Paul Bernardo

Paul Bernardo | |

|---|---|

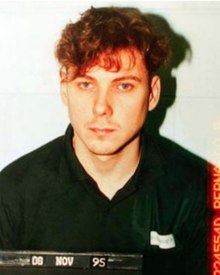

Mugshot of Bernardo taken by Kingston Penitentiary, November 1995 | |

| Born | Paul Kenneth Bernardo August 27, 1964 Scarborough, Ontario, Canada |

| Other names |

|

| Spouse | |

| Conviction(s) |

|

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment with a possibility of parole after 25 years, including a dangerous offender designation, in 1995 |

| Details | |

| Victims | 3 killed; at least 14 raped and 6 attempted to rape |

Span of crimes | May 4, 1987 – April 19, 1992 |

| Country | Canada |

Date apprehended | February 17, 1993 |

| Imprisoned at |

|

Paul Kenneth Bernardo (born August 27, 1964), also known as Paul Jason Teale,[2][3] is a Canadian serial rapist and serial killer dubbed the Scarborough Rapist, the Schoolgirl Killer and, together with his former wife Karla Homolka, one of the Ken and Barbie Killers. He is known for initially committing a series of rapes in Scarborough, Ontario, a district of Toronto, between 1987 and 1990, before committing three murders with Homolka; among these victims was Karla's younger sister, Tammy Homolka.

After his capture and conviction, Bernardo was sentenced to life imprisonment and was declared a dangerous offender, thus making it unlikely that he will ever be released from prison. Following his conviction, Bernardo confessed to ten more rapes committed a year before the spree ascribed to the Scarborough Rapist. Homolka was given a lighter sentence in exchange for testifying against Bernardo as part of a controversial plea bargain; she was released from prison in 2005.

Early life

[edit]Paul Bernardo was born in Scarborough, Ontario, near Toronto, on August 27, 1964, the third and youngest child of Kenneth Walter Bernardo and Marilyn Elizabeth Bernardo (née Eastman).[4] Bernardo's father often sexually abused his older sister, Debra, in front of other family members, and would eventually be charged with crimes involving voyeurism and pedophilia.[5] Bernardo's mother often withdrew from her family due to depression and agoraphobia, eventually moving into the basement.[6]

Bernardo presented himself as being a happy and well-adjusted child despite his family's dysfunction, and was an active member of Scouts Canada.[6] Beneath the charming façade, however, he gradually developed pyromaniac inclinations and dark sexual fantasies, one of which involved creating a "virgin farm" where he would breed virgin girls to rape.[5]

After a fight between his parents in 1981, Bernardo, then aged 16, was informed by his mother that he was the result of an extramarital affair and that Kenneth was not his biological father.[5] Repulsed, Bernardo began to call his mother a "slut" and a "whore"; she reciprocated by calling him a "bastard from hell".[6] Later, after growing weary of his domineering behavior, Bernardo's first girlfriend left him for one of his friends.[4] In retaliation, Bernardo set fire to all of her belongings to which he had access.[5]

Bernardo attended Sir Wilfrid Laurier Collegiate Institute and, in 1982, the University of Toronto Scarborough (UTSC), where another notorious Canadian murderer, Russell Williams, was coincidentally two academic years behind him.[5] As his day job, Bernardo worked for Amway, the sales culture of which deeply affected him.[7]

Bernardo and his college friends practised pickup techniques on young women they met in bars and were fairly successful.[8] Bernardo delighted in humiliating his dates in public and engaging in aggressive anal intercourse in bed. His relationships became increasingly violent and unstable, and he threatened to kill his partners if they disclosed the abuse.[6] In 1986, Bernardo was served with restraining orders by two women after he made obscene phone calls.[4]

In October 1987, Bernardo met Karla Homolka while she was visiting Scarborough to attend a pet store conference. The two shared an immediate attraction, as Homolka encouraged Bernardo's sadistic sexual behavior.[6]

Scarborough Rapist cases

[edit]Between 1987 and 1990, Bernardo committed increasingly vicious serial rapes in and around Scarborough.[9] He attacked most of his victims after stalking them as they got off buses late in the evening. Known incidents are:

- May 4, 1987: Rape of a 21-year-old Scarborough woman in front of her parents' house after Bernardo followed her home.[10]

- May 14, 1987: Rape of a 19-year-old woman in the backyard of her parents' house.[11]

- July 17, 1987: Attempted rape of a young woman. Although he beat the victim, Bernardo abandoned the attack when she fought back.[11]

- September 29, 1987: Attempted rape of a 15-year-old girl. Bernardo broke into the victim's house and entered her bedroom. He jumped on her back, put his hand over her mouth, threatened her with a knife, bruised the side of her face and bit her ear. Bernardo fled when the victim's mother entered the room and screamed. Anthony Hanemaayer was wrongfully convicted of the assault in 1989 and served a sixteen-month prison sentence, but was exonerated after Bernardo admitted to the crime in 2006.[12]

- December 16, 1987: Rape of a 15-year-old girl. The next day, the Toronto Police Service issued a warning to women in Scarborough traveling alone at night, especially those riding buses.[11]

- December 23, 1987: Rape of a 17-year-old girl with a knife he used to threaten his victims. At this point, he began to be known as the Scarborough Rapist.[11]

- April 18, 1988: Attack of a 17-year-old girl.[13]

- May 25, 1988: Bernardo was nearly caught by a uniformed police officer staking out a bus shelter. Although the officer noticed him hiding under a tree and pursued him on foot, Bernardo escaped.[13]

- May 30, 1988: Rape of an 18-year-old woman in Mississauga, Ontario, about 40 kilometres (25 miles) southwest of Scarborough.[13]

- October 4, 1988: Attempted rape in Scarborough. Although his intended victim fought him off, Bernardo inflicted two stab wounds to her thigh and buttock which required twelve stitches.[13]

- November 16, 1988: Rape of an 18-year-old woman in the backyard of her parents' house.[13]

- November 17, 1988: Police formed a task force to capture the Scarborough Rapist.[13]

- December 27, 1988: Attempted rape, with a neighbour chasing Bernardo off.[13]

- June 20, 1989: Attempted rape; the young woman fought, and her screams alerted neighbours. Bernardo fled with scratches on his face.[13]

- August 15, 1989: Rape of a 22-year-old woman.[13]

- November 21, 1989: Rape of a 15-year-old girl Bernardo saw in a bus shelter.[13]

- December 22, 1989: Rape of a 19-year-old woman.[13]

- May 26, 1990: Rape of a 19-year-old woman. The victim's vivid recollection of her attacker enabled police to create a computer composite portrait, which was released two days later by police and publicized in Toronto and surrounding areas.[13]

Investigation and release

[edit]In July 1990, two months after police received tips that Bernardo resembled the Scarborough Rapist composite, he was interviewed by two police detectives.[13] From May to September 1990, Toronto police submitted more than 130 suspects' samples for DNA testing. Investigators received two tips pointing to Bernardo. The first, in June, had been filed by a bank employee. The second was from Tina Smirnis, wife of one of the three Smirnis brothers who were among Bernardo's closest friends. Smirnis told detectives that Bernardo "had been 'called in' on a previous rape investigation – once in December 1987 – but he had never been interviewed".[7] Bernardo frequently talked about his sex life to Smirnis and said that he liked rough sex.[7] Police interviewed Bernardo on November 20, 1990, for thirty-five minutes. Bernardo voluntarily provided DNA samples for forensic testing. When the detectives asked Bernardo why he thought he was being investigated for the rapes, he admitted that he resembled the composite. Reportedly, detectives found Bernardo more credible than Smirnis.[7]

Schoolgirl Killer murders

[edit]Tammy Homolka

[edit]By 1990, Bernardo had lost his job as an accountant and was smuggling cigarettes across the nearby Canada–United States border. He spent long periods of time with Homolka's family, who liked him and were unaware of his criminal activities. Although he was engaged to Karla, he had become obsessed with her younger sister Tammy, peering into her window and entering her room to masturbate while she slept. Karla helped Bernardo by breaking the windows in her sister's room, allowing him access. According to Bernardo's testimony at trial, Karla laced spaghetti sauce with crushed valium she had stolen from her employer at an animal clinic. She served it to her sister, who soon lost consciousness. Bernardo then raped Tammy while Karla watched. After one minute, Tammy regained consciousness.[7][14]

Six months before their 1991 wedding, Karla stole the anesthetic agent halothane from the clinic. On December 23, 1990, Karla and Bernardo administered sleeping pills to 15-year-old Tammy in a rum-and-eggnog cocktail. When Tammy lost consciousness, Karla and Bernardo undressed her and Karla applied a halothane-soaked cloth to her sister's nose and mouth. Karla wanted to "give Tammy's virginity to Bernardo for Christmas"; according to her, Bernardo was disappointed that he was not Karla's first sex partner. With Tammy's parents sleeping upstairs, the couple videotaped themselves raping Tammy in the basement. Tammy began to vomit; they tried to revive her and called 9-1-1 after hiding evidence, dressing Tammy and moving her into her bedroom. A few hours later, Tammy was pronounced dead at St. Catharines General Hospital without regaining consciousness.[15]

Despite being observed vacuuming and washing laundry in the middle of the night,[7] and despite a chemical burn on Tammy's face, the Regional Municipality of Niagara coroner and Karla's family accepted the couple's version of events.[7] The official cause of Tammy's death was ruled accidental, the result of choking on vomit after consumption of alcohol. After Tammy's death, Bernardo and Karla videotaped themselves engaging in sexual intercourse, with Karla wearing Tammy's clothing and pretending to be her. They moved out of the Homolka house to a rented bungalow in Port Dalhousie to allow Karla's parents to grieve.[16]

In 2001, the magazine Elm Street published an article in which it implied that forensic evidence proved that Tammy's death was not an accident and that her sister had deliberately administered an overdose of Halothane. The publication described Karla as a "malignant narcissist" who was so incensed by her fiancé's attraction to her sister that she removed Tammy from his affections permanently.[17]

Leslie Mahaffy

[edit]Early in the morning on June 15, 1991, while detouring through Burlington to steal licence plates, Bernardo came across 14-year-old Leslie Mahaffy.[18] Mahaffy had been locked out of her house for missed curfew after attending a friend's wake. Bernardo left his car and approached Mahaffy, saying that he wanted to break into a neighbour's house. Unfazed, she asked if he had any cigarettes. When Bernardo led her to his car, he blindfolded her, forced her into the car, drove her to Port Dalhousie, and informed Homolka that they had a victim.[19]

Bernardo and Homolka videotaped themselves torturing and sexually abusing Mahaffy while they listened to pop music. At one point, Bernardo said, "You're doing a good job, Leslie, a damned good job", adding: "The next two hours are going to determine what I do to you. Right now, you're scoring perfect."[19] On another segment of tape played at Bernardo's trial, the assault escalated. Mahaffy cried out in pain and begged Bernardo to stop. In the Crown description of the scene, he was sodomizing her while her hands were bound with twine.[19]

Mahaffy later told Bernardo that her blindfold seemed to be slipping, which signaled the possibility that she could identify her attackers if she lived. The following day, Bernardo claimed, Homolka fed her a lethal dose of Halcion; Homolka claimed that Bernardo strangled her. They put Mahaffy's body in their basement the day before Homolka's family had dinner at the house.[19]

Following the dinner party, Bernardo and Homolka decided to dismember Mahaffy's body and encase each part of her remains in cement. Bernardo bought a dozen bags of cement at a hardware store the following day; he kept the receipts, which were damaging at his trial. After Bernardo cut apart the body using his grandfather's circular saw, the couple made a number of trips to dump the cement blocks in Lake Gibson, 18 kilometres (11 mi) south of Port Dalhousie. At least one of the blocks weighed 90 kg (200 pounds) and was beyond their ability to sink. It lay near the shore, where it was found on June 29, 1991, coincidentally on Bernardo and Homolka's wedding day.[20] Mahaffy's orthodontic appliance was instrumental in identifying her.

Several days before Homolka's release from prison in July 2005, Bernardo was interviewed by police and his lawyer, Tony Bryant. According to Bryant, Bernardo stated that he had always intended to free the girls he and Homolka had kidnapped. However, when Mahaffy's blindfold fell off, Homolka was concerned that Mahaffy would identify Bernardo and report the couple to the police. Bernardo claimed that Homolka planned to murder Mahaffy by injecting an air bubble into her bloodstream, triggering an air embolism.[21]

Kristen French

[edit]During the after-school hours of April 16, 1992, Bernardo and Homolka drove through St. Catharines to look for potential victims. Although students were still going home, the streets were generally empty. As they passed Holy Cross Secondary School, the couple spotted 15-year-old Kristen French walking home.[22] After they pulled into the parking lot of nearby Grace Lutheran Church, Homolka got out of the car carrying a map, pretending to need assistance. When French looked at the map, Bernardo attacked from behind and forced her into the front seat of the car at knifepoint. From the back seat, Homolka subdued French by pulling her hair.[23][7]

After French failed to arrive home, her parents became convinced that she met with foul play and notified police. Within twenty-four hours the Niagara Regional Police Service (NRP) assembled a team, searched French's after-school route and found several witnesses who had seen the abduction from different locations. French's shoe, recovered from the parking lot, underscored the seriousness of the abduction.[23]

Over the Easter weekend, Bernardo and Homolka videotaped themselves torturing, raping and sodomizing French, forcing her to drink large amounts of alcohol and submit to Bernardo. At his trial, Crown prosecutor Ray Houlahan said that Bernardo always intended to kill French because she was never blindfolded and could identify her captors. The following day, Bernardo and Homolka murdered French before going to the Homolkas' for Easter dinner. Homolka testified at her trial that Bernardo strangled French for seven minutes while she watched. Bernardo claimed that Homolka beat French with a rubber mallet because she tried to escape, and French was strangled with a noose around her neck which was secured to a hope chest; Homolka then went to fix her hair.[24]

French's nude body was found on April 30, 1992, in a ditch in Burlington, about forty-five minutes from St. Catharines and a short distance from the cemetery where Mahaffy is buried. She had been washed and her hair was cut off. Although it was thought that the hair was removed as a trophy, Homolka testified that it was cut to impede identification.[25]

Additional victims

[edit]In addition to the three confirmed murders ascribed to Bernardo and Homolka, suspicions remain about other possible victims or intended victims:

- Derek Finkle's 1997 book No Claim to Mercy presented evidence tying Bernardo to the presumed murder of 22-year-old Elizabeth Bain, who disappeared on June 19, 1990.[26] Bain told her mother that she was going to "check the tennis schedule" at UTSC; three days later, her car was found with a large bloodstain on the back seat.[27] Bernardo matched the description of a man in the area where Bain was last seen, and later confessed to at least eight attacks in and around the same location. Bain's boyfriend, Robert Baltovich, was convicted of second-degree murder in her death on March 31, 1992. During his trial and subsequent imprisonment, Baltovich and his lawyers repeatedly alleged that Bernardo was the perpetrator.[28] The Court of Appeal for Ontario set aside Baltovich's conviction on December 2, 2004, and at his retrial on April 22, 2008, the Crown told the court that no evidence would be called against Baltovich and asked the jury to find him not guilty of second-degree murder. When questioned about Bain in 2007, Bernardo said: "The answer to that is no. But the 800 pound gorilla in the room is that it is a life-to-25 sentence."[29]

- Shortly after Tammy Homolka's funeral, her parents left town and her sister Lori visited grandparents in Mississauga, leaving the house empty. According to author Stephen Williams, during the weekend of January 12, 1991, Bernardo abducted a girl, took her to the house, raped her while Karla watched, and dropped her off on a deserted road near Lake Gibson. Bernardo and Homolka called her "January girl".[7]

- At about 5:30 a.m. on April 6, 1991, Bernardo abducted a 14-year-old who was training to be a coxswain for a local rowing team. The girl was distracted by a blonde woman who waved at her from her car, enabling Bernardo to drag her into the shrubbery near the rowing club. He sexually assaulted her, forced her to remove her clothes and made her wait five minutes during which he disappeared.[7]

- On June 7, 1991, Homolka invited to their home a 15-year-old girl (known as "Jane Doe" in the trials) she had befriended at a pet shop two years earlier. After being drugged by Homolka, "Doe" was sexually assaulted by the couple, which was videotaped. In August, "Doe" was invited back to the couple's residence and was again drugged. Homolka called 9-1-1 for help after the girl vomited and stopped breathing while being raped. The ambulance was recalled after Bernardo and Homolka resuscitated her.[30]

- On July 28, 1991, Bernardo stalked Sydney Kershen, aged 21, after he saw her while driving home from work. On August 9, he resumed stalking her. This time, she took evasive action, stopping at her boyfriend's house just prior to his arrival. After spotting Bernardo, the boyfriend gave chase, came across Bernardo's gold Nissan, and took note of the licence plate. The couple reported the incident to the Niagara Regional Police (NRP), which established that the car belonged to Bernardo. An NRP officer visited Bernardo's house and saw the car parked in the driveway, but did not pursue the matter, nor submit an official police report.[7]

- A newspaper clipping found during the police search of Bernardo's house described a rape that occurred in Hawaii during the couple's honeymoon there in the summer of 1991. The article, the rape's similarity to Bernardo's modus operandi, and its occurrence during the couple's presence in Hawaii led police to speculate on Bernardo's involvement. Law enforcement officials in both Canada and the U.S. have stated their belief that Bernardo was responsible for this rape, but due to extradition issues, this case was never prosecuted.[7]

- On November 30, 1991, Terri Anderson, a grade nine student at Lakeport Secondary School (adjacent to French's Catholic school), vanished less than 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from the parking lot where French would later be abducted.[31] In April 1992, the NRP said they had no evidence to suggest a link. Anderson's body was ultimately found in the water at Port Dalhousie.[32] The coroner saw no evidence of foul play, despite the difficulties of determining such factors in a body that had been in the water for six months. The coroner's ruling that her death was by drowning – probably as a result of drinking beer and taking LSD – was controversial in light of the circumstances of the Mahaffy and French murders.[7]

- On March 29, 1992, Bernardo stalked and videotaped sisters Shanna and Kerry Patrich from his car, following them to their parents' house.[33] The sisters incorrectly recorded his licence plate number; Shanna reported the incident to the NRP on March 31, 1992, and was given an incident number should further information develop. On April 18, 1992, while French was still being held captive, Bernardo was spotted by Kerry while he had gone out to buy dinner and rent a movie. Despite failing to track him to his house, Kerry got a better description of his licence plate and car, which she reported to the NRP. This information, however, was mishandled by police.[7]

- In 2006, Bernardo confessed to at least ten more sexual assaults dating back to March 1986,[31] including the 1987 assault of a 15-year-old girl. Another man, Anthony Hanemaayer, had been convicted of the assault and served a full sentence for it. On June 25, 2008, the Court of Appeal for Ontario overturned the conviction and exonerated Hanemaayer.[12]

Investigation and arrest

[edit]Homolka and Bernardo were questioned by police several times in connection with the Scarborough Rapist investigation, Homolka's death, and Bernardo's stalking of other women before French's abduction.[7] On May 12, 1992, Bernardo was briefly interviewed by an NRP sergeant and constable, who decided that he was an unlikely suspect despite his admission that he had previously been questioned in connection to the Scarborough Rapist. Three days later, the Green Ribbon Task Force was created to investigate the murders of Mahaffy and French. Bernardo and Homolka had applied to have their names legally changed to Teale, which Bernardo had taken from the serial killer in the 1988 film Criminal Law. At the end of May, John Motile, an acquaintance of Smirnis and Bernardo, reported Bernardo as a possible suspect in the murders.[7]

In December 1992, the Centre of Forensic Sciences finally began testing DNA samples provided by Bernardo two years earlier. On 27 December, Bernardo severely beat Homolka with a flashlight, leaving multiple bruises. Claiming that she had been in an automobile accident, Homolka returned to work on 4 January 1993.[7] Her skeptical co-workers called her parents, and although they rescued her the following day by physically removing her from Bernardo's house, Homolka went back in to frantically search for something. Homolka's parents took her to St. Catharines General Hospital, where she gave a statement to the NRP that she was a battered spouse and filed charges against Bernardo. He was arrested, and later released on his own recognizance. A friend who found Bernardo's suicide note intervened, and Homolka moved in with relatives in Brampton.[7]

Arrest

[edit]Twenty-six months after Bernardo submitted a DNA sample, Toronto police were informed that it matched that of the Scarborough Rapist and immediately placed him under 24-hour surveillance. Metro Toronto Sexual Assault Squad investigators interviewed Homolka on February 9, 1993. Despite hearing their suspicions about Bernardo, she focused on his abuse of her. Later that night Homolka told her aunt and uncle that Bernardo was the Scarborough Rapist, that she and Bernardo were involved in the rape and murder of Mahaffy and French, and that the rapes were recorded.[34]

The NRP subsequently reopened its investigation of Tammy Homolka's death. Two days later Homolka met with Niagara Falls lawyer George Walker, who sought legal immunity from Crown prosecutor Houlahan in exchange for her cooperation. She was also placed under 24-hour surveillance.[7] The couple's name change was approved on February 13, 1993.[3] The next day, Walker met with Crown Criminal Law Office director Murray Segal. After Walker told Segal about the videotapes, Segal advised him that, due to Homolka's involvement in the crimes, full immunity was not a possibility.[7]

On February 17, detectives arrested Bernardo on several charges and obtained a search warrant. Because his link to the murders was weak, the warrant was limited; no evidence which was not expected and documented in the warrant could be removed from his property, and all videotapes found by police had to be viewed in the house. Damage had to be kept to a minimum; police could not tear down walls looking for the tapes. The search of the house (including updated warrants) lasted 71 days, and the only tape found by police had a brief segment of Homolka performing oral sex on "Jane Doe".[35]

During a call from jail, Bernardo told his lawyer, Ken Murray, that the rape videos were hidden in a ceiling light fixture in the upstairs bathroom. Murray found the tapes and hid them from investigators. After Murray resigned as Bernardo's lawyer, his new attorney, John Rosen, turned the tapes over to police.[36] On May 5, Walker was informed that the government was offering Homolka a plea bargain of twelve years' imprisonment which she had one week to accept. If she declined, the government would charge her with two counts of first-degree murder, one count of second-degree murder and other crimes. Walker accepted the offer, and Homolka later agreed to it. On May 14, Homolka's plea bargain was finalized, and she began giving statements to police investigators. She told police that Bernardo boasted that he had raped as many as thirty women, twice as many as the police suspected.[31]

Publication ban

[edit]Citing the need to protect Bernardo's right to a fair trial, a publication ban was imposed on Homolka's preliminary inquiry.[37] The Crown had applied for the ban, which was imposed on July 5 by Francis Kovacs of the Ontario Court of Justice. Through her lawyers, Homolka supported the ban; Bernardo's lawyers argued that he would be prejudged by the ban, since Homolka had been portrayed as his victim. Four media outlets and one author also opposed the ban. Some lawyers argued that rumours could damage the future trial process more than the publication of evidence.[38] In February 1994, Homolka divorced Bernardo.[39]

Public access to the Internet effectively nullified the court's order, as did proximity to the U.S.-Canada border. American journalists, not subject to the publication ban, published details of Homolka's testimony which were distributed by "electronic ban-breakers".[40] Newspapers in Buffalo, Detroit, Washington, D.C., New York City and the United Kingdom, as well as radio and television stations close to the border, divulged the details. Canadians brought copies of The Buffalo News across the border, prompting orders to the NRP to arrest all those with more than one copy at the border; extra copies were confiscated. Copies of other newspapers, including The New York Times, were turned back at the border or not accepted by distributors in Ontario.[38] Gordon Domm, a retired police officer who defied the publication ban by distributing details from foreign media, was convicted of two counts of contempt of court.[41]

Trial, conviction, and incarceration

[edit]Bernardo was tried for the murders of French and Mahaffy in 1995, and his trial included detailed testimony from Homolka and videotapes of the rapes.[42] Bernardo testified that the deaths were accidental, later claiming that Homolka was the actual killer. On September 1, 1995, Bernardo was convicted of a number of offences, including the two first-degree murders and two aggravated sexual assaults, and sentenced to life in prison without parole for at least twenty-five years.[43] He was designated a dangerous offender, making him unlikely to ever be released.[43]

Homolka's plea bargain was criticized by many Canadians since Bernardo's first defence lawyer, Ken Murray, had withheld the videotapes exposing Homolka's culpability for seventeen months. The videotapes were considered crucial evidence, and prosecutors said that they would never have agreed to the plea bargain if they had seen them. Murray was later acquitted of obstruction of justice and faced a disciplinary hearing by the Law Society of Upper Canada.[44][45]

Although Bernardo was kept in the segregation unit at Kingston Penitentiary for his own safety, he was attacked and harassed; he was punched in the face by another inmate when he returned from a shower in 1996. In June 1999, five convicts tried to storm his segregation range and a riot squad used gas to disperse them.[46]

On February 21, 2006, the Toronto Star reported that Bernardo had admitted sexually assaulting at least ten other women in attacks not previously attributed to him. Most were in 1986, a year before the spree attributed to the Scarborough Rapist. Authorities suspected Bernardo in other crimes, including a string of rapes in Amherst, New York, and the drowning of Terri Anderson in St. Catharines,[47] but he has never acknowledged his involvement. His lawyer, Anthony G. Bryant, reportedly forwarded the information to legal authorities in November 2005.[48]

In 2006, Bernardo gave a prison interview in which he claimed that he had reformed and would make a good parole candidate.[49][50] He became eligible to petition a jury for early parole in 2008 under the faint hope clause (since he committed multiple murders before the 1997 criminal-code amendment) but did not do so. In 2015, Bernardo applied for day parole in Toronto. According to the victims' lawyer, Tim Danson, it is unlikely that Bernardo will ever be released in any capacity due to his dangerous offender status.[51] In September 2013, Bernardo was transferred to Millhaven Institution in Bath, where he was reportedly segregated from other inmates.[52]

In November 2015, Bernardo self-published A MAD World Order, a violent, fictional, 631-page e-book on Amazon.[53] By November 15, the book was reportedly an Amazon bestseller, but was removed from the website due to a public outcry.[54] In October 2018, Bernardo had been set to go to trial for possession of a "shank" weapon while incarcerated. However, the prosecution dropped the charges due to their determination that there was no reasonable probability of conviction.[55]

Bernardo became eligible for parole in February 2018.[56] On October 17 of that year, he was denied day and full parole by the Parole Board of Canada.[57] His next parole hearing took place on June 22, 2021;[58] it took only one hour of deliberation by the presiding judge for his application to be turned down.[59]

In May 2023, after spending a decade at Millhaven Institution, Bernardo was transferred to La Macaza Institution, a medium-security facility in Quebec, where he will continue to serve his indeterminate sentence.[1] The transfer caused controversy and initially the reason for the transfer was not provided to the public. Bernardo had successfully applied to be moved there.[60] In light of the scandal and dismay raised by the transfer, on June 5, 2023, Correctional Service Canada announced it was to review the decision[61] and on July 20, Commissioner Anne Kelly explained in a 30-minute press conference that the review board found the transfer to be "sound" in view of the passage of Bill C-83,[62] An Act to amend the Corrections and Conditional Release Act and another Act.[63]

On July 26, 2023, Public Safety Minister Marco Mendicino was dropped from cabinet and replaced by Dominic LeBlanc during a cabinet shuffle with the media attributing his demotion to the controversy around the Bernardo transfer.[64] The day after LeBlanc was installed, The Globe and Mail wrote an article covering his opinion that the legislation was inconsequential,[65] while Pierre Poilievre, the Leader of the Opposition, said that this was an example of the soft-on-crime policies of the Trudeau government.[66]

On October 25, 2023, Bernardo's next parole hearing was scheduled for February 2024.[67] On March 6, 2024, MP Frank Caputo learnt there was an inmate hockey rink on the premises of La Macaza. Caputo said "the cherry on top was seeing this beautiful gymnasium and next to that is a weight room. Much nicer than 95 per cent of Canadians have access to."[68]

Law-enforcement review

[edit]After Bernardo's 1995 conviction, the Ontario government appointed Archie Campbell to review the roles played by the police services during the investigation. In his 1996 report, Campbell found that a lack of coordination, cooperation and communications by police and other elements of the judicial system contributed to a serial predator "falling through the cracks".[33] One of Campbell's key recommendations was for an automated case-management system for Ontario's police services to use in investigations of homicides and sexual assaults. Ontario is the only place in the world with this type of computerized case-management network. Since 2002, all municipal police services and the Ontario Provincial Police have had access to this network, known as PowerCase.[33]

Psychology

[edit]Bernardo scored 35 out of 40 on the Psychopathy Checklist, a psychological assessment tool used to assess the presence of psychopathy in individuals.[69] This is classified as clinical psychopathy.[70] Homolka, by contrast, scored 5 out of 40. At his October 17, 2018, parole meeting, evidence from expert psychiatric reports found that he had "deviant sexual interests and [he] met the diagnostic criteria of sexual sadism, voyeurism, and paraphilia not otherwise specified." The reports furthermore stated that he "met the criteria for narcissistic personality disorder and [met the requirement for] a diagnosis of psychopathy," meaning he was thereby "more likely to repeat violent sexual offending." The reports concluded that Bernardo "showed minimal insight into [his] offending, which is consistent with file information that suggests [he] has been keen over the years to come up with [his] own unsubstantiated reasons for [his] criminal behaviour."[71]

In popular culture

[edit]Television and film

[edit]- Episodes of Law & Order ("Fools for Love", season 10),[72] Law & Order: Special Victims Unit ("Damaged", season 4 and "Pure", season 6), Close to Home ("Truly, Madly, Deeply", season 2) and The Inspector Lynley Mysteries (2007's "Know Thine Enemy") were inspired by the case.

- The second episode of The Mentalist concerned a respectable, murderous husband-and-wife team.

- The Criminal Minds episode "Mr. and Mrs. Anderson" contains a serial-killer couple loosely based on Bernardo and Homolka, and the Bernardo case was mentioned by the Behavioral Analysis Unit team when they delivered their profile to the local police.

- Dark Heart, Iron Hand, an MSNBC documentary rebroadcast as "To Love and To Kill" on MSNBC Investigates, concerned the case.[73][74]

- In 2004, producers from Quantum Entertainment (a Los Angeles-based production company) announced the release of Karla, with the working title Deadly. Misha Collins portrayed Bernardo in the film alongside Laura Prepon, who starred as Karla Homolka.[75]

- Another documentary aired on the Discovery+ streaming service via the sub-channel Investigation Discovery entitled The Ken & Barbie Killers: The Lost Tapes.[76] It premiered on December 12, 2021, and consisted of 4 episodes.

Music

[edit]- The 1993 Rush song "Nobody's Hero" references the murder of a young girl in Port Dalhousie, drummer Neil Peart's hometown.[77]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b MacAlpine, Ian (June 2, 2023). "Notorious child killer Paul Bernardo transferred to Quebec institution". Montreal Gazette. Postmedia News. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- ^ "What's on the Bernardo Tape?".

- ^ a b "Name Change Apparently Was Quick and Easy Task for Teale". June 13, 1993.

- ^ a b c "Bernardo, Paul" (PDF). maamodt.asp.radford.edu. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Fowles, Stacy May (November 11, 2013). "Boy Next Door". The Walrus. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Pron, Nick (2005). Lethal Marriage: The Uncensored Truth Behind the Crimes of Paul Bernardo and Karla Homolka. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Seal Books. ISBN 0-7704-2936-X. OCLC 60738933. Archived from the original on October 9, 2023. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Williams, Stephen (2009). Invisible Darkness: The Strange Case of Paul Bernardo and Karla Homolka. Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-56965-3.

- ^ Bardsley, Marilyn. "Paul Bernardo & Karla Homolka". truTV. Archived from the original on April 10, 2008. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ^ Butts, Edward (June 21, 2016). "Paul Bernardo and Karla Homolka Case". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- ^ Dimuro, Gina (December 10, 2021). "Meet The Ken And Barbie Killers: Paul Bernardo And Karla Homolka". allthatsinteresting.com. Archived from the original on May 24, 2022. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Bernardo, Paul" (PDF). maamodt.asp.radford.edu. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "Court clears Ontario man after Bernardo confession". CBC. June 25, 2008. Archived from the original on June 28, 2008. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Bernardo, Paul" (PDF). maamodt.asp.radford.edu. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Barry (June 10, 1995). "Bernardo Note Found in Casket". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ Mackie, Richard (November 20, 2002). "Homolka plea deal in doubt". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on April 29, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ Jenish, D'Arcy (March 17, 2003). "Homolka's Plea Bargain Revealed". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ Trish Wood (April 2001). "The Case Against Karla". Elm Street Magazine.

- ^ Jenish, D Arcy (May 29, 1995). "Horror stories". Maclean's Magazine Vol.108, Iss. 22. Rogers Publishing Limited. pp. 14–18. ProQuest 218451932.

- ^ a b c d Deadly Innocence at pp. 5-6, 20-27, 317-320, 520-524.

- ^ Blackden, Patrick; Gould, Russell (2002). "The Ken and Barbie Killers". My Bloody Valentine. London, England: Virgin Books Ltd. p. 212.

- ^ "Bernardo's lawyer says killer 'agitated' over attention given to Homolka". CBC. July 5, 2005. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ Douglas, John E. (October 17, 2019). Journey into Darkness: Follow the FBI's Premier Investigative Profiler as He Penetrates the Minds and Motives of the Most Terrifying Serial Killers. Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-1-78746-514-5. OCLC 1126254005.

- ^ a b Flowers, R. Barri (January 13, 2017). Murder and Menace: Riveting True Crime Tales (Vol. 1). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-5425-3065-1. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Bernardo Trial Gets Underway Archived February 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hewitt, Bill, Weinstein, Fannie (September 18, 1995). "Record of horror". People Weekly, 1995. Vol. 44, Iss. 12. Time, Inc., New York. pp. 235–239. ProQuest 204348708.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Finkle, Derek (1997). No Claim to Mercy: Elizabeth Bain And Robert Baltovich, a Suburban Mystery. Toronto: Viking. ISBN 0-670-87412-4. OCLC 78820165.

- ^ "Elizabeth Marie Bain". Doe Network. Archived from the original on December 30, 2011. Retrieved May 1, 2013.

- ^ "Baltovich trial timeline". CBC News. April 22, 2008. Archived from the original on April 10, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ^ "Bernardo asks to talk to police about Bain case". CBC News. June 7, 2007. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ^ Lorraine Leafloor, Kathrine (1997). Investigating Gender Bias and Sentencing Disparity A Case Study Analysis of the Paul Bernardo Karla Homolka Case (PDF) (Report). National Library of Canada. pp. 133–141. ISBN 0-612-22091-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 4, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c Pron, Nick (February 21, 2006). "Bernardo admits more rapes". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ^ "Bernardo, Paul" (PDF). maamodt.asp.radford.edu. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c Ontario, Province of. "Ontario Major Case Management". Ontario Major Case Management. Province of Ontario. Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ Crary, David (June 19, 1995). "Ex-Wife Completes Horrific Account Of Teenagers' Sex Murders". Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 26, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ "Paul Bernardo's former lawyer continues his testimony". CBC News. April 18, 2000. Archived from the original on September 4, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Canadian Killers Part II: Be warned, the details are graphic and brutal". thechive.com. October 16, 2015. Archived from the original on October 9, 2023. Retrieved October 3, 2022.

- ^ "Bernardo Trial Gets Underway". The Canadian Encyclopedia Historica. Maclean's. Archived from the original on February 6, 2009. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ a b Farnsworth, Clyde H. (December 10, 1993). "Murder Trial in Canada Stirs Press Freedom Fight". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ Crary, David (June 19, 1995). "Ex-Wife Completes Horrific Account Of Teenagers' Sex Murders". Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 26, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ Dov Wisebrod. "The Homolka Information Ban". wisebrod.com. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ Gordon Domm. "Our Most Serious Consideration — Consent 24 - December 1995". Freedom Party International. Archived from the original on July 29, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ Jenish, D'Arcy (September 11, 1995). "Bernardo Convicted". Maclean's. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ^ a b "R. v. Bernardo, 1995, O.J. No. 2988 (Ct. J. (Gen. Div.))" (PDF). Martenslingard.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 20, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ The Ken Murray Case: Defence Counsel's Dilemma. "The Ken Murray Case: Defence Counsel's Dilemma". Criminal Defence News - Cooper & Sandler LLP. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ "Court finds Bernardo lawyer not guilty". Cbc.ca. November 10, 2000. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ Hewitt, Pat (October 24, 2010). "Russell Williams enters a 'grim' existence in Kingston Penitentiary". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- ^ Pron, Nick (February 21, 2006). "Bernardo admits more rapes". Toronto Star.

- ^ "Bernardo confessed to more crimes: lawyer". CBC. February 21, 2006. Archived from the original on August 24, 2007. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ "Bernardo Says He's A Good Candidate For Parole". CityNews. June 10, 2008. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ^ "Paul Bernardo Interview Tape". CityNews. June 21, 2008. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ^ "Families of victims devastated Paul Bernardo has applied for day parole". Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Warmington, Joe (September 26, 2013). "Paul Bernardo dad says Karla Homolka 'got away with it'". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on August 14, 2015. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ "Paul Bernardo publishes violent e-book on Amazon: report". CBC News. November 12, 2015. Archived from the original on November 13, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ "Book by Paul Bernardo no longer available on Amazon". Archived from the original on August 31, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Killer Paul Bernardo set for weapon trial". The Record. October 5, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2018.[dead link]

- ^ "Ontario killer and rapist Paul Bernardo denied parole". CBC News. October 17, 2018. Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ Perkel, Colin (October 17, 2018). "Killer-rapist Paul Bernardo denied day and full parole". Toronto Star. The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ Turnbull, Sarah (June 2, 2021). "Next parole hearing for Paul Bernardo set for June 22". CTV News. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ Colin Perkel (June 22, 2021). "No parole for teen killer Paul Bernardo". Winnipeg Free Press. The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ "Paul Bernardo to stay in medium-security prison as correctional service defends transfer". CP24. July 20, 2023. Archived from the original on July 21, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Stephanie (June 5, 2023). "Prison service to review decision to transfer killer Bernardo to medium security". CTV News. Archived from the original on June 6, 2023. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ "Correctional Service Canada provides update on Paul Bernardo medium-security prison transfer". CP24. July 20, 2023.

- ^ "Legislative Summary of Bill C-83: An Act to amend the Corrections and Conditional Release Act and another Act". Library of Parliament. October 30, 2018.

- ^ "Evening Update: Justin Trudeau retools his cabinet in a major shuffle". Globe and Mail. July 26, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Public Safety department says 2019 Liberal bill did not affect Bernardo's transfer". The Globe and Mail. July 27, 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Stephanie (July 27, 2023). "Ottawa denies Bernardo transfer was due to Liberal law, points to Harper era". CTV News. The Canadian Press.

- ^ "Prison officials 'intervened' to stop Paul Bernardo from making public statement". CTV News. October 25, 2023. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ^ "Conservative, Bloc MPs prompt 'emergency' probe of Paul Bernardo's prison conditions". CBC.ca. March 6, 2024. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ "The Psychopath Next Door". Doc Zone. Season 2014-15. Episode 7. November 27, 2014. 3 minutes in. CBC Television. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ "The Psychopath Next Door: The Psychopathy Checklist". Doc Zone. CBC/Radio Canada. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Staff, The Star (June 22, 2021). "The victim impact statements of Donna French and Debbie Mahaffy, mothers of Paul Bernardo's teen victims". thestar.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ "Bernardo murders inspire Law & Order episode". CBC News. November 10, 1999. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ "Weekend Primetime on MSNBC". Mail-archive.com. May 31, 2002. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Television News, Reviews and TV Show Recaps - HuffPost TV". Television.aol.com. Archived from the original on July 15, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Homolka movie to debut at Montreal film fest". Archived from the original on April 20, 2007. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- ^ "The Ken & Barbie Killers: Where is Karla Homolka Today?". Archived from the original on December 13, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ Defnael, Aka (December 5, 2015). Rush Archive (in French). Camion Blanc. ISBN 9782357797758. Archived from the original on October 9, 2023. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Crosbie, Lynn (1997). Paul's Case: The Kingston Letters. Insomniac Press. ISBN 1-895837-09-X.

Paul Bernardo.

- Williams, Stephen (2004). Karla: A Pact with the Devil. Seal Books. ISBN 0-7704-2962-9.

- Pron, Nick (August 14, 2012). Lethal Marriage: The Uncensored Truth Behind the Crimes of Paul Bernardo and Karla Homolka. Doubleday Canada. ISBN 978-0-385-67417-1.

External links

[edit]- Fowles, Stacey May (December 2013). "Boy Next Door". The Walrus. 10 (10). Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- 1964 births

- 1988 murders in Canada

- 1989 murders in Canada

- 1990 murders in Canada

- 1991 murders in Canada

- 1992 murders in Canada

- 20th-century Canadian criminals

- Canadian kidnappers

- Canadian male criminals

- Canadian murderers of children

- Canadian people convicted of murder

- Canadian prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- Canadian rapists

- Canadian serial killers

- Crime in Toronto

- Criminals from Ontario

- Criminal couples

- Serial killer duos

- Fugitives

- Living people

- People convicted of murder by Canada

- People from Scarborough, Ontario

- People from St. Catharines

- People with sexual sadism disorder

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by Canada

- Publication bans in Canadian case law

- Rape in the 1980s

- Rape in the 1990s

- Torture in Canada

- University of Toronto alumni

- Violence against women in Canada