Cobb (film)

| Cobb | |

|---|---|

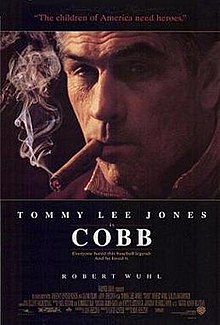

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ron Shelton |

| Screenplay by | Ron Shelton |

| Based on | Cobb: The Life and Times of the Meanest Man in Baseball by Al Stump |

| Produced by | David V. Lester |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Russell Boyd |

| Edited by | Kimberly Ray Paul Seydor |

| Music by | Elliot Goldenthal |

Production companies | Regency Enterprises Alcor Films |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 128 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25.5 million[1] |

| Box office | $1,007,600 |

Cobb is a 1994 American biographical sports drama film starring Tommy Lee Jones as baseball player Ty Cobb. The film was written and directed by Ron Shelton and based on a 1994 book by Al Stump. The original music score was composed by Elliot Goldenthal. The film is told through the partnership between Cobb and sportswriter Al Stump who served as a ghostwriter of Cobb's autobiography. Some critics lauded the film and Jones's performance, but the box office results for the film were underwhelming, grossing little over $1 million on a budget of $25.5 million.[1][2]

Plot

[edit]In 1960, sportswriter Al Stump is hired as the ghostwriter for an authorized autobiography of baseball player Tyrus Raymond "Ty" Cobb. Now 74 and in failing health, Cobb wants an official biography to "set the record straight" before he dies. In addition, Stump will get to accompany Cobb at the annual Baseball Hall of Fame ceremony in Cooperstown, New York, where Cobb is due to be inducted.

Stump arrives at Cobb's estate on Lake Tahoe, where he finds Cobb to be a continually-drunken, misanthropic and bitter racist who abuses everyone he comes in contact with. Even though Cobb's darker reputation was already a known secret by many, including Stump, the sportswriter is still shocked at the length of Cobb's behavior and ill temper when seen at face value. Although Cobb's home is luxurious, it is without heat, power, and running water due to long-running violent disputes between Cobb and utility companies. Cobb also rapidly runs through domestic workers, hiring and firing them in quick succession. Although Cobb is seriously ill and prone to frequent physical breakdowns, including sexual impotence, he retains considerable strength and also keeps several loaded firearms within easy reach at almost all times, making the outbreak of violent confrontation a constant possibility. Stump finds himself butting heads with Cobb from the first day of the job, when the two men differ on the structure of the book, with Cobb wanting to empatize his self-proclaimed greatness, while Stump argues that Cobb can't call himself great, but needs to rely on others proclaiming his greatness.

Before heading for Cooperstown, Cobb plans a quick trip for him and Stump to Reno for fun. Cobb almost gets killed in an automobile accident off the Donner Pass, driving recklessly in a blizzard. Stump rescues him, but Cobb then seizes control of Stump's car until he gets into another accident. The car has to be towed to Reno. There, Stump and Cobb see a show at a resort hotel featuring Keely Smith and Louis Prima, whose act Cobb rudely interrupts.

One morning, Cobb comes into Stump's hotel room and looks at some notes Stump had written that decry the ballplayer as "pathetic" and "lost in the past". In a rage, Cobb argues with Stump that people aren't interested in Cobb's personal issues. Only his achievements as a great player are important. He then gleefully reveals that Stump's agents agreed, behind the writer's back, to allow Cobb final editorial approval on his book, breaking the standard clause Stump has in his contract. Despite Cobb's preferred vision for the book, the player does start opening up to Stump about the pivotal event of his life, the death of his father by his mother, which he tells Stump was a result of his dad's jealous personality.

A cigarette girl, Ramona, becomes interested in Stump, but when Cobb barges into the hotel room, he's in a jealous rage. He knocks Stump out, takes Ramona to another room, where he physically abuses her, while still failing to achieve sexual arousal. Stump comes to just in time to see Ramona storm out of Cobb's room, viciously mocking the player as "Georgia trash." Horrified with what he's seen of Cobb since meeting him, Stump decides to focus on writing the true story of Cobb, instead of Cobb's intended version.

Aware of Cobb's editorial approval, Stump writes two books concurrently, the one Cobb expects ("My Life in Baseball") and a sensational, merciless account that will reveal the real Cobb, warts and all. Stump continues writing notes for the expose on different forms of hotel stationery, including hotel napkins which he hides. Stump then places the typewritten pages of "My Life in Baseball" on his workspace for Cobb to see and approve. Stump plans to complete Cobb's version while the old man is still alive, guaranteeing his payment for the project without violating Cobb's approval clause, and letting Cobb die happy. Stump will then issue the hard-hitting follow-up after Cobb is gone.

As Cobb and Stump resume the road trip, the two work on Cobb's book during the day, while Stump works on his book late at night, as Cobb sleeps. Stump soon goes from just being Cobb's ghostwriter to a general caretaker for the player, making sure Ty takes his various medications during the trip. Stump is amazed by the ill Cobb seeming to maintain some vitality despite his various ailments, which include cancer.

Cobb and Stump finally reach the Hall of Fame's induction weekend in Cooperstown, New York, where many star players from Cobb's era are in attendance, including Rogers Hornsby and Mickey Cochrane. In the runup to the dinner, Stump learns that Cobb has secretly been financially helping some old former teammates who have been struggling, which further shows layers to Cobb's person. During the Hall of Fame dinner, A hallucinating Cobb becomes haunted by images from his violent past as he views film footage of his career. Despite publicly honoring Cobb, many of the same players attending the dinner block Cobb out of their private hotel afterparties, having been fed up with his bad behavior. From Cooperstown, Cobb and Stump drive south to Cobb's native Georgia, where his estranged daughter refuses to see him, which Cobb later tells Stump is the same case with the rest of his surviving children and his ex-wives.

Continuing to write his dual accounts, Stump starts drinking heavily himself as he realizes that by doing his secret book and Cobb's book concurrently, Stump was becoming what Cobb, for all his faults, wasn't; a liar.

Despite still seeing Cobb as a man who treats people like dirt, Stump gains a grudging respect for the player's legendary intensity, competitive fire, and no-holds-barred honesty about his reputation as a tough player, taking pride in how hated he was by fellow players and even spectators. Cobb, in turn, begins to regard Stump as a friend of sorts; it is clear his conduct has driven away virtually all his legitimate friends and family. Having mockingly called Al "Al-imony" in reference to the writer's impending divorce, Cobb helps Stump finally accept that his marriage is over. Cobb also continues to open up more about his father's death, which Stump realizes was partly responsible for Cobb's antagonistic personality, despite the player's denials. Cobb finally reveals to Stump that his father's murder was not committed by his mother, as he had earlier told Stump, but by his mother's lover.

After a long night of drinking, Stump passes out. Cobb accidentally discovers Stump's notes for the no-punches-pulled version, bringing on an epic explosion.

As he aims his pistol in his mouth to kill himself, Cobb begins to seriously cough up blood and is taken to a hospital. Stump, waking up to discover Cobb saw the notes and knows the truth, finds Cobb at the hospital wielding a gun and treating doctors and nurses as harshly as he has everyone else. Cobb begrudgingly gives Stump his blessing to continue with the warts-and-all version, even admitting he respects the sportswriter for "beating" him, in a sense by fooling Cobb about his real intentions. Cobb's parting request to the sportswriter is to remember, "The desire for glory is not a sin."

Stump completes his twin books by the time Cobb passes away on July 17, 1961. As Cobb is buried alongside his parents, Stump, in voiceover, reveals that he ended up publishing the glowing autobiography Cobb hired him to write, instead of the real story.

Cast

[edit]- Tommy Lee Jones as Ty Cobb

- Robert Wuhl as Al Stump

- Lolita Davidovich as Ramona

- Lou Myers as Willie

- William Utay as Jameson

- J. Kenneth Campbell as William Herschel Cobb

- Rhoda Griffis as Amanda Chitwood Cobb

- Roger Clemens as Opposing pitcher

- Stephen Mendillo as Mickey Cochrane

- Tommy Bush as Rogers Hornsby

- Stacy Keach Sr. as Jimmie Foxx

- Crash Davis as Sam Crawford

- Rath Shelton as Paul Waner

- Jim Shelton as Lloyd Waner

- Reid Cruickshanks as Pie Traynor

- Eloy Casados as Louis Prima

- Paula Rudy as Keely Smith

- George P. Wilbur as Casino Security Man

- Bradley Whitford as Process Server

- Brian Patrick Mulligan as Charlie Chaplin

- Jimmy Buffett as Heckler

Production

[edit]Baseball scenes were filmed in Birmingham, Alabama at Rickwood Field,[3] which stood in for Philadelphia's Shibe Park and Pittsburgh's Forbes Field. Scenes also were filmed in Ty Cobb's actual hometown of Royston, Georgia.

Much of the Cobb location filming was in northern Nevada. The hotel check-in was at the Morris Hotel on Fourth Street in Reno. Casino, outdoor and entry shots were done outside Cactus Jack's Hotel and Casino in Carson City and outside the then-closed, now-reopened (2007) Doppelganger's Bar in Carson City.[citation needed]

Baseball announcer Ernie Harwell, a Ford Frick Award recipient, is featured as emcee at a Cooperstown, New York awards banquet. Real-life sportswriters Allan Malamud, Doug Krikorian, and Jeff Fellenzer and boxing publicist Bill Caplan appear in the movie's opening and closing scenes at a Santa Barbara bar as Stump's friends and fellow scribes.[citation needed]

Carson City free-lance photographer Bob Wilkie photographed many still scenes for Nevada Magazine, the Associated Press, and the Nevada Appeal.

Tommy Lee Jones was shooting this film when he won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for The Fugitive. As his head was already partially shaved in the front for his role as the balding, 72-year-old Cobb, the actor made light of the situation in his acceptance speech: "All a man can say at a time like this is, 'I am not really bald ... But I do have work." In addition to his partially shaved head, Jones also endured a broken ankle, suffered while practicing Cobb's distinctive slide.[4]

The film shows Cobb sharpening his spikes as a means to keep infielders from tagging him out as he ran the bases, and was accused of spiking several players who tried. Cobb, however, always denied ever spiking anyone on purpose. Tyler Logan Cobb, a descendant of Cobb's, played "Young Ty".[citation needed]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film opened in limited release in December 1994. It earned a reported $1,007,583 in the U.S., on a budget of $25.5 million, making it a box-office bomb.[1]

Critical response

[edit]Cobb currently has a 65% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 48 reviews. The site's consensus states: "Tommy Lee Jones's searing performance helps to elevate Cobb above your typical sports biopic; he's so effective, in fact, that some may find the film unpleasant."[5] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone hailed it as "one of the year's best" and Charles Taylor of Salon included it on his list of the best films of the decade. Others took a harsher view of the picture. Owen Glieberman of Entertainment Weekly gave the film a "D", claiming it to be a "noisy, cantankerous buddy picture" and presented Cobb as little more than a "septuagenarian crank". He noted that while the film had constant reminders of Cobb's records, it had little actual baseball in it, besides one flashback where Cobb is seen getting on base, then stealing third and home, and instigating a brawl with the opposing team. He explained: "By refusing to place before our eyes Ty Cobb's haunted ferocity as a baseball player, it succeeds in making him look even worse than he was."[citation needed]

Roger Ebert's review of December 2, 1994 in the Chicago Sun-Times described Cobb as one of the most original biopics ever made and including "one of Tommy Lee Jones's best performances," but he notes Stump (played by Wuhl) and his lack of development in the film. However, he also criticized the length of the film, giving it 2 stars out of 4. [6]

Year-end 'Best' lists

[edit]- 7th – Peter Rainer, Los Angeles Times[7]

- 9th – Peter Travers, Rolling Stone[8]

- Top 10 (not ranked) – George Meyer, The Ledger[9]

- Best of the year (not ranked) - Jeffrey Lyons, Sneak Previews[10]

- Honorable mention – Robert Denerstein, Rocky Mountain News[11]

Historical accuracy

[edit]In his 2015 book Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty, author Charles Leerhsen asserts that the film is based on Al Stump's 1961 and 1994 biographies of Ty Cobb, books noted for glaring inaccuracies regarding Cobb's life, as well as a True magazine article, also by Stump, published after Cobb's death. When the author Leerhsen contacted director Shelton concerning the inaccuracies, Shelton refused to provide documentation for some of the most extravagant aspects of the movie, and admitted to fabricating scenes along with "Al" because they believed it was something the real Cobb could have plausibly done in real life.[citation needed]

Previously, in 2010, an article by William R. Cobb (no relation to Ty) in the peer-reviewed The National Pastime, the official publication of the Society for American Baseball Research, had accused Al Stump of extensive forgeries of Cobb-related baseball and personal memorabilia, including personal documents and diaries. Stump even falsely claimed to possess a shotgun used by Cobb's mother to kill his father (in a well-known 1905 incident officially ascribed to Mrs Cobb having mistaken her husband for an intruder). The shotgun later came into the hands of noted memorabilia collector Barry Halper. Despite the shotgun's notoriety, official newspaper and court documents of the time clearly show Cobb's father had been killed with a pistol. The article, and later expanded book,[12] further accused Stump of numerous false statements about Cobb, not only during and immediately after their 1961 collaboration but also in Stump's later years, most of which were sensationalistic in nature and intended to cast Cobb in an unflattering light.[13] Cobb's peer-reviewed research indicates that all of Stump's works (print and memorabilia) surrounding Ty Cobb are at the very best called into question and at worst "should be dismiss(ed) out of hand as untrue".[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Ty Cobb Was Never Mr. Nice Guy". www.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ "Cobb (1994) - Box Office Mojo". www.boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- ^ "How Hollywood saved Rickwood Field". MLB.com. Retrieved 2024-06-14.

- ^ Wells, Jeffrey (April 8, 1994). "Tommy Boy". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 8, 2009.

- ^ "Cobb (1994)". rottentomatoes.com. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Cobb movie review & film summary (1994) | Roger Ebert". www.rogerebert.com. Retrieved 2019-12-25.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (December 25, 1994). "1994: YEAR IN REVIEW : No Weddings, No Lions, No Gumps". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ Travers, Peter (December 29, 1994). "The Best and Worst Movies of 1994". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ Meyer, George (December 30, 1994). "The Year of the Middling Movie". The Ledger. p. 6TO.

- ^ Lyons, Jeffrey (host); Medved, Michael (host) (January 6, 1995). "Best & Worst of 1994". Sneak Previews. Season 20. WTTW. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ Denerstein, Robert (January 1, 1995). "Perhaps It Was Best to Simply Fade to Black". Rocky Mountain News (Final ed.). p. 61A.

- ^ Cobb, William R. (2013). The Georgia Peach: Stumped by the Storyteller. William R. Cobb. p. 67. ISBN 978-1628408034.

- ^ a b William R. Cobb (2010). "The Georgia Peach: Stumped by the Storyteller". In Ken Fenster; Wynn Montgomery (eds.). The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State (PDF). Cleveland, Ohio: Society for American Baseball Research. ISBN 9781933599168. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2010. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

External links

[edit]- Cobb at IMDb

- Cobb at AllMovie

- Cobb at Box Office Mojo

- Cobb at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1994 films

- 1990s biographical drama films

- 1990s sports drama films

- American sports drama films

- American baseball films

- American biographical drama films

- Biographical films about sportspeople

- Sports films based on actual events

- Films directed by Ron Shelton

- Regency Enterprises films

- Warner Bros. films

- Films set in 1905

- Films set in 1960

- Films set in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Films shot in Alabama

- Films shot in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Films scored by Elliot Goldenthal

- Ty Cobb

- Cultural depictions of Charlie Chaplin

- Cultural depictions of baseball players

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s American films

- Films about Major League Baseball

- English-language biographical drama films

- English-language sports drama films