Rid of Me

| Rid of Me | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 26 April 1993[1] | |||

| Recorded | December 1992 | |||

| Studio | Pachyderm, Cannon Falls, USA | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 48:02 | |||

| Label | Island | |||

| Producer | Steve Albini | |||

| PJ Harvey chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Rid of Me | ||||

| ||||

Rid of Me is the second studio album by the English singer-songwriter PJ Harvey, released on 26 April 1993 by Island Records, approximately one year after the release of her critically acclaimed debut studio album Dry (1992). It marked a departure from Harvey's previous songwriting, being more raw and aggressive than its predecessor.

The songs on Rid of Me were performed by Harvey's eponymous trio, consisting of Harvey on guitar and vocals, Rob Ellis on drums and backing vocals, and Steve Vaughan on bass guitar. Most of the songs on the album were recorded by Steve Albini, and it was the last album they recorded as a trio before disbanding in late 1993. Rid of Me was met with critical acclaim, and is widely regarded as one of the greatest albums of the 1990s and of all time, ranking at number 153 on the 2020 version of Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time (up from 406 on the list's previous edition).

Background and history

[edit]Harvey's first two studio albums were recorded in quick succession and their histories intertwine. In October 1991, she released her debut single "Dress". She signed a recording contract with indie record label Too Pure and relocated to London with her bandmates. Almost immediately after the single's release, she began to receive serious positive attention from music critics in both the UK and United States. This led to several major record labels vying to sign her. Harvey was initially reluctant to sign to a major label fearing she might lose artistic control of her music, but eventually decided to sign with Island Records in February 1992. A month later, Too Pure released her debut studio album Dry, containing both "Dress" and "Sheela-Na-Gig", her second single. Island would later distribute Dry under its Indigo imprint.

The band toured extensively in the UK and US to support Dry. Harvey turned down an offer to play the Lollapalooza festival in the summer of 1992,[7] but did play the Reading Festival that August. By this time, non-stop touring had begun to take its toll on Harvey's health. She suffered from what has been described as a nervous breakdown, brought on by a number of factors including exhaustion,[8] poor eating habits, and the break-up of a relationship.[9][10] Making matters worse, Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design, where she had been accepted for study, refused to hold her place for her any longer.[11] She left her London apartment and retreated to her native Dorset. While recuperating in October 1992, she worked on the songs that would appear on Rid of Me.

Music and lyrics

[edit]Structurally, Harvey continued to complicate her songwriting by utilising "strangely skewed time signatures and twisty song structures",[13] resulting in songs that "tilt toward performance art".[14]

The album's lyrics have been widely interpreted as being feminist in nature. Harvey, however, repeatedly denied a feminist agenda in her songwriting, stating "I don’t even think of myself as being female half the time. When I'm writing songs I never write with gender in mind. I write about people's relationships to each other. I'm fascinated with things that might be considered repulsive or embarrassing. I like feeling unsettled, unsure."[13] Some of the lyrics were inspired by her personal experiences. The title track, for instance, was admittedly influenced by one of Harvey's relationships coming to an end. When told by an interviewer that "Rid of Me" sounded psychotic, she replied that she wrote the song "at my illest" and added "I was almost psychotic" at the time.[9] But, she made it clear that not all of the lyrics were to be read autobiographically, saying "I would have to be 40 and very worn out to have lived through everything I write about".[9]

The album also includes a cover version of Bob Dylan's 1965 song "Highway 61 Revisited". Harvey's mother and father, both Dylan fans, had suggested that she record the track.[15]

Recording

[edit]In the late fall of 1992 the trio embarked on a short US tour. When the tour concluded in December they stayed in America to record their new album at the secluded Pachyderm Recording Studios in Cannon Falls, Minnesota. Harvey chose Chicago musician and sound engineer Steve Albini to record the album.[16] Harvey had admired Albini's distinctively raw recordings of bands like Pixies, Slint, the Breeders and the Jesus Lizard.

The recording session took place over a two-week period, but according to Harvey the bulk of the recording was done in three days.[17] Most of the songs were played live in the studio. Harvey spoke highly of Albini's recording, stating, "He's the only person I know that can record a drum kit and it sounds like you're standing in front of a drum kit. It doesn't sound like it's gone through a recording process or it's coming out of speakers. You can feel the sound he records, and that is why I wanted to work with him, 'cause all I ever wanted is for us to be recorded and to sound like we do when we're playing together in a room".[17]

She also gave insight into his recording methods, saying "The way that some people think of producing is to sort of help you to arrange or contributing or playing instruments, he does none of that. He just sets up his microphones in a completely different way from which I've ever seen anyone set up mics before, and that was astonishing. He'd have them on the floor, on the walls, on the windows, on the ceiling, twenty feet away from where you were sitting... He's very good at getting the right atmosphere to get the best take."[18]

The song "Man Size Sextet" was not recorded by Albini. It was instead produced by Harvey, Rob Ellis, and Head.

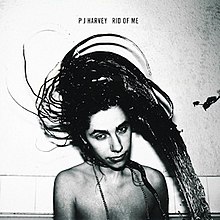

Artwork

[edit]The cover of the album depicts Harvey topless and swinging her drenched hair into the air. The photo was captured by Harvey's friend and photographer Maria Mochnacz, and was taken in Mochnacz's bathroom in her flat in Bristol. Due to the small size of the room, she had to place her camera against the wall opposite Harvey and could not look through the camera's viewfinder. The photo was taken in total darkness and only illuminated by the split-second flash.

When the photo was delivered to Island Records, Mochnacz was told that the imperfections in the picture (such as the water drops on the wall and the house plant) could be removed. She protested this decision, responding, "It's supposed to be like that – It's part of the picture".[19]

Release and critical reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Entertainment Weekly | D[21] |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| Mojo | |

| NME | 8/10[24] |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[25] |

| Record Collector | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| The Village Voice | A[29] |

Rid of Me was released in the United Kingdom on 26 April 1993,[1] and was met with widespread critical acclaim. Melody Maker raved that "No other British artist is so aggressively exploring the dark side of human nature, or its illogical black humour; no other British artist possesses the nerve, let alone the talent, to conjure up its soundtrack."[30] Veteran UK disc jockey (DJ) and radio presenter John Peel, a supporter of Harvey since the beginning of her career, added "You're initially so taken aback by what you're hearing. But you go back again and again and it implants itself on your consciousness."[31] The San Francisco Chronicle called Harvey "A talent and a singular voice that demands to be heard."[32] Evelyn McDonnell of Spin wrote that Harvey made it a point to "confound expectations and stereotypes".[33] The album also drew attention from more established musicians. Elvis Costello, for example, commented that a lot of Harvey's songs "seem to be about blood and fucking", a statement Harvey disagreed with.[34]

"I was surprised at people's positive reaction to Rid of Me. I liked it but I thought it was a very...difficult album. I thought people who had the first album wouldn't like it."

–PJ Harvey[9]

Steve Albini's production of the record proved controversial. Critics were divided over whether his recording complemented Harvey's voice or buried it. On the positive side, it was written that "Albini deftly balances heavy feedback and distortion with unexpected quiet breaks, making this release more musically diverse – and ultimately more satisfying – than PJ Harvey's debut."[35] But others considered the recording too harsh, saying "Steve Albini's deliberately crude production leaves everything minimal and rough, as if the whole album were recorded in somebody's basement, with the drums set up in a bathroom to clatter as chaotically as possible."[36] Another review called it simply "a trial to endure".[37] Critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine tried to reconcile Albini's production with Harvey's songs. He admitted the album has a "bloodless, abrasive edge" that leaves "absolutely no subtleties in the music", but theorises that Albini's recordings "may be the aural embodiment of the tortured lyrics, and therefore a supremely effective piece of performance art, but it also makes Rid of Me a difficult record to meet halfway."[20]

Harvey herself was pleased with the result. "I do everything for myself primarily," she said, "and I was happy with it. I don't really listen when people say good things about my work because I tend to not give myself praise about anything. But I was really pleased with Rid of Me. For that period of my life, it was perfect. Well, it wasn't perfect but as near to as I could get at that time".[11] She remained friends with Albini afterward, finding in him a kindred spirit. "People read things in and make him what they want him to be," Harvey said. "He's the only other person I know that that happens to besides myself. People have a very specific idea of what I am – some kind of ax-wielding, man-eating Vampira – and I'm not that at all. I'm almost the complete opposite."[38]

The album yielded two singles: "50ft Queenie" and "Man-Size". The music videos for both songs were directed by Maria Mochnacz. "50ft Queenie" was named a buzzworthy video by MTV in the Spring of 1993.

Legacy and impact

[edit]Rid of Me is regarded as an iconic album within alternative music. In 2016, Zach Schonfeld of Stereogum dubbed it not just one of the alternative era's "greatest [and] scariest rock albums," but that "of any era."[39] In 2022, it was included on an Alternative Press list titled "20 albums that paved the way for alternative as we know it".[40] The following year, Louder Sound's Emma Johnston saw that, in Rid's wake, the genre's "host of uncompromised confessionals" drew inspiration from it.[41]

Rid has impacted and garnered admiration from various musicians in the years since its release. In 2005, Spin's Caryn Ganz saw that the way for the band Elastica and musician Karen O was paved by the album's "poetically demented blues".[42] In 2009, BBC Music's Mike Diver wrote of its part in ushering its era's wave of "angst-ridden" women songwriters in. He saw Jagged Little Pill, the 1995 album by singer Alanis Morissette, bear the imprint of Harvey's "bare-all performances" on Rid.[43] Albumism's Liz Itkowsky called Harvey's guitar work on "Missed" "almost emo" and felt that it anticipated Midwest emo band American Football.[44] Emma Johnston called the album "a touchstone" for modern musicians like Phoebe Bridgers and Ethel Cain.[41]

Some of Harvey's peers have expressed their admiration for the album. Reflecting on her band Hole's second studio album Live Through This (1994) in a 2014 Spin interview, musician Courtney Love admitted to seeing Rid as "a far superior record" compared to theirs.[45] In a 2022 MusicRadar interview, Gavin Rossdale of Bush dubbed it "a groundbreaking record from a groundbreaking artist", feeling that "the earthiness [and] truth of it are just fucking too good."[46]

Tour

[edit]Harvey and her band toured in the spring and summer of 1993 to support Rid of Me. The tour began in the UK in May and moved to America in June. Maria Mochnacz documented aspects of the tour, and her footage was used to create the long-form video Reeling with PJ Harvey (1994). Harvey's concert setlist drew from Dry and Rid of Me, but also highlighted songs that did not appear on either of those recordings. For example, she regularly performed a cover version of Willie Dixon's 1961 song "Wang Dang Doodle". One reviewer praised Harvey's version and called it "perhaps the definitive version of that song."[9]

In August, they finished the tour with a string of dates opening for the Irish rock band U2 during their Zooropa tour. In the fall the trio started to disintegrate, first with the departure of Ellis and then Vaughan shortly afterward. By September, Harvey was performing as a solo artist.[47]

Accolades

[edit]Rid of Me entered the UK Albums Chart at number three and quickly went silver, and enjoyed a top-30 hit in the single "50 ft. Queenie". In the US it generated major college-radio airplay and expanded her growing fan base. It also won considerable critical acclaim and featured in various top ten album-of-the-year lists in respectable press, like The Village Voice, Spin, Melody Maker, Vox and Select. Spin gave it a rare ten out of ten review rating. Rid of Me was shortlisted for the 1993 Mercury Prize, but lost to Suede. If anything its critical stature has grown over the years—Rolling Stone selected it as one of the Essential Recordings of the 90s, and in 2005, Spin ranked it the ninth greatest album of 1985–2005[42] after it had ranked it only the 37th greatest album of the 90s after To Bring You My Love at number 3.[48] In 2003, the album was ranked number 405 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time;[49] the list's 2012 edition had it ranked 406th.[50] In 2011, Slant Magazine ranked Rid of Me as the 25th greatest album of the 90s.[51] In 2014, the album placed tenth on the Alternative Nation site's "Top 10 Underrated 90’s Alternative Rock Albums" list.[52] The title track was ranked #194 on the 2021 version of Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.[53]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks are written by Polly Jean Harvey, except "Highway 61 Revisited", written by Bob Dylan. All tracks produced by Steve Albini, except "Man-Size Sextet", produced by PJ Harvey, Rob Ellis and Head.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Rid of Me" | 4:28 |

| 2. | "Missed" | 4:25 |

| 3. | "Legs" | 3:40 |

| 4. | "Rub 'til It Bleeds" | 5:03 |

| 5. | "Hook" | 3:57 |

| 6. | "Man-Size Sextet" | 2:18 |

| Total length: | 23:51 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 7. | "Highway 61 Revisited" (Bob Dylan cover) | 2:57 |

| 8. | "50ft Queenie" | 2:23 |

| 9. | "Yuri-G" | 3:28 |

| 10. | "Man-Size" | 3:16 |

| 11. | "Dry" | 3:23 |

| 12. | "Me-Jane" | 2:42 |

| 13. | "Snake" | 1:36 |

| 14. | "Ecstasy" | 4:26 |

| Total length: | 24:11 (48:02) | |

Personnel

[edit]All personnel credits adapted from Rid of Me's liner notes.[54]

PJ Harvey Trio

- PJ Harvey – vocals, guitar, organ, cello, violin, producer (6)

- Steve Vaughan – bass

- Rob Ellis – drums, percussion, backing vocals, arrangement, producer (6)

Technical

- Steve Albini – producer, engineering, mixing

- Head – producer, engineer (6)

- John Loder – mastering

Design

- Maria Mochnacz – photography

Charts

[edit]

|

Singles[edit]

|

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[65] | Silver | 200,000[64] |

| United States | — | 207,000[66] |

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Award - bpi". BPI. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ Smith, Troy L. (16 October 2019). "75 best albums by Rock and Roll Hall of Fame snubs". Cleveland.com. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Mueller, Andrew. "PJ Harvey - Let the England Shake". Uncut. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ^ Terich, Jeff (30 April 2018). "The punishing primal scream of PJ Harvey's Rid of Me". Treble. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Thompson, Stephen (29 March 2002). "PJ Harvey: Is This Desire?". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "'Rid of Me': The birth of PJ Harvey as an auteur". 4 May 2023.

- ^ Maestri, Cathy (15 July 1993). "PJ Harvey is Taking No Prisoners". The Press-Enterprise.

- ^ Rees, Dafydd; Crampton, Luke (1999). VH1 Rock Stars Encyclopedia. London, England: DK Adult. ISBN 978-0789446138.

- ^ a b c d e Sullivan, Caroline (1 October 1993). "Good golly, Ms Polly; Screeching harridan? Feminist heroine? One thing's certain: Polly Jean Harvey's tortured song-tantrums are a far cry from Captain Beefheart". The Guardian.

- ^ Describing her eating habits in the Guardian article, Harvey said "I wasn't being healthy when I lived in London. I wanted to have complete control of myself, and I thought, in my twisted mind, that I could not eat for three days and still function"

- ^ a b Fay, Liam (19 April 1995). "Polly Unsaturated". Hot Press. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ^ Reynolds, Simon; Press, Joy (1995). The Sex Revolts: Gender, Rebellion, and Rock 'n' Roll. Harvard University Press. p. 339. ISBN 0-674-80272-1.

- ^ a b Sandall, Robert (2 May 1993). "Just Like a Woman". The Sunday Times. London. Features section.

- ^ Giles, Jeff (3 May 1993). "Move Over Tarzan, PJ Harvey is Back". Newsweek. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ Cavanagh, Dave (25 February 1995). "Nemesis in a Scarlet Dress". The Independent. London. Magazine section, p. 30.

- ^ Albini does not like to be credited as "producer" on the albums he records. He prefers the term "sound engineer" or asks to be given a "recorded by" credit.

- ^ a b Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Appearance on MTV's 120 Minutes, interviewed by Lewis Largent, June 20, 1993". Retrieved 30 August 2010 – via YouTube.

- ^ Quoted from Reeling With PJ Harvey, Vision Video Ltd., 1994

- ^ "Maria Mochnacz official website". Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Rid of Me – PJ Harvey". AllMusic. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ Thomas, David (7 May 1993). "Rid of Me". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (2 May 1993). "PJ Harvey's Impassioned Return". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ Rogers, Jude (November 2020). "Raw power". Mojo. No. 324. p. 94.

- ^ Page, Betty (24 April 1993). "Welcome to the Haemorrhage". NME. p. 29.

- ^ Berman, Judy (16 September 2018). "PJ Harvey: Rid of Me". Pitchfork. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ Rigby, Paul (September 2008). "Rid Of Me | PJ Harvey". Record Collector. No. 353. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ Kot, Greg (10 June 1993). "Rid Of Me". Rolling Stone. No. 658. p. 68. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ Hoard, Christian (2004). "PJ Harvey". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 367–368. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1 June 1993). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ^ Bennun, David; Ngaire-Ruth (17 April 1993). "Polly's Got a Cracker". Melody Maker. p. 29.

- ^ Duffy, Thom (6 March 1993). "Eager Fans Await Sophomore Disc by PJ Harvey". Billboard. Vol. 105, no. 10. p. 1. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ Snyder, Michael (14 July 1993). "PJ Harvey Wails Musical Anguish". San Francisco Chronicle. p. D1.

- ^ McDonnell, Evelyn (May 1993). "PJ Harvey: Rid of Me". Spin. Vol. 9, no. 2. p. 79. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Lips, Hips, Tits, Power; PJ Harvey, Björk, Tori Amos". Q. May 1994. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ Romandetta, Julie (7 May 1993). "Brit singer Polly Harvey pours out her rage in a furious punk sound". The Boston Herald. Scene section, p.S14.

- ^ Dollar, Steve (15 May 1993). "PJ opens a wound and lets it bleed". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Leisure section, p.26.

- ^ Gilbey, Ryan (10 March 1995). "Beyond the art of darkness; PJ Harvey/Tricky Cambridge Corn Exchange". The Independent. London. Music/Pop section, p. 31.

- ^ DeRogatis, Jim (9 June 1995). "Harvey Prefers Practicing to Preaching". Chicago Sun-Times. Weekend section, p.5.

- ^ Schonfeld, Zach (20 April 2016). "PJ Harvey Albums From Worst To Best". Stereogum. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ Coffman, Tim (11 February 2022). "20 albums that paved the way for alternative as we know it". Alternative Press. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ a b Johnston, Emma (10 May 2023). "PJ Harvey: the making of Rid Of Me". Louder Sound. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ a b Ganz, Caryn (July 2005). "100 Greatest Albums 1985-2005: 9 PJ Harvey Rid of Me". Spin. Vol. 21, no. 7. p. 71. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Diver, Mike (2009). "BBC - Music - Review of PJ Harvey - Rid of Me". BBC Music. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ Itkowsky, Liz (3 May 2023). "Rediscover PJ Harvey's 'Rid of Me' (1993) | Tribute". Albumism. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ Hopper, Jessica (14 April 2014). "You Will Ache Like I Ache: The Oral History Of Hole's 'Live Through This'". Spin. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Rogers, Ellie (10 October 2022). "Bush's Gavin Rossdale on the 10 albums that changed his life, spending time with Prince and being inspired by PJ Harvey to buy Joe Walsh's Jazzmaster". MusicRadar. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ On 24 September 1993 Harvey appeared on The Tonight Show and performed the song "Rid of Me" using only her guitar and voice.

- ^ Weisbard, Eric (September 1999). "The 90 Greatest Albums of the '90s: 37 PJ Harvey Rid of Me". Spin. Vol. 15, no. 9. p. 138. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Levy, Joe; Steven Van Zandt (2006) [2005]. "405 | Rid of Me - PJ Harvey". Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time (3rd ed.). London: Turnaround. ISBN 1-932958-61-4. OCLC 70672814. Archived from the original on 16 January 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2006.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 31 May 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ "Best Albums of the '90s: 25. PJ Harvey, Rid of Me". Slant Magazine. 14 February 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ Prato, Greg (2 October 2014). "Top 10 Underrated 90's Alternative Rock Albums - AlternativeNation.net".

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. 15 September 2021.

- ^ Rid of Me (Media notes). PJ Harvey. Island Records. 1993. 514 696-2.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "PJ Harvey Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "PJ Harvey Chart History (Heatseekers Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – PJ Harvey – Rid of Me" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – PJ Harvey – Rid of Me" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – PJ Harvey – Rid of Me" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Vinyl 2020 uke 35" (in Norwegian). topplista.no. 28 August 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – PJ Harvey – Rid of Me". Hung Medien. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "full Official Chart History". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "PJ Harvey". Udiscovermusic. 8 April 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ "British album certifications – PJ Harvey – Rid of Me". British Phonographic Industry.

- ^ "Ask Billboard | Billboard.com". Billboard. Retrieved 9 October 2024.