Long s

The long s, ⟨ſ⟩, also known as the medial s or initial s, is an archaic form of the lowercase letter ⟨s⟩, found mostly in works from the late 8th to early 19th centuries. It replaced one or both[a] of the letters s in a double-s sequence (e.g., "ſinfulneſs" for "sinfulness" and "poſſeſs" or "poſseſs" for "possess", but never "poſſeſſ").[1] The modern ⟨s⟩ letterform is known as the "short", "terminal", or "round" s. In typography, the long s is known as a type of swash letter, commonly referred to as a "swash s".[2] The long s is the basis of the first half of the grapheme of the German alphabet ligature letter ⟨ß⟩,[3] (eszett or scharfes s, 'sharp s'). As with other letters, the long s may have a variant appearance depending on typeface: ſ, ſ, ſ, ſ.

Rules

[edit]English

[edit]This list of rules for the long s is not exhaustive, and it applies only to books printed during the 17th to early 19th centuries in English-speaking countries.[1] Similar rules exist for other European languages.[1]

Long s was always used ("ſong", "ſubſtitute") except:

- Upper-case letters are always the round S; there is no upper-case long s.

- A round s was always used at the end of a word ending with ⟨s⟩: "his", "complains", "ſucceſs"

- However, long s was maintained in abbreviations such as "ſ." for "ſubſtantive" (substantive), and "Geneſ." for "Geneſis" (Genesis).

- Before an apostrophe (indicating an omitted letter), a round s was used: "us'd" and "clos'd".

- Before or after an f, a round s was used: "offset", "ſatisfaction".

- In the 17th and early 18th centuries, the round s was used before k and b: "ask", "husband", Ailesbury, Salisbury, Shaftsbury;[4] in the late 18th century: "aſk", "huſband", "Aileſbury", "Saliſbury" "Shaftſbury".

- These two exceptions applied only if the letters were physically adjacent on the page, and long s was used if the two were separated by a hyphen and line break, e.g. "off-ſet", "Saliſ-bury".

- There were no special exceptions for a double s. The first s was always long, while the second was long in mid-word (e.g. "poſſeſſion"), or short when at the end of a word (e.g. "poſſeſs"). See, for example, the word "Bleſſings" in the Preamble to the United States Constitution.

- Round s was used at the end of each word in a hyphenated compound word: "croſs-piece".

- In the case of a triple s, such words were normally hyphenated with a round s, e.g. "croſs-ſtitch", but a round s was used even if the hyphen was omitted: "croſsſtitch".

In handwriting, these rules did not apply—the long s was usually confined to preceding a round s, either in the middle or at the end of a word—for example, "aſsure", "bleſsings".[1]

German

[edit]The general idea is that round s indicates the end of a semantic part. Thus, long ſ is used everywhere except at the end of a syllable, where further conditions need to be true.

The following rules were laid down at the German Orthographic Conference of 1901.

The round s is used:

- at the end of (non-abbreviated) words:

e.g. das Haus, der Kosmos, des Bundes, das Pils

(however: im Hauſe, die Häuſer, das Pilſener)

- at the end of prefixes, as a connecting s and in compounds at the end of the first part-word, even if the following part-word begins with a long ſ:

e.g. Liebesbrief, Arbeitsamt, Donnerstag, Unterſuchungsergebnis, Haustür, Dispoſition, disharmoniſch, dasſelbe, Wirtsſtube, Ausſicht

- in derivations with word formation suffixes that begin with a consonant, such as -lein, -chen, -bar, etc. (not before inflectional endings with t and possibly schwa [ə]):

e.g. Wachstum, Weisheit, Häuslein, Mäuschen, Bistum, nachweisbar, wohlweislich, boshaft

(however: er reiſte, das ſechſte, cf. below ſt)

- at the end of a syllable, even if the syllable is not the end of a (part-)word, common in names and proper nouns:

e.g. kosmiſch, brüskieren, Realismus, lesbiſch, Mesner; Oswald, Dresden, Schleswig, Osnabrück

Many exceptions apply.

Long ſ is used whenever round s is not used (for s):

- at the beginning of a syllable, i.e. anywhere before the vowel in the center of a syllable:

e.g. ſauſen, einſpielen, ausſpielen, erſtaunen, ſkandalös, Pſyche, Miſanthrop (syllables: Mi⋅ſan⋅throp)

The same applies for the beginning of a syllable of a suffix like -ſel, -ſal, -ſam, etc.:

e.g. Rätſel, Labſal, ſeltſam

- in ſp and ſt (since 1901 also ſz), unless they arise by happenstance (via a connecting s or composition); that includes flexion suffixes starting with t:

e.g. Weſpe, Knoſpe, faſten, faſzinierend, Oſzillograph, Aſt, Haſt, Luſt, einſt, du ſtehſt, meiſtens, beſte, knuſpern; er reiſt, du lieſt, es paſſte (modern orthography; traditionally: paßte), ſechſte, Gſtaad

- in multigraphs that represent a single sound such as ſch (to represent /ʃ/, but not /sx/) and English ſh and doubled consonants ſſ and ſs:

e.g. Buſch, Eſche, Wunſch, wünſchen, Flaſh, Waſſer, Biſſen, Zeugniſſe, Faſs (modern orthography.; traditionally: Faß), however: Eschatologie

Also applies to double s through assimilation:

e.g. aſſimiliert, Aſſonanz

- before l, n, and r if an e is omitted:

e.g. unſre, Pilſner, Wechſler

however: Zuchthäusler, Oslo, Osnabrück

- before an apostrophe and other forms of abbreviation:

e.g. ich laſſ’ es (casual for ich laſſe es), ſ. (common abbreviation for ſiehe)

- when the initial ſ of a word is merged with and has priority over the terminal s of a prefix:

e.g. in tranſzendent, tranſzendieren, etc.; in this case, the initial ſ of ſzend is merged with the terminal s of the trans prefix due to z following the ſ.

These rules do not cover all cases and in some corner cases, multiple variants can be found. One such case is whether to apply original semantics (that are largely unknown) or follow spoken syllables; e.g. in Asbest vs. Aſbest as it is spoken As⋅best, but comes from Ancient Greek ἄσβεστος composed of ᾰ̓- plus σβέννῡμῐ, meaning a is a prefix, and thus, a long ſ follows.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2019) |

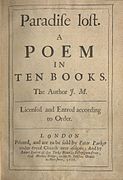

The long s was derived from the old Roman cursive medial s, ⟨![]() ⟩.[5] When the distinction between majuscule (uppercase) and minuscule (lowercase) letter forms became established, toward the end of the eighth century, it developed a more vertical form.[6] During this period, it was occasionally used at the end of a word, a practice that quickly died but that was occasionally revived in Italian printing between about 1465 and 1480. Thus, the general rule that the long s never occurred at the end of a word is not strictly correct, although the exceptions are rare and archaic. The double s in the middle of a word was also written with a long s and a short s, as in: "Miſsiſsippi".[7] In German typography, the rules are more complicated: short s also appears at the end of each component within a compound word, and there are more detailed rules and practices for special cases.

⟩.[5] When the distinction between majuscule (uppercase) and minuscule (lowercase) letter forms became established, toward the end of the eighth century, it developed a more vertical form.[6] During this period, it was occasionally used at the end of a word, a practice that quickly died but that was occasionally revived in Italian printing between about 1465 and 1480. Thus, the general rule that the long s never occurred at the end of a word is not strictly correct, although the exceptions are rare and archaic. The double s in the middle of a word was also written with a long s and a short s, as in: "Miſsiſsippi".[7] In German typography, the rules are more complicated: short s also appears at the end of each component within a compound word, and there are more detailed rules and practices for special cases.

Similarity to letter f

[edit]

The long s is often confused with the minuscule ⟨f⟩, sometimes even having an f-like nub at its middle but on the left side only in various roman typefaces and in blackletter. There was no nub in its italic type form, which gave the stroke a descender that curled to the left and which is not possible without kerning in the other type forms mentioned. For this reason, the short s was also normally used in combination with f: for example, in "ſatisfaction".[citation needed]

The nub acquired its form in the blackletter style of writing. What looks like one stroke was actually a wedge pointing downward. The wedge's widest part was at that height (x-height) and capped by a second stroke that formed an ascender that curled to the right. Those styles of writing, and their derivatives, in type design had a crossbar at the height of the nub for letters f and t, as well as for k. In roman type, except for the crossbar on medial s, all other cross bars disappeared.[citation needed]

Ligatures

[edit]

The long s was used in ligatures in various languages. Four examples were ⟨si⟩, ⟨ss⟩, ⟨st⟩, and the German letter Eszett ⟨ß⟩.[citation needed]

The present-day German letter ß (German: Eszett or scharfes s; also used in Low German and historical Upper Sorbian orthographies) is generally considered to have originated in a (Fraktur) ligature of ⟨ſz⟩ (which is supported by the fact that the second part of the ⟨ß⟩ grapheme usually resembles a Fraktur z: ⟨⟩, hence ⟨ſ⟩), although in Antiqua, the ligature of ⟨ſs⟩ is used instead. An alternative hypothesis claims that the German letter ß originated in Tironian notes.[8]

ſ and s as distinct letters

[edit]Some old orthographic systems of Slavonic and Baltic languages used ⟨ſ⟩ and ⟨s⟩ as two separate letters with different phonetic values. For example, the Bohorič alphabet of the Slovene language included ⟨ſ⟩ /s/, ⟨s⟩ /z/, ⟨ſh⟩ /ʃ/, ⟨sh⟩ /ʒ/. In the original version of the alphabet, majuscule ⟨S⟩ was shared by both letters.[citation needed]

Decline

[edit]

In general, the long s fell out of use in roman and italic typefaces in professional printing well before the middle of the 19th century. It rarely appears in good-quality London printing after 1800, though it lingers provincially until 1824 and is found in handwriting into the second half of the nineteenth century,[10] and is sometimes seen later on in archaic or traditionalist printing such as printed collections of sermons. Woodhouse's The Principles of Analytical Calculation, published by the Cambridge University Press in 1803, uses the long s throughout its roman text.[11]

Abandonment by printers and type founders

[edit]

The long s disappeared from new typefaces rapidly in the mid-1790s, and most printers who could afford to do so had discarded older typefaces by the early years of the 19th century. Pioneer of type design John Bell (1746–1831), who started the British Letter Foundry in 1788, is often "credited with the demise of the long s".[12] Paul W. Nash concluded that the change mostly happened very fast in 1800, and believes that this was triggered by the Seditious Societies Act. To discourage subversive publications, this required printing to name the identity of the printer, and so in Nash's view gave printers an incentive to make their work look more modern.[13]

Unlike the 1755 edition, which uses the long s throughout,[14] the 1808 edition of the Printer's Grammar describes the transition away from the use of the long s among type founders and printers in its list of available sorts:

The introduction of the round s, instead of the long, is an improvement in the art of printing equal, if not superior, to any which has taken place in recent years, and for which we are indebted to the ingenious Mr. Bell, who introduced them in his edition of the British Classics [published in the 1780s and 1790s]. They are now generally adopted, and the [type founders] scarcely ever cast a long s to their fonts, unless particularly ordered. Indeed, they omit it altogether in their specimens ... They are placed in our list of sorts, not to recommend them, but because we may not be subject to blame from those of the old school, who are tenacious of deviating from custom, however antiquated, for giving a list which they might term imperfect.

— Caleb Stower, The Printer's Grammar (1808).[15]

An individual instance of an important work using s instead of the long s occurred in 1749, with Joseph Ames's Typographical Antiquities, about printing in England 1471–1600, but "the general abolition of long s began with John Bell's British Theatre (1791)".[10][b]

In Spain, the change was mainly accomplished between the years 1760 and 1766;[13] for example, the multivolume España Sagrada made the switch with volume 16 (1762). In France, the change occurred between 1782 and 1793: François Didot designed Didone to be used substantially without long s.[13] The change happened in Italy at about the same time: Giambattista Bodoni also designed his Bodoni typeface without long s.[13] Printers in the United States stopped using the long s between 1795 and 1810: for example, acts of Congress were published with the long s throughout 1803, switching to the short s in 1804. In the US, a late use of the long s was in Low's Encyclopaedia, which was published between 1805 and 1811. Its reprint in 1816 was one of the last such uses recorded in the US. The most recent recorded use of the long s typeset among English printed Bibles can be found in the Lunenburg, Massachusetts, 1826 printing by W. Greenough and Son. The same typeset was used for the 1826 printed later by W. Greenough and Son, and the statutes of the United Kingdom's colony Nova Scotia also used the long s as late as 1816. Some examples of the use of the long and short s among specific well-known typefaces and publications in the UK include the following:

- The Caslon typeface of 1732 has the long s.[16]

- The Caslon typeface of 1796 has the short s only.[16]

- In the UK, The Times of London made the switch from the long to the short s with its issue of 10 September 1803.

- The Catherwood typeface of 1810 has the short s only.[16]

- Encyclopædia Britannica's 5th edition, completed in 1817, was the last edition to use the long s.[17] The 1823 6th edition uses the short s.

- The Caslon typeface of 1841 has the short s only.[16]

- Two typefaces from Stephenson Blake, both 1838–1841, have the short s only.[16]

When the War of 1812 began, the contrast between the non-use of the long s by the United States, and its continued use by the United Kingdom, is illustrated by the Twelfth US Congress's use of the short s of today in the US declaration of war against the United Kingdom, and, in contrast, the continued use of long s within the text of Isaac Brock's counterpart document responding to the declaration of war by the US.[citation needed]

Early editions of Scottish poet Robert Burns that have lost their title page can be dated by their use of the long s; that is, James Currie's edition of the Works of Robert Burns (Liverpool, 1800 and many reprintings) does not use the long s, while editions from the 1780s and early 1790s do.[citation needed]

In printing, instances of the long s continue in rare and sometimes notable cases in the UK until the end of the 19th century, possibly as part of a consciously antiquarian revival of old-fashioned type. For example:

- The Chiswick Press reprinted the Wyclyffite New Testament in 1848 in the Caslon typeface,[18] using the long s; Chiswick Press, run by Charles Whittingham II (nephew of Charles Whittingham) from c. 1832–1870s, reprinted classics like Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales in a typeface of Caslon that included the long s.

- The "antiqued" first edition of Thackeray's The History of Henry Esmond (1852), a historical novel set in the eighteenth century, prints long s, and not just when doubled as in "mistreſs's".[19][20][21]

- Mary Elizabeth Coleridge's first volume of poetry, Fancy's Following, published in 1896, was printed with the long s.[22]

- Collections of sermons were published using the long s until the end of the 19th century.[citation needed]

In Germany, Fraktur-family typefaces (such as Tannenberg, used by Deutsche Reichsbahn for station signage, as illustrated above) continued in widespread official use until the "Normal Type" decree of 1941 required that they be phased out. (Private use had already largely ceased.) The long s survives in Fraktur typefaces.

Eventual abandonment in handwriting

[edit]

After its decline and disappearance in printing in the early years of the 19th century, the long s persisted into the second half of the century in manuscript. In handwriting used for correspondence and diaries, its use for a single s seems to have disappeared first: most manuscript examples from the 19th century use it for the first s in a double s. For example,

- Charlotte Brontë used the long s, as the first in a double s, in some of her letters, e.g., "Miſs Austen" in a letter to the critic G. H. Lewes, 12 January 1848; in other letters, however, she uses the short s, for example in an 1849 letter to Patrick Brontë, her father.[23] Her husband Arthur Bell Nicholls used the long s in writing to Ellen Nussey of Brontë's death.[24]

- Edward Lear regularly used the long s in his diaries in the second half of the 19th century; for example, his 1884 diary has an instance in which the first s in a double s is long: "Addreſsed".[25]

- Wilkie Collins routinely used the long s for the first in a double s in his manuscript correspondence; for example, he used the long s in the words "mſs" (manuscripts) and "needleſs" in a 1 June 1886 letter to Daniel S. Ford.[26]

For these as well as others, the handwritten long s may have suggested type and a certain formality as well as the traditional. Margaret Mathewson "published" her Sketch of 8 Months a Patient in the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, A.D. 1877 of her experiences as a patient of Joseph Lister in the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh by writing copies out in manuscript.[c] In place of the first s in a double s, Mathewson recreated the long s in these copies, a practice widely used for both personal and business correspondence by her family, who lived on the remote island of Yell, Shetland. The practice of using the long s in handwriting on Yell, as elsewhere, may have been a carryover from 18th-century printing conventions, but it was not unfamiliar as a convention in handwriting.[citation needed]

Modern usage

[edit]

The long s survives in elongated form, with an italic-styled curled descender, as the integral symbol ∫ used in calculus. Gottfried Leibniz based the character on the Latin summa ('sum'), which he wrote ſumma. This use first appeared publicly in his paper De Geometria, published in Acta Eruditorum of June 1686,[27] but he had been using it in private manuscripts at least since 29 October 1675.[28] The integral of a function f(x) with respect to a real variable x over the interval [a, b] is typeset as:[citation needed]

In linguistics, a similar character (ʃ, called esh) is used in the International Phonetic Alphabet, in which it represents the voiceless postalveolar fricative, the first sound in the English word ship.[citation needed]

In Nordic and German-speaking countries, relics of the long s continue to be seen in signs and logos that use various forms of fraktur typefaces. Examples include the logos of the Norwegian newspapers Aftenpoſten and Adresſeaviſen; the packaging logo for Finnish Siſu pastilles; and the German Jägermeiſter logo.[citation needed]

The long s exists in some current OpenType digital fonts that are historic revivals, like Caslon, Garamond, and Bodoni.[29]

Some Latin alphabets devised in the 1920s for some Caucasian languages used the ⟨ſ⟩ for some specific sounds.[30] These orthographies were in actual use until 1938.[31] Some of these developed a capital form which resembles the IPA letter ⟨ʕ⟩ .[citation needed]

In the 1993 Turkmen orthography, ⟨ſ⟩ represented /ʒ/; however, it was replaced by 1999 by the letter ⟨ž⟩. The capital form was ⟨£⟩, which was replaced by ⟨Ž⟩.[32][33]

In Unicode

[edit]- U+017F ſ LATIN SMALL LETTER LONG S

- A long s with a bar diacritic, ⟨ẜ⟩ is encoded as U+1E9C ẜ LATIN SMALL LETTER LONG S WITH DIAGONAL STROKE

Solidus or slash

[edit]An echo of the long s survives today in the form of the mark /, popularly known as a "slash" but formally named a solidus. The mark is an evolution of the long s which was used as the abbreviation for 'shilling' in Britain's pre-decimal currency, originally written as in 7ſ 6d, later as "7/6", meaning "seven shillings and six pence".[34]

Gallery

[edit]-

Long s with capital and lowercase as used in Reform, journal of the Allgemeiner Verein für vereinfachte Rechtschreibung, in the 1890s

-

Unusual capital form of long s in Ehmcke-Antiqua typeface

-

Wayside cross near Hohenfurch, Germany, erected 1953, showing the long s in a roman typeface

-

Detail of a memorial in Munich, Germany, showing the text Wasser-Aufsehers-Gattin ('water attendant's wife') containing a long s adjacent to an f

See also

[edit]- ß (Eszett) – Letter of the Latin alphabet; used in German

- Insular S – Insular form of the letter S (Ꞅ)

- Esh (letter) – Character and IPA symbol (Ʃ, ʃ)

- Integral Symbol (∫) – Mathematical symbol used to denote integrals and antiderivatives

- R rotunda – Variant of the Latin letter R (ꝛ)

- Long I – Letter variant

- Sigma – Eighteenth letter of the Greek alphabet (Σ) similarly has two lowercase forms, ς in word-final position and σ otherwise

- Cool S - stylized children’s doodle of the letter S

Notes

[edit]- ^ Depending on whether they appear in the end or middle of a word, respectively. Some texts starting from the late 18th century had it exclusively replace the first s, however. A more detailed explanation follows below.

- ^ For fuller information, Attar cites: Nash, Paul W. (2001). "The Abandoning of the Long 's' in Britain in 1800". Journal of the Printing Historical Society (3): 3–19.

- ^ The still-unpublished manuscript of this Sketch is held by the Shetland Museum and Archives.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d West, Andrew (June 2006). "The Rules for Long S". Babelstone (blog). Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Berger, Sidney (2016). The Dictionary of the Book: A Glossary for Book Collectors, Booksellers, Librarians, and Others. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 252, 295. ISBN 9781442263390.

- ^ Cheng, Karen (2006). Designing Type. Laurence King Publishing. p. 212. ISBN 9781856694452.

- ^ Anthony Ashley Cooper Earl of Shaftesbury (1705). The Earl of Shaftsbury's Case Upon the Habeas Corpus Act. printed, for G. Sawbridge.

- ^ Yule, John-David. Concise Encyclopedia of Science and Technology. Crescent Books (1978) ISBN 9780517486108 p. 490

- ^ Davies, Lyn (2006), A is for Ox, London: Folio Society.

- ^ Lowe's 1800 map of the USA

- ^ Bollwage, Max (1999). "Ist das Eszett ein lateinischer Gastarbeiter?". Gutenberg-Jahrbuch [Gutenberg Yearbook] (in German). Gutenberg-Gesellschaft. pp. 35–41. ISBN 978-3-7755-1999-1. Cited and discussed in: Stötzner, Uta (2006). "Die Geschichte des versalen Eszetts". Signa (in German). 9. Grimma: 21–22. ISBN 978-3-933629-17-3.

- ^ Kapidakis, Sarantos; Mazurek, Cezary; Werla, Marcin (2015). Research and Advanced Technology for Digital Libraries. Springer. pp. 257–260. ISBN 9783319245928. Archived from the original on 20 July 2023. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ a b Attar, Karen (2010). "S and Long S". In Michael Felix Suarez; H. R. Woudhuysen (eds.). Oxford Companion to the Book. Vol. II. p. 1116. ISBN 9780198606536..

- ^ Woodhouse, Robert (1 January 1803). The principles of analytical calculation. Printed at the University press.

- ^ Bell, John (2010). Michael Felix Suarez; H. R. Woudhuysen (eds.). Oxford Companion to the Book. Vol. I. p. 516. ISBN 9780198606536.

- ^ a b c d Nash, Paul W. (2001). "The abandoning of the long s in Britain in 1800". Journal of the Printing Historical Society. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023. Noted in Morgan, Paul (2002). "The Use of the Long 's' in Britain: a Note". Quadrat (15): 23–28. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ Smith, John (1755). The printer's grammar: containing a concise history of the origin of printing;. London.

- ^ Stower, Caleb (1808). The Printer's Grammar; Or Introduction to the Art of Printing: Containing a Concise History of the Art, with the Improvements in the Practice of Printing, for the Last Fifty Years. p. 53. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Philip Gaskell, New Introduction to Bibliography, Clarendon, 1972, p. 210, Figs 74, 75.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica (5th ed.). 1817..

- ^ Wells, John Edwin (1970). A Manual of the Writings in Middle English 1050–1500. Modern Language Association of America. p. 548..

- ^ Daniel Hack (2005). The Material Interests of the Victorian Novel. Victorian Literature and Culture series. University of Virginia Press. p. 12. Figure 1 prints a facsimile of a sample page.

- ^ J. A. Sutherland (2013). "Henry Esmond: The Virtues of Carelessness". Thackeray at Work (reprint). Bloomsbury Academic Collections: English Literary Criticism: 18th–19th Centuries. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic: 56–73. doi:10.5040/9781472554260.ch-003.

- ^ Mosley, James. "Recasting Caslon Old Face". Type Foundry. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ Coleridge, Mary (1896). Fancy's Following. Oxford: Daniel Press.

- ^ Smith, Margaret, ed. (2000). The Letters of Charlotte Brontë: With a Selection of Letters by Family and Friends. Vol. Two (1848–1851). Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 406 and 407..

- ^ Smith, Margaret, ed. (2004). The Letters of Charlotte Brontë: With a Selection of Letters by Family and Friends. Vol. Three (1852–1855). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. opposite 217..

- ^ Edward Lear. Edward Lear Diaries, 1858–1888. Houghton Library, Harvard: MS Eng 797.3 (27). Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ Collins, Wilkie. "To Daniel S. Ford". In Paul Lewis (ed.). The Wilkie Collins Pages: Wilkie's Letters. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Swetz, Frank J. "Mathematical Treasure: Leibniz's Papers on Calculus – Integral Calculus". Convergence. Mathematical Association of America. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ Leibniz, G. W. (2008) [29 October 1675]. "Analyseos tetragonisticae pars secunda". Sämtliche Schriften und Briefe, Reihe VII: Mathematische Schriften (PDF). Vol. 5: Infinitesimalmathematik 1674–1676. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. pp. 288–295. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ Strizver, Ilene (2014). Type Rules!: The Designer's Guide to Professional Typography (4th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-118-45405-3.

- ^ Proposal to encode Latin letters used in the Former Soviet Union (in Unicode) (PDF), DK UUG, archived (PDF) from the original on 23 May 2012, retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ Frings, Andreas (2007). Sowjetische Schriftpolitik zwischen 1917 und 1941 – eine handlungstheoretische Analyse [Soviet scripts politics between 1917 and 1941 – an action-theoretical analysis] (in German). F. Steiner. ISBN 978-3-515-08887-9..

- ^ Ercilasun, Ahmet B. (1999). "The Acceptance of the Latin Alphabet in the Turkish World" (PDF). Studia Orientalia Electronica. 87: 63–70. ISSN 2323-5209. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2023. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ "Roman Alphabet of Turkmen". Institute of the Estonian Language. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ Fowler, Francis George (1917). "solidus". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English. p. 829 – via archive.org.

sǒ·lidus, n. (pl. -di). (Hist.) gold coin introduced by Roman Emperor Constantine; (only in abbr. s.) shilling(s), as 7s. 6d., £1 1s.; the shilling line (for ſ or long s) as in 7/6. [LL use of L SOLIDus]

(The name shilling is derived from a Roman coin, the solidus.)

External links

[edit]- Moore. "A Simple Explanation of the Correct Usage of Long and Short S". Alice – via Imgur.

- Mosley, James (January 2008). "Long s". Type Foundry – via Blogspot.

- "Why did 18th-century writers use F inftead of S?". "Classics" department. The Straight Dope. 6 November 1981. Archived from the original on 4 September 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2003.

- West, Andrew (June 2006). "The Long and the Short of the Letter S". Babelstone.

- "The American Declaration of Independence with long s". Unknown.nu.