giving perhaps his "most magnificent [vocal] performance on record" on "Who Can See It".[168] Rodriguez also approves of a production aesthetic that allows instruments to "sparkle" and "breathing space" for his melodies, and rates Harrison's guitar playing as "stellar" throughout.[194] Peter Lavezzoli describes the album as "a soulful collection of songs that feature some of Harrison's finest singing, particularly the gorgeous Roy Orbison-esque ballad 'Who Can See It'".[160]

Leng has named Living in the Material World as his personal favourite of all of Harrison's solo albums.[195] According to Leng, with its combination of a defiant "protest" song in "The Day the World Gets 'Round", the anti-stardom "The Lord Loves the One", and "perfect pop confections" in "Give Me Love" and "Don't Let Me Wait Too Long", Living in the Material World was the last album to capture the same clear-sighted, utopian spirit that characterised the 1960s.[196] Eder likewise welcomes Material World's bold idealism, saying: "Even in the summer of 1973, after years of war and strife and disillusionment, some of us were still sort of looking – to borrow a phrase from a Lennon–McCartney song – or hoping to get from them something like 'the word' that would make us free. And George, God love him, had the temerity to actually oblige ..."[90]

Reissues

[edit]2006

[edit]While solo works by Lennon, McCartney and Starr had all been remastered as part of repackaging campaigns during the 1990s and early 21st century, Harrison's Living in the Material World was "neglected over the years", author Bruce Spizer wrote in 2005, an "unfortunate" situation considering the quality of its songs.[78] On 25 September 2006, EMI reissued the album in the UK, on CD and in a deluxe CD/DVD package,[197] with Capitol Records' US release following the next day.[198] The remastered Material World featured two additional tracks,[199] neither of which had previously been available on an album:[200] "Deep Blue" and "Miss O'Dell", popular B-sides, respectively, to the 1971 non-album single "Bangla Desh" and "Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)".[178] The CD/DVD edition contained a 40-page full colour booklet[197] that included extra photos from the inner-gatefold shoot (taken by Mal Evans and Barry Feinstein), liner notes by Kevin Howlett, and Harrison's handwritten lyrics and comments on the songs, reproduced from I Me Mine.[201]

The DVD featured a concert performance of "Give Me Love", recorded during Harrison's 1991 Japanese tour with Eric Clapton,[198] and previously unreleased versions of "Miss O'Dell" and "Sue Me, Sue You Blues" set to a slideshow of archival film.[197] The final selection consisted of the album's title track playing over 1973 footage[197] of the LP being audio-tested and packaged prior to shipment.[174] While Zeth Lundy found that the deluxe edition "bestows lavish attention upon a record that may not exactly deserve it", with the DVD "an unnecessary bonus",[178] Shawn Perry considered the supplementary disc to be possibly the "pièce de résistance" of the 2006 reissue, and concluded: "this package is a beautiful tribute to the late and great guitarist any Beatles and Harrison fan will cherish."[184]

2014

[edit]Living in the Material World was remastered again for inclusion in the Harrison box set The Apple Years 1968–75, issued in September 2014.[202] Also available as a separate CD, the reissue reproduces Howlett's 2006 essay and adds "Bangla Desh" as a third bonus track, after "Deep Blue" and "Miss O'Dell".[203] In his preview of the 2014 reissues, for Rolling Stone, David Fricke pairs Material World with All Things Must Pass as representing "the heart of the [box] set".[204] Disc eight of The Apple Years includes the four items featured on the 2006 deluxe edition DVD.[203]

2024

[edit]| 50th anniversary reissue | |

|---|---|

| Aggregate scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 92/100[205] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Clash | 8/10[206] |

| Rolling Stone | |

To celebrate its 50th anniversary, Living in the Material World was reissued as an expanded super deluxe box set on 15 November 2024. It features a newly remixed version of the original album, early takes, and a 60-page hardcover book curated by Olivia Harrison and Rachel Cooper. Physical editions include a 7" single containing a previously unheard rendition of "Sunshine Life for Me (Sail Away Raymond)", featuring members of the Band (Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm, Garth Hudson and Rick Danko) and Ringo Starr.[208][209] Beatles author Kenneth Womack praised the remixed version as "affording the recordings with greater definition while being assiduously careful about maintaining the artist's five-decade-old vision".[210] In a four-star review for Rolling Stone, Rob Sheffield called the album Harrison's "most profoundly weird" but a "slept-on masterpiece" that gets a "long-overdue appreciation" with the 50th anniversary reissue.[207]

Track listing

[edit]All songs written by George Harrison.

Original release

[edit]Side one

- "Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)" – 3:36

- "Sue Me, Sue You Blues" – 4:48

- "The Light That Has Lighted the World" – 3:31

- "Don't Let Me Wait Too Long" – 2:57

- "Who Can See It" – 3:52

- "Living in the Material World" – 5:31

Side two

- "The Lord Loves the One (That Loves the Lord)" – 4:34

- "Be Here Now" – 4:09

- "Try Some, Buy Some" – 4:08

- "The Day the World Gets 'Round" – 2:53

- "That Is All" – 3:43

2006 remaster

[edit]Tracks 1–11 as per the original release, with the following bonus tracks:

- "Deep Blue" – 3:47

- "Miss O'Dell" – 2:33

Deluxe edition DVD

- "Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)" (recorded live at Tokyo Dome on 15 December 1991)

- "Miss O'Dell" (alternative version)

- "Sue Me, Sue You Blues" (acoustic demo version)

- "Living in the Material World"

2014 remaster

[edit]Tracks 1–11 as per the original release, with the following bonus tracks:

- "Deep Blue" – 3:47

- "Miss O'Dell" – 2:33

- "Bangla Desh" – 3:57

Personnel

[edit]- George Harrison – lead and backing vocals, electric and acoustic guitars, dobro, sitar

- Nicky Hopkins – piano, electric piano

- Gary Wright – organ, harmonium, electric piano, harpsichord

- Klaus Voormann – bass guitar, standup bass, tenor saxophone

- Jim Keltner – drums, percussion

- Ringo Starr – drums, percussion

- Jim Horn – saxophones, flute, horn arrangement

- Zakir Hussain – tabla

- John Barham – orchestral and choral arrangements

- Leon Russell – piano (on "Try Some, Buy Some")

- Jim Gordon – drums, tambourine (on "Try Some, Buy Some")

- Pete Ham – acoustic guitar (on "Try Some, Buy Some")

Charts

[edit]Weekly charts

[edit]|

Original release

|

Reissues

|

Year-end charts

[edit]| Chart (1973) | Position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums Chart[233] | 24 |

| Dutch Albums Chart[234] | 39 |

| French Albums Chart[235] | 16 |

| US Billboard Year-End[236][237] | 43 |

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[238] | Gold | 35,000^ |

| Canada (Music Canada)[149] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[239] | Gold | 500,000^ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

Notes

[edit]- ^ Among activities that drained much of his creativity from September 1971 through to late 1972, Harrison was embroiled in negotiations with Capitol Records over the Concert for Bangladesh live album,[14] technical issues with the disappointing footage from the New York shows,[15][16] and transatlantic meetings with lawyers and various US and British government departments.[17]

- ^ Of the two of them, his wife suffered the most serious injuries,[29][30] her recovery from which, Clayson has noted, Harrison saw fit to assist by "pounding on a drum-kit that he'd set up in the next room" at Friar Park.[31]

- ^ Further aligning himself with the Hare Krishna movement, in early 1973,[34] Harrison purchased Piggott's Manor[35] in Hertfordshire for the growing number of UK-based devotees.[36] Renamed Bhaktivedanta Manor, the property remains ISKCON's main centre for study and worship in Britain.[37]

- ^ Harrison himself gave 1972 as the year he started writing "So Sad", a track dealing with the end of their relationship, later released on his Dark Horse album.[53]

- ^ The remaining songs were "Try Some, Buy Some" and "Sue Me, Sue You Blues",[68] both of which were 1971 copyrights that had already been assigned to their composer's publishing company, Harrisongs.[69]

- ^ The German bassist vividly recalls recording his part for "Be Here Now" in a toilet there,[95][96] and footage included in Martin Scorsese's 2011 Harrison documentary shows the musicians playing at Friar Park.[97]

- ^ In addition, Harrison produced an early version of his and Starr's co-composition "Photograph" sometime before Christmas.[105]

- ^ While he shared Lennon and Starr's general disillusion with their manager,[111] Harrison was especially aggrieved at Klein's handling of the Bangladesh relief effort.[112] Klein had neglected to register the 1971 concerts as charity fundraisers beforehand, resulting in the aid project being denied tax-exempt status.[113]

- ^ As revealed on the Living in the Alternate World bootleg, these sections had been taped with minimal instrumentation, awaiting the requisite musical colouring.[114]

- ^ Somer in fact took Wright's place in the shot, after which Wilkes superimposed a picture of the musician's face.[121]

- ^ Capitol Canada executives presented Harrison with the award, along with a CRIA platinum disc for All Things Must Pass, in Toronto in December 1974, shortly before he performed at the city's Maple Leaf Gardens.[150]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Stephen Holden, "George Harrison, Living in the Material World" Archived 3 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Rolling Stone, 19 July 1973, p. 54 (retrieved 12 April 2014).

- ^ Leng, pp. 124, 140.

- ^ Clayson, p. 318.

- ^ Schaffner, pp. 147, 159.

- ^ Leng, p. 121.

- ^ Tillery, p. 100.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 220.

- ^ Doggett, pp. 180–81, 192.

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 193–94.

- ^ Liner note essay by Kevin Howlett, The Apple Years 1968–75 book (Apple Records, 2014), p. 31.

- ^ Woffinden, pp. 48, 68.

- ^ a b Andrew Tyler, "Nicky Hopkins", Disc and Music Echo, 4 December 1971; available at Rock's Backpages Archived 24 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine (subscription required; retrieved 30 August 2012).

- ^ Leng, pp. 123–24.

- ^ a b The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 43.

- ^ a b Badman, p. 79.

- ^ George Harrison, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Doggett, p. 192.

- ^ Badman, pp. 54–56.

- ^ a b Leng, p. 123.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, pp. 439–40.

- ^ Allison, pp. 45–47.

- ^ a b Leng, p. 124.

- ^ Huntley, pp. 87, 89.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 254.

- ^ "George Harrison – In His Own Words" Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, superseventies.com (retrieved 8 April 2014).

- ^ O'Dell, p. 188.

- ^ Clayson, p. 330.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 293, 325.

- ^ a b Badman, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b Tillery, pp 118–19.

- ^ Clayson, p. 320.

- ^ Clayson, p. 248.

- ^ a b Greene, p. 194.

- ^ Tillery, pp. 111, 162.

- ^ Clayson, p. 306.

- ^ Greene, p. 198.

- ^ Greene, p. 133.

- ^ a b c Madinger & Easter, p. 439.

- ^ Leng, pp. 105, 133.

- ^ Woffinden, pp. 69–70.

- ^ George Harrison, pp. 246, 254, 258.

- ^ Tillery, pp. 111–12.

- ^ George Harrison, pp. 226, 248.

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 194–95.

- ^ "Chapter 1 – The Hare Krsna Mantra: 'There's nothing higher …' A 1982 Interview with George Harrison" Archived 24 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Chant and Be Happy/harekrishna.com (retrieved 9 April 2014).

- ^ Greene, pp. 194, 195.

- ^ Leng, p. 157.

- ^ Harrison, p. 246.

- ^ Anthony DeCurtis, "George Harrison All Things Must Pass", Rolling Stone, 12 October 2000 (retrieved 7 May 2013).

- ^ a b c Leng, p. 137.

- ^ Inglis, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Huntley, pp. 91–92.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 240.

- ^ a b Leng, p. 138.

- ^ a b Clayson, p. 322.

- ^ MacDonald, p. 326.

- ^ Graham Reid, "George Harrison Revisited, Part One (2014): The dark horse bolting out of the gate" Archived 17 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Elsewhere, 24 October 2014 (retrieved 4 December 2014).

- ^ Leng, pp. 126–28, 129–30, 131, 133.

- ^ a b Leng, p. 129.

- ^ Doggett, pp. 156, 157.

- ^ Leng, p. 131.

- ^ Tillery, p. 111.

- ^ Allison, pp. 141, 157.

- ^ Ingham, p. 134.

- ^ Inglis, pp. 39–40.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 385.

- ^ a b Schaffner, p. 160.

- ^ a b Madinger & Easter, p. 438.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 386.

- ^ Clayson, p. 315.

- ^ "Material World Charitable Foundation" > About Archived 22 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine, georgeharrison.com (retrieved 9 April 2014).

- ^ Huntley, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Schaffner, p. 142.

- ^ a b c Kevin Howlett, booklet accompanying Living in the Material World reissue (EMI Records, 2006; produced by Dhani & Olivia Harrison).

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 180.

- ^ a b c Badman, p. 83.

- ^ Timothy White, "George Harrison – Reconsidered", Musician, November 1987, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Spizer, p. 254.

- ^ a b Woffinden, p. 71.

- ^ Spizer, p. 255, 342.

- ^ Badman, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Schaffner, p. 159.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 155.

- ^ Clayson, p. 323.

- ^ a b c Leng, p. 125.

- ^ a b c Cavanagh, p. 43.

- ^ Lavezzoli, p. 200.

- ^ Woffinden, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Spizer, pp. 222, 254.

- ^ a b c d e f Bruce Eder, "George Harrison Living in the Material World" Archived 21 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, AllMusic (retrieved 10 April 2014).

- ^ a b Leng, p. 132.

- ^ MacDonald, p. 321.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 260.

- ^ a b Leng, p. 126.

- ^ Leng, p. 133.

- ^ a b Snow, p. 72.

- ^ George Harrison: Living in the Material World DVD, 2011 (directed by Martin Scorsese; produced by Olivia Harrison, Nigel Sinclair & Martin Scorsese).

- ^ Badman, p. 50.

- ^ Baron Wolman, Rocks Off: The Nicky Hopkins Website Archived 7 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine (retrieved 13 February 2012).

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 207.

- ^ Snow, p. 70.

- ^ Wyman, p. 415.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 112, 122.

- ^ Ken Hunt, "Review: Ravi Shankar Ali Akbar Khan, In Concert 1972", Gramophone, June 1997, p. 116.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 35.

- ^ Sounes, p. 272.

- ^ Badman, p. 89.

- ^ Badman, p. 84.

- ^ Leng, p. 127.

- ^ Woffinden, pp. 43, 70, 75.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 332–33.

- ^ Doggett, pp. 192–93.

- ^ Lavezzoli, p. 193.

- ^ Leng, p. 130.

- ^ a b Greene, p. 195.

- ^ Inglis, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Huntley, p. 92.

- ^ Schaffner, pp. 111, 159.

- ^ Leng, pp. 129, 134–35.

- ^ Badman, p. 91.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Spizer, p. 256.

- ^ Pierre Perrone, "Tom Wilkes: Graphic designer responsible for many celebrated album covers" Archived 10 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, 15 July 2009 (retrieved 31 March 2012).

- ^ Booklet accompanying Living in the Material World reissue (EMI Records, 2006; produced by Dhani & Olivia Harrison), p. 36.

- ^ Lavezzoli, p. 194.

- ^ Woffinden, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 324–25.

- ^ Tillery, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d Clayson, p. 324.

- ^ a b c Allison, p. 42.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 258.

- ^ a b c Madinger & Easter, p. 440.

- ^ Badman, pp. 94–95, 98.

- ^ a b Schaffner, p. 158.

- ^ Rodriguez, pp. 155, 258.

- ^ Spizer, p. 249.

- ^ George Harrison, plate XXXIII, p. 389.

- ^ Olivia Harrison, pp. 308–09.

- ^ Spizer, pp. 255–56.

- ^ Carr & Tyler, p. 106.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 125.

- ^ Doggett, p. 207.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 364.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 332, 364.

- ^ a b Badman, p. 103.

- ^ Leng, p. 128.

- ^ "Search: 07/07/1973" > Albums, Official Charts Company (retrieved 28 October 2013).

- ^ a b "Billboard Hits of the World", Billboard, 25 August 1973, p. 50 (retrieved 11 April 2014).

- ^ a b "RPM 100 Albums, June 30, 1973" Archived 6 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Library and Archives Canada (retrieved 9 April 2014).

- ^ a b "Certified for Canadian Gold" (CRIA trade advertisement) Archived 8 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, RPM, 11 January 1975, p. 6 (retrieved 12 May 2021).

- ^ "Capitol Canada", Billboard, 8 February 1975, p. 61 (retrieved 17 June 2021).

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 353–54, 364.

- ^ Badman, pp. 102, 104.

- ^ Harry, pp. 235, 291.

- ^ Leng, pp. 123, 140.

- ^ Huntley, pp. 94–95, 112.

- ^ Eliot Tiegel (ed.), "Top Album Picks: Pop", Billboard, 9 June 1973, p. 54 (retrieved 21 November 2014).

- ^ Melody Maker, 9 June 1973, pp. 1, 3.

- ^ a b Michael Watts, "The New Harrison Album", Melody Maker, 9 June 1973, p. 3.

- ^ a b The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 44.

- ^ a b Lavezzoli, p. 195.

- ^ Woffinden, p. 73.

- ^ a b Chris Hunt (ed.), NME Originals: Beatles – The Solo Years 1970–1980, IPC Ignite! (London, 2005), p. 70.

- ^ a b c Tony Tyler, "Holy Roller: Harrison", NME, 9 June 1973, p. 33.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (October 1973). "The Christgau Consumer Guide". Creem. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ a b Carr & Tyler, p. 107.

- ^ Michael Delaney & Anthony O'Grady, "Living in the Material World – George Harrison (Apple PAS 10006): A two-part appreciation", Ear for Music, September 1973, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Schaffner, pp. 159, 160.

- ^ a b Clayson, pp. 323–24.

- ^ Huntley, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Woffinden, pp. 69, 71–72.

- ^ Paul Du Noyer, "Back Catalogue: George Harrison", Blender, April 2004, pp. 152–53.

- ^ Hugh Fielder, "George Harrison Living In The Material World", Classic Rock, December 2006, p. 98.

- ^ a b Mat Snow, "George Harrison Living in the Material World", Mojo, November 2006, p. 124.

- ^ a b c John Metzger, "George Harrison Living in the Material World" Archived 26 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Music Box, vol. 13 (11), November 2006 (retrieved 10 April 2014).

- ^ Graff & Durchholz, p. 529.

- ^ Pricilia Decoene, "Critique de Living In The Material World, George Harrison" (in French), Music Story (archived version from 6 October 2015, retrieved 29 December 2016).

- ^ Gabriele Gambardella, "George Harrison: Il Mantra del Rock", OndaRock (retrieved 24 September 2021).

- ^ a b c d Zeth Lundy, "George Harrison: Living in the Material World" Archived 8 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, PopMatters, 8 November 2006 (retrieved 29 November 2014).

- ^ "George Harrison: Album Guide", rollingstone.com (archived version retrieved 5 August 2014).

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 157.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 188.

- ^ Dave Thompson, "The Music of George Harrison: An album-by-album guide", Goldmine, 25 January 2002, p. 17.

- ^ Tom Doyle, "George Harrison Living in the Material World", Q, November 2006, p. 156.

- ^ a b Shawn Perry, "George Harrison, Living in the Material World – CD Review" Archived 13 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Vintage Rock, October 2006 (retrieved 29 November 2014).

- ^ Cavanagh, p. 47.

- ^ Tyler Kane, "The 10 Best Beatles Solo Albums", Paste, 30 January 2012 (archived version retrieved 1 February 2021).

- ^ Michael Gallucci, "Paul McCartney: 'Egypt Station' Review" > "Ranking the Other Beatles Solo Albums" Archived 21 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Ultimate Classic Rock, 5 September 2018 (retrieved 1 February 2021).

- ^ Graeme Ross, "The Beatles: Their 10 best solo albums ranked, from Flaming Pie to Imagine" Archived 17 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, 16 April 2020 (retrieved 1 February 2021).

- ^ Chaz Lipp, "Music Review: George Harrison’s Apple Albums Remastered" Archived 7 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Blogcritics, 5 October 2014 (retrieved 6 October 2014).

- ^ Alex Franquelli, "George Harrison: The Apple Years 1968–75" Archived 8 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, PopMatters, 30 October 2014 (retrieved 1 November 2014).

- ^ Paul Trynka, "George Harrison: The Apple Years 1968–75" Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, TeamRock, 8 October 2014 (retrieved 27 November 2014).

- ^ Paul Trynka, "George Harrison The Apple Years 1968–75", Classic Rock, November 2014, p. 105.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 302, 323.

- ^ Rodriguez, pp. 156, 157.

- ^ Rip Rense, "The Rip Post Interview with Simon Leng", The Rip Post, 2006 (archived version retrieved 26 October 2013).

- ^ Leng, pp. 126, 129, 131–32, 141.

- ^ a b c d "Living in the Material World Re-Issue" Archived 20 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, georgeharrison.com, 22 June 2006 (retrieved 9 April 2014).

- ^ a b Jill Menze, "Billboard Bits: George Harrison, Family Values, Antony" Archived 26 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, billboard.com, 21 June 2006 (retrieved 26 November 2014).

- ^ "George Harrison Living in the Material World (Bonus Tracks/DVD)" > Track Listing – Disc 1 Archived 7 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, AllMusic (retrieved 9 April 2014).

- ^ Madinger & Easter, pp. 435, 442.

- ^ Booklet accompanying Living in the Material World reissue (EMI Records, 2006; produced by Dhani & Olivia Harrison), pp. 33, 36.

- ^ Kory Grow, "George Harrison's First Six Studio Albums to Get Lavish Reissues" Archived 23 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, rollingstone.com, 2 September 2014 (retrieved 1 October 2014).

- ^ a b Joe Marchese, "Give Me Love: George Harrison’s 'Apple Years' Are Collected on New Box Set" Archived 3 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Second Disc, 2 September 2014 (retrieved 1 October 2014).

- ^ David Fricke, "The Many Solo Moods of George Harrison: Inside 'The Apple Years' Box" Archived 28 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Rolling Stone, 26 September 2014 (retrieved 1 October 2014).

- ^ "Living in the Material World (50th Anniversary Deluxe Edition) [Box Set] by [George Harrison] Reviews and Tracks". Metacritic. Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ Emma Harrison, "George Harrison – Living In The Material World (50th Anniversary Edition)", Clash, 15 November 2024 (retrieved 16 November 2024).

- ^ a b Rob Sheffield, "George Harrison's "Living in the Material World" is a Slept-on Masterpiece Worth Rediscovering", Rolling Stone, 14 November 2024 (retrieved 16 November 2024).

- ^ Paolo Ragusa, "George Harrison's Living in the Material World to Receive 50th Anniversary Box Set Reissue", Consequence, 19 September 2024 (retrieved 21 September 2024).

- ^ Michael Bonner, "George Harrison's Living In The Material World due for super deluxe release", Uncut, 19 September 2024 (retrieved 21 September 2024).

- ^ Kenneth Womack, "George Harrison's "Living in the Material World" 50th anniversary deluxe remix sparkles", Salon.com, 15 November 2024 (retrieved 16 November 2024).

- ^ David Kent, Australian Chart Book 1970–1992, Australian Chart Book (St Ives, NSW, 1993; ISBN 978-0-646-11917-5).

- ^ a b "Billboard Hits of the World", Billboard, 11 August 1973, p. 65 (retrieved 9 April 2014).

- ^ "George Harrison – Living in the Material World" Archived 14 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine, dutchcharts.nl (retrieved 9 April 2014).

- ^ a b "InfoDisc: Tous les Albums classés par Artiste > Choisir un Artiste dans la Liste" Archived 9 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine (in French), infodisc.fr (retrieved 13 April 2014).

- ^ Oricon Album Chart Book: Complete Edition 1970–2005. Roppongi, Tokyo: Oricon Entertainment. 2006. ISBN 4-87131-077-9.

- ^ "George Harrison – Living in the Material World" Archived 27 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, norwegiancharts.com (retrieved 9 April 2014).

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "Swedish Charts 1972–1975/Kvällstoppen – Listresultaten vecka för vecka" > Juli 1973 > 17 & 24 Juli Archived 23 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine (in Swedish), hitsallertijden.nl (retrieved 13 February 2013).

- ^ "Artist: George Harrison" > Albums Archived 4 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Official Charts Company (retrieved 28 October 2013).

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 342.

- ^ Tony Lanzetta (dir.), "Billboard Top LP's & Tape" Archived 22 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Billboard, 14 July 1973, p. 64 (retrieved 21 February 2017).

- ^ "Cash Box Top 100 Albums", Cash Box, 14 July 1973, p. 37.

- ^ Lenny Beer (ed.), "The Album Chart", Record World, 14 July 1973, p. 28.

- ^ "Album – George Harrison, Living in the Material World" Archived 7 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, charts.de (retrieved 3 January 2013).

- ^ ジョージ・ハリスン-リリース-ORICON STYLE-ミュージック "Highest position and charting weeks of Living in the Material World (reissue) by George Harrison". oricon.co.jp (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) Oricon Style (retrieved 11 February 2012). - ^ "Billboard Albums", Billboard, 14 October 2006, p. 76 (retrieved 25 November 2014).

- ^ "Ultratop.be – George Harrison – Living in the Material World" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – George Harrison – Living in the Material World" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – George Harrison – Living in the Material World" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ "Oricon Top 50 Albums: 2024-11-25/p/5" (in Japanese). Oricon. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ David Kent, Australian Chart Book 1970–1992, Australian Chart Book (St Ives, NSW, 1993; ISBN 0-646-11917-6).

- ^ "Dutch charts jaaroverzichten 1973" (ASP) (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ "Les Albums (CD) de 1973 par InfoDisc" (in French). Archived from the original (PHP) on 27 October 2012. infodisc.fr (retrieved 13 April 2014).

- ^ "Billboard 1970's Album Top 50 (Part 1) > 1973" Archived 6 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 7 December 2007 (retrieved 13 April 2014).

- ^ "Top Pop Albums of 1973" Archived 4 December 2012 at archive.today, billboard.biz (retrieved 11 February 2012).

- ^ "From the Music Capitals of the World – Melbourne", Billboard, 17 November 1973, p. 56 (retrieved 17 February 2022).

- ^ "Artist: George Harrison / Title: Living in the Material World", RIAA Gold & Platinum Database (retrieved 12 May 2021).

Sources

[edit]- Dale C. Allison Jr., The Love There That's Sleeping: The Art and Spirituality of George Harrison, Continuum (New York, NY, 2006; ISBN 978-0-8264-1917-0).

- Keith Badman, The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001, Omnibus Press (London, 2001; ISBN 0-7119-8307-0).

- Roy Carr & Tony Tyler, The Beatles: An Illustrated Record, Trewin Copplestone Publishing (London, 1978; ISBN 0-450-04170-0).

- Harry Castleman & Walter J. Podrazik, All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975, Ballantine Books (New York, NY, 1976; ISBN 0-345-25680-8).

- David Cavanagh, "George Harrison: The Dark Horse", Uncut, August 2008, pp. 36–48.

- Alan Clayson, George Harrison, Sanctuary (London, 2003; ISBN 1-86074-489-3).

- Peter Doggett, You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the Breakup, It Books (New York, NY, 2011; ISBN 978-0-06-177418-8).

- The Editors of Rolling Stone, Harrison, Rolling Stone Press/Simon & Schuster (New York, NY, 2002; ISBN 0-7432-3581-9).

- Gary Graff & Daniel Durchholz (eds), MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide, Visible Ink Press (Farmington Hills, MI, 1999; ISBN 1-57859-061-2).

- Joshua M. Greene, Here Comes the Sun: The Spiritual and Musical Journey of George Harrison, John Wiley & Sons (Hoboken, NJ, 2006; ISBN 978-0-470-12780-3).

- George Harrison, I Me Mine, Chronicle Books (San Francisco, CA, 2002; ISBN 0-8118-3793-9).

- Olivia Harrison, George Harrison: Living in the Material World, Abrams (New York, NY, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4197-0220-4).

- Bill Harry, The George Harrison Encyclopedia, Virgin Books (London, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7535-0822-0).

- Elliot J. Huntley, Mystical One: George Harrison – After the Break-up of the Beatles, Guernica Editions (Toronto, ON, 2006; ISBN 1-55071-197-0).

- Chris Ingham, The Rough Guide to the Beatles (2nd edn), Rough Guides/Penguin (London, 2006; ISBN 978-1-84836-525-4).

- Ian Inglis, The Words and Music of George Harrison, Praeger (Santa Barbara, CA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-313-37532-3).

- Peter Lavezzoli, The Dawn of Indian Music in the West, Continuum (New York, NY, 2006; ISBN 0-8264-2819-3).

- Simon Leng, While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison, Hal Leonard (Milwaukee, WI, 2006; ISBN 1-4234-0609-5).

- Ian MacDonald, Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties, Pimlico (London, 1998; ISBN 0-7126-6697-4).

- Chip Madinger & Mark Easter, Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium, 44.1 Productions (Chesterfield, MO, 2000; ISBN 0-615-11724-4).

- Chris O'Dell with Katherine Ketcham, Miss O'Dell: My Hard Days and Long Nights with The Beatles, The Stones, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, and the Women They Loved, Touchstone (New York, NY, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4).

- Robert Rodriguez, Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles' Solo Years 1970–1980, Hal Leonard (Milwaukee, WI, 2010; ISBN 978-0-87930-968-8).

- Nicholas Schaffner, The Beatles Forever, McGraw-Hill (New York, NY, 1978; ISBN 0-07-055087-5).

- Mat Snow, "George Harrison: Quiet Storm", Mojo, November 2014, pp. 66–73.

- Howard Sounes, Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan, Doubleday (London, 2001; ISBN 0-385-60125-5).

- Bruce Spizer, The Beatles Solo on Apple Records, 498 Productions (New Orleans, LA, 2005; ISBN 0-9662649-5-9).

- Gary Tillery, Working Class Mystic: A Spiritual Biography of George Harrison, Quest Books (Wheaton, IL, 2011; ISBN 978-0-8356-0900-5).

- Bob Woffinden, The Beatles Apart, Proteus (London, 1981; ISBN 0-906071-89-5).

- Bill Wyman, Rolling with the Stones, Dorling Kindersley (London, 2002; ISBN 0-7513-4646-2).

External links

[edit]- Living in the Material World at Discogs (list of releases)

- Living in the Material World microsite (2006)