Singapore

Republic of Singapore | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Majulah Singapura (Malay) "Onward Singapore" | |

| Anthem: Majulah Singapura (Malay) "Onward Singapore" | |

| |

| Capital | Singapore (city-state)[a] 1°17′N 103°50′E / 1.283°N 103.833°E |

| Largest planning area by population | Bedok[1] |

| Official languages | |

| National language | Malay |

| Ethnic groups (2023)[b] | |

| Religion (2020)[c] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Singaporean |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Tharman Shanmugaratnam | |

| Lawrence Wong | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Independence from the United Kingdom and Malaysia | |

| 3 June 1959 | |

| 16 September 1963 | |

| 9 August 1965 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 735.6 km2 (284.0 sq mi)[4] (176th) |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• Density | 7,804/km2 (20,212.3/sq mi) (2nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2023) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | very high (9th) |

| Currency | Singapore dollar (S$) (SGD) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (Singapore Standard Time) |

| Calling code | +65 |

| ISO 3166 code | SG |

| Internet TLD | .sg |

Singapore,[e] officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree of latitude (137 kilometres or 85 miles) north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bordering the Strait of Malacca to the west, the Singapore Strait to the south along with the Riau Islands in Indonesia, the South China Sea to the east, and the Straits of Johor along with the State of Johor in Malaysia to the north.

Singapore's history dates back at least eight hundred years, having been a maritime emporium known as Temasek and subsequently a major constituent part of several successive thalassocratic empires. Its contemporary era began in 1819, when Stamford Raffles established Singapore as an entrepôt trading post of the British Empire. In 1867, Singapore came under the direct control of Britain as part of the Straits Settlements. During World War II, Singapore was occupied by Japan in 1942 and returned to British control as a separate Crown colony following Japan's surrender in 1945. Singapore gained self-governance in 1959 and, in 1963, became part of the new federation of Malaysia, alongside Malaya, North Borneo, and Sarawak. Ideological differences led to Singapore's expulsion from the federation two years later; Singapore became an independent sovereign country in 1965. After early years of turbulence and despite lacking natural resources and a hinterland, the nation rapidly developed to become one of the Four Asian Tigers.

As a highly developed country, it has one of the highest GDP per capita (PPP) in the world. It is also identified as a tax haven. Singapore is the only country in Asia with a AAA sovereign credit rating from all major rating agencies. It is a major aviation, financial, and maritime shipping hub and has consistently been ranked as one of the most expensive cities to live in for expatriates and foreign workers. Singapore ranks highly in key social indicators: education, healthcare, quality of life, personal safety, infrastructure, and housing, with a home-ownership rate of 88 percent. Singaporeans enjoy one of the longest life expectancies, fastest Internet connection speeds, lowest infant mortality rates, and lowest levels of corruption in the world. It has the third highest population density of any country in the world, although there are numerous green and recreational spaces as a result of urban planning. With a multicultural population and in recognition of the cultural identities of the major ethnic groups within the nation, Singapore has four official languages: English, Malay, Mandarin, and Tamil. English is the common language, with exclusive use in numerous public services. Multi-racialism is enshrined in the constitution and continues to shape national policies in education, housing, and politics.

Singapore is a parliamentary republic in the Westminster tradition of unicameral parliamentary government, and its legal system is based on common law. While the country is de jure a multi-party democracy with free elections, the government under the People's Action Party (PAP) wields widespread control and political dominance. The PAP has governed the country continuously since full internal self-government was achieved in 1959, and holds a supermajority in Parliament. One of the five founding members of ASEAN, Singapore is also the headquarters of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Secretariat, the Pacific Economic Cooperation Council Secretariat, and is the host city of many international conferences and events. Singapore is also a member of the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, the East Asia Summit, the Non-Aligned Movement, and the Commonwealth of Nations.

Name and etymology

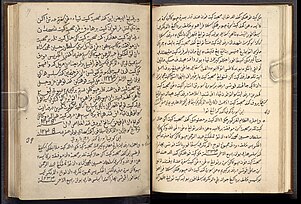

The English name of "Singapore" is an anglicisation of the native Malay name for the country, Singapura (pronounced [siŋapura]), which was in turn derived from the Sanskrit word for 'lion city' (Sanskrit: सिंहपुर; romanised: Siṃhapura; Brahmi: 𑀲𑀺𑀁𑀳𑀧𑀼𑀭; literally "lion city"; siṃha means 'lion', pura means 'city' or 'fortress').[9] Pulau Ujong was one of the earliest references to Singapore Island, which corresponds to a Chinese account from the third century referred to a place as Pú Luó Zhōng (Chinese: 蒲 羅 中), a transcription of the Malay name for 'island at the end of a peninsula'.[10] Early references to the name Temasek (or Tumasik) are found in the Nagarakretagama, a Javanese eulogy written in 1365, and a Vietnamese source from the same time period. The name possibly means Sea Town, being derived from the Malay tasek, meaning 'sea' or 'lake'.[11] The Chinese traveller Wang Dayuan visited a place around 1330 named Danmaxi (Chinese: 淡馬錫; pinyin: Dànmǎxí; Wade–Giles: Tan Ma Hsi) or Tam ma siak, depending on pronunciation; this may be a transcription of Temasek, alternatively, it may be a combination of the Malay Tanah meaning 'land' and Chinese xi meaning 'tin', which was traded on the island.[12][11]

Variations of the name Siṃhapura were used for a number of cities throughout the region prior to the establishment of the Kingdom of Singapura. In Hindu–Buddhist culture, lions were associated with power and protection, which may explain the attraction of such a name.[13][14] The name Singapura supplanted Temasek sometime before the 15th century, after the establishment of the Kingdom of Singapura on the island by a fleeing Sumatran Raja (prince) from Palembang. However, the precise time and reason for the name change is unknown. The semi-historical Malay Annals state that Temasek was christened Singapura by Sang Nila Utama, a 13th-century Sumatran Raja from Palembang. The Annals state that Sang Nila Utama encountered a strange beast on the island that he took to be a lion. Seeing this as an omen, he established the town of Singapura where he encountered the beast.[15]: 37, 88–92 [16]: 30–31 The second hypothesis, drawn from Portuguese sources, postulates that this mythical story is based on the real life Parameswara of Palembang. Parameswara declared independence from Majapahit and mounted a Lion Throne. After then being driven into exile by the Javanese, he usurped control over Temasek. He may have rechristened the area as Singapura, recalling the throne he had been driven from.[17]

Under Japanese occupation, Singapore was renamed Syonan-to (Japanese: 昭 南, Hepburn: Shōnan), meaning 'light of the south'.[18][19] Singapore is sometimes referred to by the nickname the "Garden City", in reference to its parks and tree-lined streets.[20] Another informal name, the "Little Red Dot", was adopted after an article in the Asian Wall Street Journal of 4 August 1998 said that Indonesian President B. J. Habibie referred to Singapore as a red dot on a map.[21][22][23][24]

History

Ancient Singapore

In 1299, according to the Malay Annals, the Kingdom of Singapura was founded on the island by Sang Nila Utama.[25] Although the historicity of the accounts as given in the Malay Annals is the subject of academic debates,[26] it is nevertheless known from various documents that Singapore in the 14th century, then known as Temasek, was a trading port under the influence of both the Majapahit Empire and the Siamese kingdoms,[27] and was a part of the Indosphere.[28][29][30][31][32] These Indianised kingdoms were characterised by surprising resilience, political integrity and administrative stability.[33] Historical sources also indicate that around the end of the 14th century, its ruler Parameswara was attacked by either the Majapahit or the Siamese, forcing him to move to Malacca where he founded the Sultanate of Malacca.[34] Archaeological evidence suggests that the main settlement on Fort Canning Hill was abandoned around this time, although a small trading settlement continued in Singapore for some time afterwards.[17] In 1613, Portuguese raiders burned down the settlement, and the island faded into obscurity for the next two centuries.[35] By then, Singapore was nominally part of the Johor Sultanate.[36] The wider maritime region and much trade was under Dutch control for the following period after the 1641 Dutch conquest of Malacca.[37]

British colonisation

The British governor Stamford Raffles arrived in Singapore on 28 January 1819 and soon recognised the island as a natural choice for the new port.[40] The island was then nominally ruled by Tengku Abdul Rahman, the Sultan of Johor, who was controlled by the Dutch and the Bugis.[41] However, the Sultanate was weakened by factional division: Abdul Rahman, the Temenggong of Johor to Tengku Abdul Rahman, as well as his officials, were loyal to the Sultan's elder brother Tengku Long, who was living in exile in Penyengat Island, Riau Islands. With the Temenggong's help, Raffles managed to smuggle Tengku Long back into Singapore. Raffles offered to recognise Tengku Long as the rightful Sultan of Johor, under the title of Sultan Hussein, as well as provide him with a yearly payment of $5000 and another $3000 to the Temenggong; in return, Sultan Hussein would grant the British the right to establish a trading post on Singapore.[42] The Treaty of Singapore was signed on 6 February 1819.[43][44]

In 1824, a further treaty with the Sultan led to the entire island becoming a part of the British Empire.[45] In 1826, Singapore became part of the Straits Settlements, then under the jurisdiction of British India. Singapore became the regional capital in 1836.[46] Prior to Raffles' arrival, there were only about a thousand people living on the island, mostly indigenous Malays along with a handful of Chinese.[47] By 1860 the population had swelled to over 80,000, more than half being Chinese.[45] Many of these early immigrants came to work on the pepper and gambier plantations.[48] In 1867, the Straits Settlements were separated from British India, coming under the direct control of Britain.[49] Later, in the 1890s, when the rubber industry became established in Malaya and Singapore,[50] the island became a global centre for rubber sorting and export.[45]

Singapore was not greatly affected by the First World War (1914–18), as the conflict did not spread to Southeast Asia. The only significant event during the war was the 1915 Singapore Mutiny by Muslim sepoys from British India, who were garrisoned in Singapore.[51] After hearing rumours that they were to be sent to fight the Ottoman Empire, a Muslim state, the soldiers rebelled, killing their officers and several British civilians before the mutiny was suppressed by non-Muslim troops arriving from Johore and Burma.[52]

After World War I, the British built the large Singapore Naval Base as part of the defensive Singapore strategy.[53] Originally announced in 1921, the construction of the base proceeded at a slow pace until the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931. Costing $60 million and not fully completed in 1938, it was nonetheless the largest dry dock in the world, the third-largest floating dock, and had enough fuel tanks to support the entire British navy for six months.[53][54][55] The base was defended by heavy 15-inch (380 mm) naval guns stationed at Fort Siloso, Fort Canning and Labrador, as well as a Royal Air Force airfield at Tengah Air Base. Winston Churchill touted it as the "Gibraltar of the East", and military discussions often referred to the base as simply "East of Suez". However, the British Home Fleet was stationed in Europe, and the British could not afford to build a second fleet to protect their interests in Asia. The plan was for the Home Fleet to sail quickly to Singapore in the event of an emergency. As a consequence, after World War II broke out in 1939, the fleet was fully occupied with defending Britain, leaving Singapore vulnerable to Japanese invasion.[56][57]

Japanese occupation

During the Pacific War, the Japanese invasion of Malaya culminated in the Battle of Singapore. When the British force of 60,000 troops surrendered on 15 February 1942, British prime minister Winston Churchill called the defeat "the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history".[58] British and Empire losses during the fighting for Singapore were heavy, with a total of nearly 85,000 personnel captured.[59] About 5,000 were killed or wounded,[60] of which Australians made up the majority.[61][62][63] Japanese casualties during the fighting in Singapore amounted to 1,714 killed and 3,378 wounded.[59][f] The occupation was to become a major turning point in the histories of several nations, including those of Japan, Britain, and Singapore. Japanese newspapers triumphantly declared the victory as deciding the general situation of the war.[64][65] Between 5,000 and 25,000 ethnic Chinese people were killed in the subsequent Sook Ching massacre.[66] British forces had planned to liberate Singapore in 1945/1946; however, the war ended before these operations could be carried out.[67][68]

Post-war period

After the Japanese surrender to the Allies on 15 August 1945, Singapore fell into a brief state of violence and disorder; looting and revenge-killing were widespread. British, Australian, and Indian troops led by Lord Louis Mountbatten returned to Singapore to receive the formal surrender of Japanese forces in the region from General Seishirō Itagaki on behalf of General Hisaichi Terauchi on 12 September 1945.[67][68] Meanwhile, Tomoyuki Yamashita was tried by a US military commission for war crimes, but not for crimes committed by his troops in Malaya or Singapore. He was convicted and hanged in the Philippines on 23 February 1946.[69][70]

Much of the infrastructure in Singapore had been destroyed during the war, including those needed to supply utilities. A shortage of food led to malnutrition, disease, and rampant crime and violence. A series of strikes in 1947 caused massive stoppages in public transport and other services. However, by late 1947 the economy began to recover, facilitated by a growing international demand for tin and rubber.[71] The failure of Britain to successfully defend its colony against the Japanese changed its image in the eyes of Singaporeans. British Military Administration ended on 1 April 1946, and Singapore became a separate Crown Colony.[71] In July 1947, separate Executive and Legislative Councils were established and the election of six members of the Legislative Council was scheduled for the following year.[72]

During the 1950s, Chinese communists, with strong ties to the trade unions and Chinese schools, waged a guerrilla war against the government, leading to the Malayan Emergency. The 1954 National Service riots, Hock Lee bus riots, and Chinese middle schools riots in Singapore were all linked to these events.[73] David Marshall, pro-independence leader of the Labour Front, won Singapore's first general election in 1955.[74] He led a delegation to London, and Britain rejected his demand for complete self-rule. He resigned and was replaced by Lim Yew Hock in 1956, and after further negotiations Britain agreed to grant Singapore full internal self-government for all matters except defence and foreign affairs on 3 June 1959.[75] Days before, in the 30 May 1959 election, the People's Action Party (PAP) won a landslide victory.[76] Governor Sir William Allmond Codrington Goode served as the first Yang di-Pertuan Negara (Head of State).[77]

Within Malaysia

PAP leaders believed that Singapore's future lay with Malaya, due to strong ties between the two. It was thought that reuniting with Malaya would benefit the economy by creating a common market, alleviating ongoing unemployment woes in Singapore. However, a sizeable left-wing faction of the PAP was strongly opposed to the merger, fearing a loss of influence, and hence formed the Barisan Sosialis, after being kicked out from the PAP.[78][79] The ruling party of Malaya, United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), was staunchly anti-communist, and it was suspected UMNO would support the non-communist factions of PAP. UMNO, initially sceptical of the idea of a merger due to distrust of the PAP government and concern that the large ethnic Chinese population in Singapore would alter the racial balance in Malaya on which their political power base depended, became supportive of the idea of the merger due to joint fear of a communist takeover.[80]

On 27 May 1961, Malaya's prime minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, made a surprise proposal for a new Federation called Malaysia, which would unite the current and former British possessions in the region: the Federation of Malaya, Singapore, Brunei, North Borneo, and Sarawak.[80][81] UMNO leaders believed that the additional Malay population in the Bornean territories would balance Singapore's Chinese population.[75] The British government, for its part, believed that the merger would prevent Singapore from becoming a haven for communism.[82] To obtain a mandate for a merger, the PAP held a referendum on the merger. This referendum included a choice of different terms for a merger with Malaysia and had no option for avoiding merger altogether.[83][84] On 16 September 1963, Singapore joined with Malaya, the North Borneo, and Sarawak to form the new Federation of Malaysia under the terms of the Malaysia Agreement.[85] Under this Agreement, Singapore had a relatively high level of autonomy compared to the other states of Malaysia.[86]

Indonesia opposed the formation of Malaysia due to its own claims over Borneo and launched Konfrontasi ("Confrontation" in Indonesian) in response to the formation of Malaysia.[87] On 10 March 1965, a bomb planted by Indonesian saboteurs on a mezzanine floor of MacDonald House exploded, killing three people and injuring 33 others. It was the deadliest of at least 42 bomb incidents which occurred during the confrontation.[88] Two members of the Indonesian Marine Corps, Osman bin Haji Mohamed Ali and Harun bin Said, were eventually convicted and executed for the crime.[89] The explosion caused US$250,000 (equivalent to US$2,417,107 in 2023) in damages to MacDonald House.[90][91]

Even after the merger, the Singaporean government and the Malaysian central government disagreed on many political and economic issues.[92] Despite an agreement to establish a common market, Singapore continued to face restrictions when trading with the rest of Malaysia. In retaliation, Singapore did not extend to Sabah and Sarawak the full extent of the loans agreed to for economic development of the two eastern states. Talks soon broke down, and abusive speeches and writing became rife on both sides. This led to communal strife in Singapore, culminating in the 1964 race riots.[93] On 7 August 1965, Malaysian prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman, seeing no alternative to avoid further bloodshed (and with the help of secret negotiations by PAP leaders, as revealed in 2015)[94] advised the Parliament of Malaysia that it should vote to expel Singapore from Malaysia.[92] On 9 August 1965, the Malaysian Parliament voted 126 to 0 to move a bill to amend the constitution, expelling Singapore from Malaysia, which left Singapore as a newly independent country.[75][95][96][97][98][94]

Republic of Singapore

After being expelled from Malaysia, Singapore became independent as the Republic of Singapore on 9 August 1965,[99][100] with Lee Kuan Yew and Yusof bin Ishak as the first prime minister and president respectively.[101][102] In 1967, the country co-founded the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).[103] Race riots broke out once more in 1969.[104] Lee Kuan Yew's emphasis on rapid economic growth, support for business entrepreneurship, and limitations on internal democracy shaped Singapore's policies for the next half-century.[105][106] Economic growth continued throughout the 1980s, with the unemployment rate falling to 3% and real GDP growth averaging at about 8% up until 1999. During the 1980s, Singapore began to shift towards high-tech industries, such as the wafer fabrication sector, in order to remain competitive as neighbouring countries began manufacturing with cheaper labour. Singapore Changi Airport was opened in 1981 and Singapore Airlines was formed.[107] The Port of Singapore became one of the world's busiest ports and the service and tourism industries also grew immensely during this period.[108][109]

The PAP has remained in power since independence. Some activists and opposition politicians see the government's strict regulation of political and media activities as an infringement on political rights.[110] In response, Singapore has seen several significant political changes, such as the introduction of the non-constituency members of parliament in 1984 to allow up to three losing candidates from opposition parties to be appointed as MPs. Group representation constituencies (GRCs) were introduced in 1988 to create multi-seat electoral divisions, intended to ensure minority representation in parliament.[111] Nominated members of parliament were introduced in 1990 to allow non-elected non-partisan MPs.[112] The constitution was amended in 1991 to provide for an elected president who has veto power in the use of past reserves and appointments to certain public offices.[113]

In 1990, Goh Chok Tong succeeded Lee and became Singapore's second prime minister.[114] During Goh's tenure, the country went through the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the 2003 SARS outbreak.[115][116] In 2004, Lee Hsien Loong, the eldest son of Lee Kuan Yew, became the country's third prime minister.[116] Lee Hsien Loong's tenure included the 2007–2008 financial crisis, the resolution of a dispute over land ownership at Tanjong Pagar railway station between Singapore and Malaysia, the introduction of the two integrated resorts (IRs), located at the Marina Bay Sands and Resorts World Sentosa, and the COVID-19 pandemic.[117] The PAP suffered its worst ever electoral results in 2011, winning just 60% of votes, amidst debate over issues including the influx of foreign workers and the high cost of living.[118] On 23 March 2015, Lee Kuan Yew died, and a one-week period of public mourning was observed nationwide.[106] Subsequently, the PAP regained its dominance in Parliament through the September general election, receiving 69.9% of the popular vote,[119] although this remained lower than the 2001 tally of 75.3%[120] and the 1968 tally of 86.7%.[121] The 2020 election held in July saw the PAP drop to 61% of the vote, while the Workers' Party took 10 of the 93 seats, the highest number ever won by another party.[122] On 15 May 2024, Lawrence Wong became Singapore's fourth Prime Minister; he is the first prime minister born after independence.[123]

Government and politics

Singapore is a parliamentary republic based on the Westminster system. The Constitution of Singapore is the supreme law of the country, establishing the structure and responsibility of governance. The President is the head of state.[124][125] The governance of Singapore is separated into three branches:

- Executive: The executive consists of the cabinet, led by the prime minister, and the Attorney General's Chambers led by the Attorney-General.[126] The cabinet is collectively responsible for all government policies and the day-to-day administration of the affairs of state. It is typically composed of members of the Singapore Parliament. The prime minister is appointed by the President, and the ministers in the cabinet and the attorney-general are appointed by the president, acting on the advice and consent of the prime minister. The prime minister is the effective head of the executive branch of government.[127][124]

- Legislature: The Singapore Parliament is unicameral and, together with the president, comprises the legislature.[128] Members of Parliament (MP) consist of elected, non-constituency, and nominated members. The majority of MPs are elected into parliament at a general election. The Singapore Parliament is collectively responsible for enacting the laws governing the state.[124] The president holds limited discretionary powers of oversight over the government. The president's veto powers are further subject to parliamentary overruling.[129][130]

- Judiciary: The judiciary's function is to independently administer justice and is headed by the Chief Justice. The judges and judicial commissioners are appointed by the president on the advice of the prime minister.[131] The Supreme Court and State Courts adjudicates in civil disputes between persons, convicts or acquits accused persons in criminal prosecutions, and interprets laws to decide on its constitutionality. Any law or provision of a law found to be unconstitutional can be struck down by the Supreme Court.[132]

The president is directly elected by popular vote for a renewable six-year term. Requirements for this position, which were enacted by the PAP government, are extremely stringent, such that only a handful of people qualify for the candidacy.[133][134] These qualifications include that a candidate needs to be a person at least 45 years of age who is no longer a member of a political party, to either have held public office for at least 3 years in a number of specific public service leadership roles, or to have 3 years experience as chief executive of a fully profitable private sector company with at least S$500 million in shareholders' equity, be a resident in Singapore for at least 10 years, not have a criminal record, and more.[135][134][136] Candidates must also "satisfy" the Presidential Elections Committee (PEC) that he or she is a person of integrity, good character and reputation.[citation needed]

From 2017, the Constitution requires that presidential elections be "reserved" for a racial community if no one from that ethnic group has been elected to the presidency in the five most recent terms.[137] Only members of that community may qualify as candidates in a reserved presidential election.[138] In the 2017 presidential election, this combination of stringent requirements and a reserved election that required the candidate to be of the 13% Malay ethnic group led to the PEC approving a single candidate for the presidency;[139] Halimah Yacob, considered part of the Malay community, won in an uncontested election. She also became Singapore's first female president.

Members of Parliament (MPs) are elected at least every five years (or sooner with a snap election). The 14th and current Parliament has 103 members; 93 were directly elected from the 31 constituencies, nine are nonpartisan nominated members appointed by the president, and three are non-constituency members from opposition parties who were not elected in the last general election but appointed to the legislature to increase opposition party representation. In group representation constituencies (GRCs), political parties assemble teams of candidates to contest elections. At least one MP in a GRC must be of an ethnic minority background. All elections are held using first-past-the-post voting.[140] MPs host weekly political surgeries, called "Meet-the-People Sessions", where they help constituents resolve personal issues which can be related to housing, financial assistance, and immigration.[141]

The People's Action Party occupies a dominant position in Singaporean politics, having won large parliamentary majorities in every election since self-governance was granted in 1959. The PAP, self-described as pragmatic, have a syncretic ideology combining free-market principles, civil nationalism, and welfarism.[142][143][144] Despite promulgating restrictions on civil liberties, Singapore under the PAP has seen consistent economic growth and political stability.[145] The most represented and popular opposition party is the centre-left Workers' Party, which holds 8 seats in Parliament.[122]

The long-standing hegemony of the People's Action Party has led to Singapore being described by academics as an illiberal democracy,[146][147][148][149] or a soft-authoritarian state in which the PAP faces little to no feasible political competition to its rule of the country.[150][151][152][153] The multi-party democratic process of Singapore has been described as "minimal" in comparison to the state's focus on economic development and social order.[154] According to Gordon P. Means, professor emeritus of political science at McMaster University, Singapore reinvented the "benevolent" yet "highly authoritarian" colonial system of governance inherited from Britain rather than forging a full democracy. A conservative ideology of "Asian values" evolved to replace British rule, based on "communal loyalty, distrust of government, and avoidance of individual or collective responsibility for wider public interests", with less regard for human rights in the nascent Western sense.[155] The fact that "neither the public nor elites had experience with democracy" helped create Singapore's political culture, as dominated by status-focused hierarchies committed to economic development.[151] The legacy of Asian values and the limited political culture within Singapore has led to the country being described as "classic illustration of soft authoritarianism",[154] and "profoundly illiberal".[156]

The judicial system is based on English common law, continuing the legal tradition established during British rule and with substantial local differences. Criminal law is based on the Indian Penal Code originally intended for British India, and was at the time as a crown colony also adopted by the British colonial authorities in Singapore and remains the basis of the criminal code in the country with a few exceptions, amendments and repeals since it came into force.[157] Trial by jury was abolished in 1970.[158] Singapore is known for its strict laws and conservative stances on crime; both corporal punishment (by caning)[159][160] and capital punishment (by hanging) are retained and commonly used as legal penalties.[161]

The right to freedom of speech and association is guaranteed by Article 14(1) of the Constitution of Singapore, although there are provisions in the subsequent subsection that regulate them.[162] The government has restricted freedom of speech and freedom of the press as well as some civil and political rights.[163] In 2023, Singapore was ranked 129th out of 180 nations by Reporters Without Borders on the global Press Freedom Index.[164] Freedom House ranks Singapore as "partly free" in its Freedom in the World report,[165][145] and the Economist Intelligence Unit ranks Singapore as a "flawed democracy", the second freest rank of four, in its "Democracy Index".[166][167] All public gatherings of five or more people require police permits, and protests may legally be held only at the Speakers' Corner.[168]

In the Corruption Perceptions Index, which ranks countries by "perceived levels of public sector corruption", Singapore has consistently ranked as one of the least corrupt countries in the world, in spite of being illiberal.[169] Singapore's unique combination of a strong, soft authoritarian government with an emphasis on meritocracy is known as the "Singapore model", and is regarded as a key factor behind Singapore's political stability, economic growth, and harmonious social order.[170][171][172][173] In 2021, the World Justice Project's Rule of Law Index ranked Singapore as 17th overall among the world's 193 countries for adherence to the rule of law. Singapore ranked high on the factors of order and security (#3), absence of corruption (#3), regulatory enforcement (#4), civil justice (#8), and criminal justice (#7), and ranked significantly lower on factors of open government (#34), constraints on government powers (#32), and fundamental rights (#38).[174]

Foreign relations

Singapore's stated foreign policy priority is maintaining security in Southeast Asia and surrounding territories. An underlying principle is political and economic stability in the region.[175] It has diplomatic relations with more than 180 sovereign states.[176]

As one of the five founding members of ASEAN,[177] Singapore is a strong supporter of the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) and the ASEAN Investment Area (AIA); it is also the host of the APEC Secretariat.[178] Singapore is also a founding member of The Forum of Small States (FOSS), a voluntary and informal grouping at the UN.[179]

Singapore maintains membership in other regional organisations, such as Asia–Europe Meeting, the Forum for East Asia-Latin American Cooperation, the Indian Ocean Rim Association, and the East Asia Summit.[175] It is also a member of the Non-Aligned Movement,[180] the United Nations and the Commonwealth.[181][182] While Singapore is not a formal member of the G20, it has been invited to participate in G20 processes in most years since 2010.[183] Singapore is also the location of the Pacific Economic Cooperation Council (PECC) Secretariat.[184]

In general, bilateral relations with other ASEAN members are strong; however, disagreements have arisen,[185] and relations with neighbouring Malaysia and Indonesia have sometimes been strained.[186] Malaysia and Singapore have clashed over the delivery of fresh water to Singapore,[187] and access by the Singapore Armed Forces to Malaysian airspace.[186] Border issues exist with Malaysia and Indonesia, and both have banned the sale of marine sand to Singapore over disputes about Singapore's land reclamation.[188] Some previous disputes, such as the Pedra Branca dispute, have been resolved by the International Court of Justice.[189] Piracy in the Strait of Malacca has been a cause of concern for all three countries.[187] Close economic ties exist with Brunei, and the two share a pegged currency value, through a Currency Interchangeability Agreement between the two countries which makes both Brunei dollar and Singapore dollar banknotes and coins legal tender in either country.[190][191]

The first diplomatic contact with China was made in the 1970s, with full diplomatic relations established in the 1990s. China has been Singapore's largest trading partner since 2013, after surpassing Malaysia.[192][193][194][195][196] Singapore and the United States share a long-standing close relationship, in particular in defence, the economy, health, and education. Singapore has also increased co-operation with ASEAN members and China to strengthen regional security and fight terrorism, and participated in ASEAN's first joint maritime exercise with China in 2018.[197] It has also given support to the US-led coalition to fight terrorism, with bilateral co-operation in counter-terrorism and counter-proliferation initiatives, and joint military exercises.[185]

As Singapore has diplomatic relations with both the United States and North Korea, and was one of the few countries that have relationships with both countries,[198] in June 2018, it hosted a historic summit between US President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, the first-ever meeting between the sitting leaders of the two nations.[199][200] It also hosted the Ma–Xi meeting in 2015, the first meeting between the political leaders of the two sides of the Taiwan Strait since the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1950.[201][202][203]

Military

The Singaporean military, arguably the most technologically advanced in Southeast Asia,[204] consists of the Army, the Navy, the Air Force and the Digital and Intelligence Service. It is seen as the guarantor of the country's independence,[205] translating into Singapore culture, involving all citizens in the country's defence.[206] The government spent 2.7% of the country's GDP on the military in 2024, the highest in the region.[207]

After its independence, Singapore had only two infantry regiments commanded by British officers. Considered too small to provide effective security for the new country, the development of its military forces became a priority.[208] In addition, in October 1971, Britain pulled its military out of Singapore, leaving behind only a small British, Australian and New Zealand force as a token military presence.[209] A great deal of initial support came from Israel,[208] a country unrecognised by Singapore's neighbouring Muslim-majority nations of Malaysia and Indonesia.[210][211][212] The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) commanders were tasked by the Singapore Government to create the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) from scratch, and Israeli instructors were brought in to train Singaporean soldiers. Military courses were conducted according to the IDF's format, and Singapore adopted a system of conscription and reserve service based on the Israeli model.[208] Singapore still maintains strong security ties with Israel and is one of the biggest buyers of Israeli arms and weapons systems,[213] with one recent example being the MATADOR anti-tank weapon.[214]

The SAF is being developed to respond to a wide range of issues in both conventional and unconventional warfare. The Defence Science and Technology Agency (DSTA) is responsible for procuring resources for the military.[215] The geographic restrictions of Singapore mean that the SAF must plan to fully repulse an attack, as they cannot fall back and re-group. The small size of the population has also affected the way the SAF has been designed, with a small active force and a large number of reserves.[206]

Singapore has conscription for all able-bodied males at age 18, except those with a criminal record or who can prove that their loss would bring hardship to their families. Males who have yet to complete pre-university education, are awarded the Public Service Commission (PSC) scholarship, or are pursuing a local medical degree can opt to defer their draft.[216][217] Though not required to perform military service, the number of women in the SAF has been increasing: since 1989 they have been allowed to fill military vocations formerly reserved for men. Before induction into a specific branch of the armed forces, recruits undergo at least nine weeks of basic military training.[218]

Because of the scarcity of open land on the main island, training involving activities such as live firing and amphibious warfare are often carried out on smaller islands, typically barred to civilian access. However, large-scale drills, considered too dangerous to be performed in the country, have been performed in other countries such as Brunei, Indonesia, Thailand and the United States. In general, military exercises are held with foreign forces once or twice per week.[206] Due to airspace and land constraints, the Republic of Singapore Air Force (RSAF) maintains a number of overseas bases in Australia, the United States, and France. The RSAF's 130 Squadron is based in RAAF Base Pearce, Western Australia,[219] and its 126 Squadron is based in the Oakey Army Aviation Centre, Queensland.[220] The RSAF has one squadron—the 150 Squadron—based in Cazaux Air Base in southern France.[221] The RSAF's overseas detachments in the United States are: Luke Air Force Base in Arizona, Marana in Arizona, Mountain Home Air Force Base in Idaho, and Andersen Air Force Base in Guam.[222][223][224]

The SAF has sent forces to assist in operations outside the country, in areas such as Iraq,[225] and Afghanistan,[226][227] in both military and civilian roles. In the region, they have helped to stabilise East Timor and have provided aid to Aceh in Indonesia following the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami.[citation needed] Since 2009, the Republic of Singapore Navy (RSN) has deployed ships to the Gulf of Aden to aid in countering piracy efforts as part of Task Force 151.[228] The SAF also helped in relief efforts during Hurricane Katrina,[229] and Typhoon Haiyan.[230] Singapore is part of the Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA), a military alliance with Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.[206] According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Singapore is the 5th most peaceful country in the world.[231]

Human rights

Capital punishment is a legal and enforced penalty in Singapore. The country is one of four in the developed world to retain the death penalty, along with the United States, Japan and Taiwan. Particularly, its use against drug trafficking has been a source of contention with various non-governmental organisations,[who?] regarded by some as a victimless crime.[citation needed] The government has responded that it has "no doubts" that it is the right policy and that there is "clear evidence" of serious deterrence, and that the law should be looked at upon in the wider context of "saving lives", particularly citizens.[232] In 2004, Amnesty International claimed that some legal provisions of the Singapore system for the death penalty conflict with "the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty".[233] The government has disputed Amnesty's claims, stating that their "position on abolition of the death penalty is by no means uncontested internationally" and that the report contains "grave errors of facts and misrepresentations".[234]

From 1938 to 2023, sexual relations between men were technically illegal under Section 377A of the Penal Code, first introduced during British colonial rule.[235] During the last few decades, this law was mostly unenforced and pressure to repeal it increased as homosexuality became more accepted by Singaporean society.[236] Meanwhile, sexual relations between women had always been legal.[237] In 2022, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced that Singapore would repeal 377A, effectively decriminalising homosexual behaviour. Nevertheless, he added that the repeal will not affect the recognition of "traditional familial and societal norms," including how marriage is defined, leaving the legal status of same-sex marriage unchanged for the time, although the possibility of civil unions was not officially ruled out.[238] Lee described this as a compromise between the conservative (and often religious) and progressive elements of Singaporean society to prevent further political fracturing.[239] The law was officially repealed on 3 January 2023.[240]

Pink Dot SG, an event held in support of the LGBT community, has drawn thousands of people annually since 2009 with increasing attendance.[241] According to a survey conducted by the Institute of Policy Studies in 2019, Singaporean society has become more liberal on LGBT rights. In the survey, more than 20% of people said that sexual relations between adults of the same sex were not wrong at all or not wrong most of the time, up from 10% in 2013. The survey found that 27% felt the same way about same-sex marriage (an increase from 15% in 2013) and 30% did so about same-sex couples adopting a child (an increase from 24% in 2013).[242][243] In 2021, six Singaporeans protested for improved trans protections in the educational system outside the Ministry of Education headquarters at Buona Vista.[244]

Pimps often traffic women from neighbouring countries such as China, Malaysia and Vietnam at their brothels as well as rented apartments and hostels for higher profit margins when they get a cut from customers.[245][246] In response, amendments were made to the Women's Charter by the government in 2019 to legislate more serious punishments for traffickers, including imprisonment of up to seven years and a fine of S$100,000.[247]

Economy

Singapore has a highly developed market economy, based historically on extended entrepôt trade. Along with Hong Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan, Singapore is one of the Four Asian Tigers, and has surpassed its peers in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita. Between 1965 and 1995, growth rates averaged around 6 per cent per annum, transforming the living standards of the population.[248]

The Singaporean economy is regarded as free,[249] innovative,[250] dynamic[251] and business-friendly.[252] For several years, Singapore has been one of the few[253] countries with a AAA credit rating from the big three, and the only Asian country to achieve this rating.[254] Singapore attracts a large amount of foreign investment as a result of its location, skilled workforce, low tax rates, advanced infrastructure and zero-tolerance against corruption.[255] It was the world's 4th most competitive economy in 2023, according to the International Institute for Management Development's World Competitiveness Ranking of 64 countries,[256] with the highest GDP (PPP) per capita.[257][258][259] Roughly 44 percent of the Singaporean workforce is made up of non-Singaporeans.[260] Despite market freedom, Singapore's government operations have a significant stake in the economy, contributing 22% of the GDP.[261] The city is a popular location for conferences and events.[262]

The currency of Singapore is the Singapore dollar (SGD or S$), issued by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS).[263] It has been interchangeable with the Brunei dollar at par value since 1967.[264] MAS manages its monetary policy by allowing the Singapore dollar exchange rate to rise or fall within an undisclosed trading band. This is different from most central banks, which use interest rates to manage policy.[265] Singapore has the world's eleventh largest foreign reserves,[266] and one of the highest net international investment position per capita.[267][268]

Singapore has been identified as a tax haven[269] for the wealthy due to its low tax rates on personal income and tax exemptions on foreign-based income and capital gains. Individuals such as Australian millionaire retailer Brett Blundy and multi-billionaire Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin are two examples of wealthy individuals who have settled in Singapore.[270] In 2009, Singapore was removed from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) "liste grise" of tax havens,[271] and ranked fourth on the Tax Justice Network's 2015 Financial Secrecy Index of the world's off-shore financial service providers, banking one-eighth of the world's offshore capital, while "providing numerous tax avoidance and evasion opportunities".[272] In August 2016, The Straits Times reported that Indonesia had decided to create tax havens on two islands near Singapore to bring Indonesian capital back into the tax base.[273] In October 2016, the Monetary Authority of Singapore admonished and fined UBS and DBS and withdrew Falcon Private Bank's banking licence for their alleged role in the Malaysian Sovereign Fund scandal.[274][275]

In 2016, Singapore was rated the world's most expensive city for the third consecutive year by the Economist Intelligence Unit,[276][277] and this remained true in 2018.[278] The government provides numerous assistance programmes to the homeless and needy through the Ministry of Social and Family Development, so acute poverty is rare. Some of the programmes include providing financial assistance to needy households, providing free medical care at government hospitals, and paying for children's tuition.[279][280][281] Other benefits include compensation for gym fees to encourage citizens to exercise,[282] up to S$166,000 as a baby bonus for each citizen,[283] heavily subsidised healthcare, financial aid for the disabled, the provision of reduced-cost laptops for poor students,[284] rebates for costs such as public transport[285] and utility bills, and more.[286][287] As of 2018 Singapore's ranking in the Human Development Index is 9th in the world, with an HDI value of 0.935.[288]

Geography

Singapore consists of 63 islands, including the main island, Pulau Ujong.[289] There are two man-made connections to Johor, Malaysia: the Johor–Singapore Causeway in the north and the Tuas Second Link in the west. Jurong Island, Pulau Tekong, Pulau Ubin and Sentosa are the largest of Singapore's smaller islands. The highest natural point is Bukit Timah Hill at 163.63 m (537 ft).[290] Under British rule, Christmas Island and the Cocos Islands were part of Singapore, and both were transferred to Australia in 1957.[291][292][293] Pedra Branca is the nation's easternmost point.[294]

Land reclamation projects have increased Singapore's land area from 580 km2 (220 sq mi) in the 1960s to 710 km2 (270 sq mi) by 2015, an increase of some 22% (130 km2).[295] The country is projected to reclaim another 56 km2 (20 sq mi).[296] Some projects involve merging smaller islands through land reclamation to form larger, more functional and habitable islands, as has been done with Jurong Island.[297] The type of sand used in reclamation is found in rivers and beaches, rather than deserts, and is in great demand worldwide. In 2010 Singapore imported almost 15 million tons of sand for its projects, the demand being such that Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam have all restricted or barred the export of sand to Singapore in recent years. As a result, in 2016 Singapore switched to using polders for reclamation, in which an area is enclosed and then pumped dry.[298]

Nature

Singapore's urbanisation means that it has lost 95% of its historical forests,[299] and now over half of the naturally occurring fauna and flora in Singapore is present in nature reserves, such as the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and the Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, which comprise only 0.25% of Singapore's land area.[299] In 1967, to combat this decline in natural space, the government introduced the vision of making Singapore a "garden city",[300] aiming to improve quality of life.[301] Since then, nearly 10% of Singapore's land has been set aside for parks and nature reserves.[302] The government has created plans to preserve the country's remaining wildlife.[303] Singapore's well known gardens include the Singapore Botanic Gardens, a 165-year-old tropical garden and Singapore's first UNESCO World Heritage Site.[304]

Climate

Singapore has a tropical rainforest climate (Köppen: Af) with no distinctive seasons, uniform temperature and pressure, high humidity, and abundant rainfall.[305][306] Temperatures usually range from 23 to 32 °C (73 to 90 °F). While temperature does not vary greatly throughout the year, there is a wetter monsoon season from November to February.[307]

From July to October, there is often haze caused by bush fires in neighbouring Indonesia, usually from the island of Sumatra.[308] Singapore follows the GMT+8 time zone, one hour ahead of the typical zone for its geographical location.[309] This causes the sun to rise and set particularly late during February, where the sun rises at 7:15 am and sets around 7:20 pm. During July, the sun sets at around 7:15 pm. The earliest the sun rises and sets is in late October and early November when the sun rises at 6:46 am and sets at 6:50 pm.[310]

Singapore recognises that climate change and rising sea levels in the decades ahead will have major implications for its low-lying coastline. It estimates that the nation will need to spend $100 billion over the course of the next century to address the issue. In its 2020 budget, the government set aside an initial $5 billion towards a Coastline and Flood Protection Fund.[311][312] Singapore is the first country in Southeast Asia to levy a carbon tax on its largest carbon-emitting corporations producing more than 25,000 tons of carbon dioxide per year, at $5 per ton.[313]

To reduce the country's dependence on fossil fuels, it has ramped up deployment of solar panels on rooftops and vertical surfaces of buildings, and other initiatives like building one of the world's largest floating solar farms at Tengeh Reservoir in Tuas.[314]

| Climate data for Singapore (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1929–1941 and 1948–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.2 (95.4) |

35.2 (95.4) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.8 (96.4) |

36.5 (97.7) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.0 (93.2) |

34.2 (93.6) |

34.4 (93.9) |

34.6 (94.3) |

34.4 (93.9) |

33.8 (92.8) |

36.0 (96.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.6 (87.1) |

31.5 (88.7) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.4 (90.3) |

32.3 (90.1) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.8 (89.2) |

31.2 (88.2) |

30.5 (86.9) |

31.6 (88.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.8 (80.2) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.8 (82.0) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.8 (80.2) |

27.8 (82.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 24.3 (75.7) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.9 (76.8) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.0 (77.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 19.4 (66.9) |

19.7 (67.5) |

20.2 (68.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.8 (69.4) |

19.7 (67.5) |

20.2 (68.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

20.6 (69.1) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

19.4 (66.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 221.6 (8.72) |

105.1 (4.14) |

151.7 (5.97) |

164.3 (6.47) |

164.3 (6.47) |

135.3 (5.33) |

146.6 (5.77) |

146.9 (5.78) |

124.9 (4.92) |

168.3 (6.63) |

252.3 (9.93) |

331.9 (13.07) |

2,113.2 (83.20) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 13 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 15 | 19 | 19 | 171 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83.5 | 81.2 | 81.7 | 82.6 | 82.3 | 80.9 | 80.9 | 80.7 | 80.7 | 81.5 | 84.9 | 85.5 | 82.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 180.4 | 198.6 | 196.6 | 182.4 | 184.8 | 175.4 | 188.5 | 184.6 | 161.4 | 155.0 | 133.2 | 133.1 | 2,074 |

| Source 1: National Environment Agency[315][316] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun only, 1991–2020)[317] | |||||||||||||

Water supply

Singapore considers water a national security issue and the government has sought to emphasise conservation.[318] Water access is universal and of high quality, though the country is projected to face significant water-stress by 2040.[319][320] To circumvent this, the Public Utilities Board has implemented the "four national taps" strategy – water imported from neighbouring Malaysia, urban rainwater catchments, reclaimed water (NEWater) and seawater desalination.[321] Singapore's approach does not rely only on physical infrastructure; it also emphasises proper legislation and enforcement, water pricing, public education as well as research and development.[322] Singapore has declared that it will be water self-sufficient by the time its 1961 long-term water supply agreement with Malaysia expires in 2061. However, according to official forecasts, water demand in Singapore is expected to double from 1.4 to 2.8 billion litres (1.4 to 2.8 million cubic metres; 370 to 740 million US gallons) per day between 2010 and 2060. The increase is expected to come primarily from non-domestic water use, which accounted for 55% of water demand in 2010 and is expected to account for 70% of demand in 2060. By that time, water demand is expected to be met by reclaimed water at the tune of 50% and by desalination accounting for 30%, compared to only 20% supplied by internal catchments.[323][324]

Singapore is expanding its recycling system and intends to spend S$10 billion (US$7.4 billion) in water treatment infrastructure upgrades.[325] The Ulu Pandan wastewater treatment was specially built to test advanced used-water treatment processes before full deployment and won the Water/Wastewater Project of the Year Award at the 2018 Global Water Awards in Paris, France.[326] Operation started in 2017 and was jointly developed by PUB and the Black & Veatch + AECOM Joint Venture.[327]

Virtual Singapore

Virtual Singapore is a 3D digital replica of Singapore, which is used by the Government of Singapore, Singapore Land Authority, and many more companies to plan for industrial changes. It is also used for disaster management.[citation needed]

Transport

Land

Singapore has a road system covering 3,356 kilometres (2,085 mi), which includes 161 kilometres (100 mi) of expressways.[328][329] The Singapore Area Licensing Scheme, implemented in 1975, became the world's first congestion pricing scheme, and included other complementary measures such as stringent car ownership quotas and improvements in mass transit.[330][331] Upgraded in 1998 and renamed Electronic Road Pricing (ERP), the system introduced electronic toll collection, electronic detection, and video surveillance technology.[332] A satellite-based system was due to replace the physical gantries by 2020, but has been delayed until 2026 due to global shortages in the supply of semiconductors.[333] As Singapore is a small island with a high population density, the number of private cars on the road is restricted with a pre-set car population quota, to curb pollution and congestion. Car buyers must pay for Additional Registration Fees (ARF) duties of either 100%, 140%, 180% or 220% of the vehicle's Open Market Value (OMV), and bid for a Singaporean Certificate of Entitlement (COE) (that varies twice a month in supply based on the number of car registrations and de-registrations), which allows the car to be driven on the road for maximum period of 10 years. Car prices are generally significantly higher in Singapore than in other English-speaking countries.[334] As with most Commonwealth countries, vehicles on the road and people walking on the streets keep to the left (left-hand traffic).[335]

Singapore's public transport network is shaped up with trains (consisting of the MRT and LRT systems), buses and taxis. There are currently six MRT lines (North–South MRT line, East–West MRT line, North East MRT line, Circle MRT line, Downtown MRT line and Thomson–East Coast MRT line), three LRT lines serving the neighbourhoods of Bukit Panjang and Choa Chu Kang (Bukit Panjang LRT line), Sengkang (Sengkang LRT line) and Punggol (Punggol LRT line),[336] covering around 241 km (150 mi) in total, and more than 300 bus routes in operation.[337] Taxis are a popular form of transport as the fares are relatively affordable when compared to many other developed countries, whilst cars in Singapore are the most expensive to own worldwide.[338]

The Johor–Singapore Causeway (connecting Singapore with Johor Bahru, Malaysia) is the busiest international land border crossing in the world, whereby approximately 350,000 travellers cross the border checkpoints of both Woodlands Checkpoint and Sultan Iskandar Building daily (with an annual total of 128 million travellers).[339]

The Land Transport Authority (LTA) is responsible for all land transport-related infrastructure and operations in Singapore.

Air

Singapore is a major international transport hub in Asia, serving some of the busiest sea and air trade routes. Changi Airport is an aviation centre for Southeast Asia and a stopover on Qantas' Kangaroo Route between Sydney and London.[340] There are two civilian airports in Singapore, Changi Airport and Seletar Airport.[341][342] The Changi Airport hosts a network of over 100 airlines connecting Singapore to some 300 cities in about 70 countries and territories worldwide.[343] It has been rated one of the best international airports by international travel magazines, including being rated as the world's best airport for the first time in 2006 by Skytrax.[344] It also had the second- and third-busiest international air routes in the world; the Jakarta-Singapore airport pair had 4.8 million passengers carried in 2018, whilst the Singapore-Kuala Lumpur airport pair had 4.5 million passengers carried in 2018, both trailing only behind Hong Kong-Taipei (6.5 million).[citation needed]

Singapore Airlines, which is the flag carrier of Singapore,[345] has been regarded as a 5-star airline by Skytrax[346] and been in the world top 10 list of airlines for multiple consecutive years.[347] It held the title of the World's Best Airline by Skytrax in 2023. It won this title 12 times. Its hub, Changi Airport had also been rated as the world's best airport from 2013 to 2020 before being superseded by Hamad International Airport in Doha.[348] It reclaimed this title in 2023[349] before being superseded once more in 2024.[350]

Sea

The Port of Singapore, managed by port operators PSA International and Jurong Port, was the world's second-busiest port in 2019 in terms of shipping tonnage handled, at 2.85 billion gross tons (GT), and in terms of containerised traffic, at 37.2 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs).[351] It is also the world's second-busiest, behind Shanghai, in terms of cargo tonnage with 626 million tons handled. In addition, the port is the world's busiest for transshipment traffic and the world's biggest ship refuelling centre.[352]

Industry sectors

Singapore is the world's 3rd-largest foreign exchange centre, 6th-largest financial centre,[353] 2nd-largest casino gambling market,[354] 3rd-largest oil-refining and trading centre, largest oil-rig producer and hub for ship repair services,[355][356][357] and largest logistics hub.[358] The economy is diversified, with its top contributors being financial services, manufacturing, and oil-refining. Its main exports are refined petroleum, integrated circuits, and computers,[359] which constituted 27% of the country's GDP in 2010. Other significant sectors include electronics, chemicals, mechanical engineering, and biomedical sciences. Singapore was ranked 4th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024 and 7th in 2022.[360][361][362][363][364] In 2019, there were more than 60 semiconductor companies in Singapore, which together constituted 11% of the global market share. The semiconductor industry alone contributes around 7% of Singapore's GDP.[365]

Singapore's largest companies are in the telecommunications, banking, transportation, and manufacturing sectors, many of which started as state-run statutory corporations and have since been publicly listed on the Singapore Exchange. Such companies include Singapore Telecommunications (Singtel), Singapore Technologies Engineering, Keppel Corporation, Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation (OCBC), Development Bank of Singapore (DBS), and United Overseas Bank (UOB). In 2011, amidst the global financial crisis, OCBC, DBS and UOB were ranked by Bloomberg Businessweek as the world's 1st, 5th, and 6th strongest banks in the world, respectively.[366] It is home to the headquarters of 3 Fortune Global 500 companies, the highest in the region.[367]

The nation's best known global companies include Singapore Airlines, Changi Airport, and the Port of Singapore, all of which are among the most-awarded in their respective fields. Singapore Airlines was ranked as Asia's most-admired company, and the world's 19th most-admired company in 2015 by Fortune's annual "50 most admired companies in the world" industry surveys. Other awards it has received include the US-based Travel + Leisure's Best International Airline award, which it has won for 20 consecutive years.[368][369] Changi Airport connects over 100 airlines to more than 300 cities. The strategic international air hub has more than 480 World's Best Airport awards as of 2015[update], and is known as the most-awarded airport in the world.[370] Over ten free-trade agreements have been signed with other countries and regions.[185] Singapore is the second-largest foreign investor in India.[371] It is the 14th largest exporter and the 15th largest importer in the world.[372][373]

Tourism

Tourism is a major industry and contributor to the Singaporean economy, attracting 13.6 million international tourists in 2023, more than double Singapore's total population.[374] Tourism contributed directly to about 3% of Singapore's GPD, on average, in the 10 years before 2023, excluding the Covid-19 pandemic years.[375] Altogether, the sector generated approximately 8.6% of Singapore's employment in 2016.[376]

In 2015, Lonely Planet and The New York Times listed Singapore as their top and 6th-best world destinations to visit, respectively.[377] Well-known landmarks include the Merlion,[378] the Esplanade,[379] Marina Bay Sands,[380] Gardens by the Bay,[381] Jewel Changi Airport,[382] CHIJMES,[379] National Gallery Singapore,[379] the Singapore Flyer,[379] the Orchard Road shopping belt,[383] the resort island of Sentosa,[384] and the Singapore Botanic Gardens, Singapore's first UNESCO World Heritage Site,[385] all located in southern and eastern Singapore.

The Singapore Tourism Board (STB) is the statutory board under the Ministry of Trade and Industry which is tasked with the promotion of the country's tourism industry. In August 2017 the STB and the Economic Development Board (EDB) unveiled a unified brand, Singapore – Passion Made Possible, to market Singapore internationally for tourism and business purposes.[386] The Orchard Road district, which contains multi-storey shopping centres and hotels, can be considered the centre of shopping and tourism in Singapore.[383] Other popular tourist attractions include the Singapore Zoo, River Wonders, Bird Paradise and Night Safari (located in Northern Singapore). The Singapore Zoo has embraced the open zoo concept whereby animals are kept in enclosures, separated from visitors by hidden dry or wet moats, instead of caging the animals, and the River Wonders has 300 species of animals, including numerous endangered species.[387] Singapore promotes itself as a medical tourism hub, with about 200,000 foreigners seeking medical care there each year. Singapore medical services aim to serve at least one million foreign patients annually and generate US$3 billion in revenue.[388]

Demographics

As of mid-2023, the estimated population of Singapore was 5,917,600, of whom 3,610,700 (61.6%) were citizens and the remaining 2,306,900 (38.4%) were either permanent residents (522,300) or international students, foreign workers, or dependants (1,644,500).[389] The overall population increased 5% from the prior year, driven largely by foreign workers.[390] According to the country's most recent census in 2020, nearly one in four residents (citizens and permanent residents) was foreign born; including non-residents, roughly 43% of the total population was born abroad.[391] This proportion is largely unchanged from the 2010 census.[392][393]

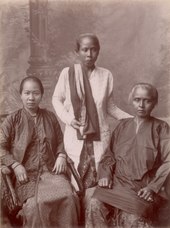

The 2020 census reported that about 74.3% of residents were of Chinese descent, 13.5% of Malay descent, 9.0% of Indian descent, and 3.2% of other descent (such as Eurasian); this proportion was virtually identical to the 2010 census, with slight increases among Chinese and Malay (0.2% and 0.1% respectively) and minor decreases in Indian and others (0.2% and 0.1%).[394][392] Prior to 2010, each person could register as a member of only one race, by default that of his or her father; therefore, mixed-race persons were solely grouped under their father's race in government censuses. From 2010 onward, people may register using a multi-racial classification, in which they may choose one primary race and one secondary race, but no more than two.[395]

Like other developed countries in Asia, Singapore experienced a rapid decline in its total fertility rate (TFR) beginning in the 1980s.[396] Since 2010, its TFR has largely plateaued at 1.1 children per woman, which is among the lowest in the world and well below the 2.1 needed to replace the population.[397] Consequently, the median age of Singaporean residents is among the highest in the world, at 42.8 in 2022 compared to 39.6 ten years earlier.[398] Starting in 2001, the government introduced a series of programs to increase fertility, including paid maternity leave, childcare subsidies, tax relief and rebates, one-time cash gifts, and grants for companies that implement flexible work arrangements;[396] nevertheless, live births have continued to decline, hitting a record low in 2022.[399] Singapore's immigration policy is designed to alleviate the decline and maintain its working-age population.[400][401][402]

91% of resident households (i.e. households headed by a Singapore citizen or permanent resident) own the homes they live in, and the average household size is 3.43 persons (which include dependants who are neither citizens nor permanent residents).[403][404] However, due to scarcity of land, 78.7% of resident households live in subsidised, high-rise, public housing apartments developed by the Housing and Development Board (HDB). Also, 75.9% of resident households live in properties that are equal to, or larger than, a four-room (i.e. three bedrooms plus one living room) HDB flat or in private housing.[405][406] Live-in foreign domestic workers are quite common in Singapore, with about 224,500 foreign domestic workers there, as of December 2013.[407]

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bedok  Tampines |

1 | Bedok | East | 279,510 | 11 | Ang Mo Kio | North-East | 161,180 |  Jurong West  Sengkang |

| 2 | Tampines | East | 274,360 | 12 | Bukit Merah | Central | 149,530 | ||

| 3 | Jurong West | West | 259,740 | 13 | Pasir Ris | East | 146,930 | ||

| 4 | Sengkang | North-East | 257,190 | 14 | Bukit Panjang | West | 138,940 | ||

| 5 | Woodlands | North | 255,390 | 15 | Toa Payoh | Central | 134,610 | ||

| 6 | Hougang | North-East | 227,610 | 16 | Serangoon | North-East | 118,780 | ||

| 7 | Yishun | North | 228,910 | 17 | Geylang | Central | 114,750 | ||

| 8 | Choa Chu Kang | West | 191,480 | 18 | Sembawang | North | 109,120 | ||

| 9 | Punggol | North-East | 194,750 | 19 | Kallang | Central | 100,870 | ||

| 10 | Bukit Batok | West | 168,560 | 20 | Queenstown | Central | 99,690 | ||

Religion

Most major religious denominations are present in Singapore, with the Inter-Religious Organisation, Singapore (IRO) recognising 10 major religions in the city state.[408] A 2014 analysis by the Pew Research Center found Singapore to be the world's most religiously diverse nation, with no single religion claiming a majority.[409]

Buddhism is the most widely practised religion, with 31% of residents declaring themselves adherents in the 2020 census. Christianity was the second largest religion at 18.9%, followed by Islam (15.6%), Taoism and Chinese Traditional Beliefs (8.8%) and Hinduism (5.0%). One-fifth of the population had no religious affiliation. The proportion of Christians, Muslims, and the nonreligious slightly increased between 2010 and 2020, while the proportion of Buddhists and Taoists slightly decreased; Hinduism and other faiths remained largely stable in their share of the population.[410]

Singapore hosts monasteries and Dharma centres from all three major traditions of Buddhism: Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana. Most Buddhists in Singapore are Chinese and adhere to the Mahayana tradition,[411] owing to decades of missionary activity from China. However, Thailand's Theravada Buddhism has seen growing popularity among the populace (not only the Chinese) during the past decade. Soka Gakkai International, a Japanese Buddhist organisation, is practised by many people in Singapore, and mostly by those of Chinese descent. Tibetan Buddhism has also made slow inroads into the country in recent years.[412]

Languages

Singapore has four official languages: English, Malay, Mandarin, and Tamil.[413]

English is the lingua franca[414][415][416][417] and the main language used in business, government, law and education.[418][419] The Constitution of Singapore and all government legislation is written in English, and interpreters are required if a language other than English is used in the Singaporean courts.[420][421] Statutory corporations conduct their businesses in English, while any official documents written in a non-English official language such as Malay, Mandarin, or Tamil are typically translated into English to be accepted for use.[422][415][423]

Malay was designated as a national language by the Singaporean government after independence from Britain in the 1960s to avoid friction with Singapore's Malay-speaking neighbours of Malaysia and Indonesia.[172] It has a symbolic, rather than functional purpose.[413][424][425] It is used in the national anthem Majulah Singapura,[426] in citations of Singaporean orders and decorations and in military commands.[427][428] Singaporean Malay is officially written in the Latin-based Rumi script, though some Singaporean Malays also learn the Arabic-based Jawi script.[429] Jawi is considered an ethnic script for use on Singaporean identity cards.[430]

Singaporeans are mostly bilingual, typically with English as their common language and their mother-tongue as a second language taught in schools, in order to preserve each individual's ethnic identity and values. According to the 2020 census, English was the language most spoken at home, used by 48.3% of the population; Mandarin was next, spoken at home by 29.9%.[428][431] Nearly half a million speak other ancestral Southern varieties of Chinese, mainly Hokkien, Teochew, and Cantonese, as their home language, although the use of these is declining in favour of Mandarin or just English.[432] Singapore Chinese characters are written using simplified Chinese characters.[433]

Singaporean English is largely based on British English, owing to the country's status as a former crown colony.[434][435] However, forms of English spoken in Singapore range from Standard Singapore English to a colloquial form known as Singlish, which is discouraged by the government as it claims it to be a substandard English creole that handicaps Singaporeans, presenting an obstacle to learning standard English and rendering the speaker incomprehensible to everyone except to another Singlish speaker.[436] Standard Singapore English is fully understandable to all Standard English speakers, while most English-speaking people do not understand Singlish. Nevertheless, Singaporeans have a strong sense of identity and connection to Singlish, whereby the existence of Singlish is recognised as a distinctive cultural marker for many Singaporeans.[437] As such, in recent times, the government has tolerated the diglossia of both Singlish and Standard English (only for those who are fluent in both), whilst continuously reinforcing the importance of Standard English amongst those who speak only Singlish (which is not mutually intelligible with the Standard English of other English-speaking countries).[437]

Education

Education for primary, secondary, and tertiary levels is mostly supported by the state. All institutions, public and private, must be registered with the Ministry of Education (MOE).[438] English is the language of instruction in all public schools,[439] and all subjects are taught and examined in English except for the "mother tongue" language paper.[440] While the term "mother tongue" in general refers to the first language internationally, in Singapore's education system, it is used to refer to the second language, as English is the first language.[441][442] Students who have been abroad for a while, or who struggle with their "Mother Tongue" language, are allowed to take a simpler syllabus or drop the subject.[443][444]

Education takes place in three stages: primary, secondary, and pre-university education, with the primary education being compulsory. Students begin with six years of primary school, which is made up of a four-year foundation course and a two-year orientation stage. The curriculum is focused on the development of English, the mother tongue, mathematics, and science.[445][446] Secondary school lasts from four to five years, and is divided between Express, Normal (Academic), and Normal (Technical) streams in each school, depending on a student's ability level.[447] The basic coursework breakdown is the same as in the primary level, although classes are much more specialised.[448] Pre-university education takes place at either the 21 Junior Colleges or the Millennia Institute, over a period of two and three years respectively.[449] As alternatives to pre-university education, however, courses are offered in other post-secondary education institutions, including the 5 polytechnics and 3 ITE colleges. Singapore has six public universities,[450] of which the National University of Singapore and Nanyang Technological University are among the top 20 universities in the world.[451]

National examinations are standardised across all schools, with a test taken after each stage. After the first six years of education, students take the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE),[445] which determines their placement at secondary school. At the end of the secondary stage, O-Level or N-Level exams are taken;[452] at the end of the following pre-university stage, the GCE A-Level exams are taken.[453] Some schools have a degree of freedom in their curriculum and are known as autonomous schools, for secondary education level and above.[447]

Singapore is also an education hub, with more than 80,000 international students in 2006.[454] 5,000 Malaysian students cross the Johor–Singapore Causeway daily to attend schools in Singapore.[455] In 2009, 20% of all students in Singaporean universities were international students—the maximum cap allowed, a majority from ASEAN, China and India.[456]