Susquehannock

Historical distribution of the Susquehannock language | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Estimated 2,000 in 1600; now extinct as a tribe[1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland | |

| Languages | |

| Susquehannock | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous and Roman Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), Erie, Neutral, Wendat, Wenrohronon, Petun, Tuscarora, & Cherokee |

The Susquehannock, also known as the Conestoga, Minquas, and Andaste, were an Iroquoian people who lived in the lower Susquehanna River watershed in what is now Pennsylvania. Their name means “people of the muddy river.”

The Susquehannock were first described by John Smith, who explored the upper reaches of Chesapeake Bay in 1608. The Susquehannocks were active in the fur trade and established close trading relationships with Virginia, New Sweden, and New Netherland. They were in conflict with Maryland until a treaty was negotiated in 1652, and were the target of intermittent attacks by the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois).

By the 1670s, their population had declined sharply as a result of disease and war. The Susquehannock abandoned their town on the Susquehanna River and moved south into Maryland. They erected a palisaded village on Piscataway Creek, but in September 1675, the Susquehannock were besieged by militias from Maryland and Virginia. The survivors of the siege scattered, and those who returned to the north were absorbed by the Haudenosaunee.

In the late 1680s, a group of Susquehannock and Seneca established a settlement on the Conestoga River in present-day Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, where they became known as the Conestoga. The population of this community gradually declined, and in 1763, the last members were massacred by the vigilante group known as the Paxton Boys. While there are a significant number of Indigenous people alive today of Susquehannock ancestry, the Susquehannock as a distinct cultural entity are considered extinct.

Language

[edit]The Susquehannock were an Iroquoian speaking people. Little of the language has been preserved. The chief source is the Vocabula Mahakuassica compiled by the Swedish missionary Johannes Campanius during the 1640s. Campanius's vocabulary contains about 100 words and is sufficient to show that Susquehannock is a Northern Iroquoian language, closely related to the languages of the Haudenosaunee and in particular that of the Onondaga. The language is considered extinct as of 1763 when the last remnant community of the Susquehannock was massacred at Lancaster, Pennsylvania.[3]

Names

[edit]

The Europeans who colonized the Mid-Atlantic coast of North America typically adopted the names that were used by the coastal Algonquian-speaking peoples for interior tribes. The Europeans adapted and transliterated these exonyms to fit their own languages and spelling systems, and tried to capture the sounds of the names. What the Susquehannock called themselves is not known.[4]

- The Wendat, an Iroquoian-speaking people, called these people Andastoerrhonon, meaning "people of the blackened ridge pole." The French adapted the Wendat term and called them Andaste,[5] but later referred to them as Gandastogues.[4]

- The Lenape, an Algonquian-speaking people, referred to them by an exonym, Menkwe, from which Dutch and Swedish colonists derived the name Minqua.

- The Algonquian-speaking peoples of coastal Virginia and Maryland called the tribe the Sasquesahanough, meaning "people of the muddy river." English settlers in Maryland and Virginia transliterated the Algonquian term, referring to the people as the Susquehannock.[5]

- In the eighteenth century, British colonists in Pennsylvania called them the Conestoga, referring to the settlement established on the Conestoga River about 1690. The name may be based on the Mohawk word tekanastoge, possibly meaning "place of the upright pole."[3] Conestoga may also be the anglicized form of Gandastogue which is possibly the closest to what the Susquehannock called themselves.[6]

History

[edit]Protohistory

[edit]In the late 15th and early 16th centuries the Susquehannock lived in scattered hamlets on the North Branch of the Susquehanna River in what is now Bradford County, Pennsylvania, and Tioga County, New York. Of Northern Iroquoian ancestry, the Susquehannock became culturally and linguistically distinct before 1500.[7]

A southward migration towards Chesapeake Bay began in the second half of the 16th century, possibly the result of conflict with the Haudenosaunee to the north. The shortening of the growing season during the Little Ice Age, and the desire to be closer to sources of trade goods may also have been factors.[8] The Susquehannock assimilated the Shenks Ferry people in the lower Susquehanna River valley, and established a palisaded village in present-day Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.[9] An archaeological excavation in 1931 revealed that the village (known as the Schultz Site) contained at least 26 longhouses.[10] The Schultz site was largely abandoned c. 1600 due to overcrowding and depletion of local resources. A larger fortified town was constructed near what is today Washington Boro. The town is estimated to have been 250,000 square feet in size with a population of about 1,700 people.[7]

Several smaller Susquehannock sites have been found in the upper Potomac River valley in what is now Maryland and West Virginia that date roughly from 1590 to 1610.[11] Archaeological evidence also exists for a palisaded settlement 30 miles upstream of Washington Boro in what is now Cumberland County that was occupied from about 1610 to 1620.[12]

European contact

[edit]

The first recorded European contact with the Susquehannock was in 1608 when English explorer John Smith met with a group of about 60 "gyant-like" warriors and "weroances" at the mouth of the Susquehanna River, two days journey downriver from their settlement at Washington Boro. Smith wrote of the Susquehannock, "They can make neere 600 able and mighty men, and are pallisadoed [palisaded] in their Townes to defend them from the Massawomekes, their mortal enemies." Smith also recorded that some of the Susquehannock were in possession of hatchets, knives, and brass ornaments of French origin.[7]

Significant Susquehannock involvement in the fur trade began in the 1620s. Because of their location on the Susquehanna River, the Susquehannock had access to English traders on the Chesapeake, as well as Dutch and Swedish traders on Delaware Bay. Furs, primarily beaver, were traded for cloth, glass beads, brass kettles, hawk bells, axes, hoes, and knives. Although many Europeans were hesitant to trade firearms for furs, the Susquehannocks began to obtain muskets in the 1630s.[13]

In 1626, a group of Susquehannock travelled to New Amsterdam seeking to establish a trading relationship with the Dutch. Isaack de Rasière, the Secretary of New Netherland noted that the Lenape living on the Delaware River were unable to supply furs because of Susquehannock raids.[7] The following year the Dutch established Fort Nassau on the east side of the Delaware River opposite the mouth of the Schuylkill River.[14]

To trade with the Dutch, the Susquehannock had to pass through Lenape territory. English explorer Thomas Yonge (Yong) noted that in 1634 the "people of the river" were at war with the Minquas who had "killed many of them, destroyed their corne, and burned their houses."[15] By 1638, however, the Lenape and the Susquehannock had reached an accommodation, with the later having been given access to trading posts on the Delaware. It is said that the Lenape became "subject and tributary" to the Susquehannock[10] but this is disputed.[16]

Contact with English settlers on the Chesapeake was limited until English merchant William Claiborne began trading with the Susquehannock c. 1630. Claiborne established a settlement on Kent Island in 1631 to facilitate this trade, and later erected an outpost on Palmer's Island near the mouth of the Susquehanna River.[17]

Relations with the English deteriorated following the establishment of the Province of Maryland in 1634. The new colony formed an alliance with the Piscataway, who were the frequent target of Susquehannock raids. The founding of the colony also disrupted Claiborne's trade alliance with the Susquehannock as he refused to acknowledge Maryland's authority. When a legal dispute forced Claiborne to return to England in 1637, Maryland seized Kent Island.[18]

The focus of Susquehannock trade now turned to the newly established colony of New Sweden on Delaware Bay. Swedish settlers had built Fort Christina on the west side of the bay near the mouth of the Schuylkill River in 1638. This gave them the advantage over the Dutch in the fur trade with the Susquehannock.[19]

Following a raid on a Jesuit mission in 1641, the Governor of Maryland declared the Susquehannock "enemies of the province." A few attempts were made to organize a military campaign against the Susquehannock, however, it was not until 1643 that an ill-fated expedition was mounted. The Susquehannock inflicted numerous casualties on the English and captured two of their cannon. 15 prisoners were taken and afterwards tortured to death.[16]

Alliance with Maryland, 1651–1674

[edit]

Raids on Maryland and the Piscataway continued intermittently until 1652. In the winter of 1652, the Susquehannock were attacked by the Mohawk, and although the attack was repulsed, it led to the Susquehannock negotiating the Articles of Peace and Friendship with Maryland.[16] The Susquehannock relinquished their claim to territory on either side of Chesapeake Bay, and reestablished their earlier trading relationship with the English.[20][21]

In 1660, the Susquehannock used their influence to help end the First Esopus War between the Esopus and the Dutch.[16]

An Oneida raid on the Piscataway in 1660 led Maryland to expand its treaty with the Susquehannock into an alliance. The Maryland assembly authorized armed assistance, and described the Susquehannock as "a Bullwarke and Security of the Northern Parts of this Province." 50 men were sent to help defend the Susquehannock village. Muskets, lead and powder were acquired from both Maryland and New Netherland. Despite suffering a smallpox epidemic in 1661, the Susquehannock easily withstood a siege by 800 Seneca, Cayuga and Onondaga in May 1663, and destroyed an Onondaga war party in 1666.[16]

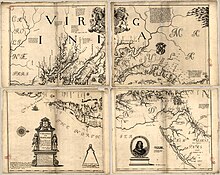

The Susquehannock abandoned their village on the east side of the Susquehanna c. 1665 and moved across the river to the west side. Their new village appears on Augustin Herrman's 1670 map of Virginia and Maryland. The Jesuit Relations for 1671 reported that the Susquehannock had 300 warriors,[22] and described a rout of a Seneca and Cayuga raiding party by a group of Susquehannock adolescents.[16]

Diaspora

[edit]By the 1670s, epidemics and years of war with the Haudenosaunee had taken their toll on the Susquehannock. In 1675, they left their village on the Susquehanna River and moved south into Maryland.

Two reasons for the move have been proposed. Most historians believe that the Haudenosaunee inflicted a major defeat on the Susquehannock c. 1674 since the Jesuit Relations for 1675 reports that the Seneca "utterly defeated ... their ancient and redoubtable foes."[7] Historian Francis Jennings, however, proposed that the Susquehannock were coerced by Maryland into moving. Jennings argued that the Haudenosaunee could not have mounted an attack in 1674 since a munitions shortage in New France meant that that the French were unable to supply them with muskets, lead and powder.[16]

Although Governor Charles Calvert of Maryland wanted the Susquehannock to settle on the Potomac River above the Great Falls, the tribe instead chose to occupy a site on Piscataway Creek where they erected a palisaded fort. In July 1675, a group of Virginians chasing Doeg raiders crossed the Potomac into Maryland and mistakenly killed several Susquehannock. Subsequent raids in Virginia and Maryland were blamed on the tribe. In September 1675, a thousand-man expedition against the Susquehannock was mounted by militia from Virginia and Maryland led by John Washington and Thomas Truman. After arriving at the Susquehannock town, Truman and Washington summoned five sachems to a parley but then had them summarily executed. Sorties during the ensuing six-week siege resulted in 50 English deaths. In early November the Susquehannock escaped the siege under cover of darkness, killing ten of the militia as they slept.[23]

Most of Susquehannock crossed the Potomac into Virginia and took refuge in the Piedmont of Virginia. Two encampments were established on the Meherrin River near the village of the Siouan-speaking Occaneechi on the Roanoke River In January 1776, the Susquehannock raided plantations on the upper Rappahannock River, killing 36 colonists, and at the falls of the James River. Nathaniel Bacon, unhappy with Governor Sir William Berkeley's response to the raids, organized a volunteer militia to hunt down the Susquehannock. Bacon persuaded the Occaneechi to attack the closest Susquehannock encampment. After the Occaneechi returned with Susquehannock prisoners, Bacon turned on his allies and indiscriminately massacred Occaneechi men, women and children.[23]

The Susquehannock who survived the Occaneechi attack moved downriver and may have merged with the Meherrin.[24]

Other Susquehannock refugees fled to hunting camps on the North Branch of the Potomac or took refuge with the Lenape. Some of these refugees returned to the lower Susquehanna River valley in 1676 and established a palisaded village near the site of their previous village.[24]

In March 1677, Susquehannock refugees living among the Lenape were invited to settle with the Haudenosaunee. While 26 families chose to remain with the Lenape, the remainder merged with the Cayuga, Oneida and Onondaga, and were joined by some of the Susquehannock from the village on the Susquehanna River. Roughly three years later the village was abandoned when the remaining inhabitants also joined the Haudenosaunee.[24]

Conestoga Town

[edit]

In the late 1680s, a group of Susquehannock and Seneca established a village near the Conestoga River in what is now Manor Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania where they became known as the Conestoga. They were later joined by a number of Oneida and Cayuga families. In 1700, William Penn, founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, visited the Conestoga and obtained from them a deed for their lands in the Susquehanna River watershed. In return, a tract of land in Manor Township was set aside for their use. This was confirmed by treaty in 1701.[7]

For the next few decades, Conestoga Town, as it came to be known, was an important trading center, and a meeting place for negotiations between Pennsylvania and various Indigenous groups. Its importance, however, waned as the focus of the fur trade and European settlement moved west. The population declined due to out-migration, and the remaining Conestoga became increasing impoverished and dependent on the Pennsylvania government, who occasionally provided clothing and provisions.[7] By the 1740s, Seneca had become the dominant language with only a few Conestoga still able to speak the "ancient tongue.".[25]

The Conestoga remained neutral during the Seven Years' War and Pontiac's War. They bartered brooms and baskets, fished, and tended their gardens. By 1763, only seven men, five women and eight children lived in Conestoga Town.[26]

In December 1763, the Paxton Boys, in response to raids by the Lenape and Shawnee during Pontiac's War attacked Conestoga Town in the mistaken belief that the inhabitants were aiding and abetting the attacks. The Paxton Boys slaughtered the six Conestoga they found there, and burned the settlement to the ground. Fourteen of the Conestoga had been absent from the village and were given shelter in the Lancaster workhouse. Two weeks later, however, the Paxton Boys broke into the workhouse and slaughtered the remaining Conestoga including women and children.[26]

Two former two inhabitants, a couple named Michael and Mary, escaped the massacre as they were living on Christian Hershey's farm near Manheim. Their burial site is recorded in the Historical Marker Database, listed as part of Kreider Homestead.[27]

In 1768, John Penn, the Governor of Pennsylvania paid the Haudenosaunee £200 in goods for the 500 acres of land on which Conestoga Town had stood. In 1775, Cayuga relatives of the Conestoga leader Sheehays received an additional payment of £300.[25]

19th century

[edit]In 1845, six Conestoga descendants living among the Oneida in New York commissioned Peter Doxtater to obtain restitution for land that had originally belonged to their ancestors in Lancaster County. Doxtater, whose maternal grandmother had lived at Conestoga Town before the massacre, later turned over all legal negotiations to Christian Shenk, an attorney in Lancaster County.[28]

An 1869 property deed shows that Doxtater bequeathed 200 acres in Lancaster County to Huldah Hall, who had been a missionary teacher among the Oneida. Hall advocated for the Conestoga descendants, and may have lobbied for the 1872 joint resolution of the United States Congress.[29] The resolution was introduced by Representative Holland Duell of New York would have recognized the remaining "Conestoga Indians" and would have returned their land on the Manor Township tract. This resolution states that a remnant of Conestoga had been with the Oneida during the massacre of 1763, and that their descendants should have use of the land set aside for them in perpetuity. The resolution died in committee.[30]

20th century

[edit]In 1941, a bill was introduced by Ray E. Taylor and William E. Habbyshaw of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives to provide a reservation for the Susquehannock in Dauphin County. The bill was triggered by the claims of "Chief Fireway" who said he was the "sole surviving chief" of 85–100 Susquehannock in Pennsylvania. The bill made arrangements for tribal members to lease land for a nominal fee and establish a central community in their historic homelands. Under the provisions of the bill, the tract of land would have been called "The Susquehannock Indian Reservation".[31] While this appropriation bill for $20,000 was passed unopposed in the state legislature, it was vetoed by Governor Arthur James, who was advised by the Pennsylvania Historical Commission that the last of the Susquehannocks had died in the 1763 massacre.[1][2]

21st century

[edit]The Conestoga-Susquehannock Tribe, an organization in Pennsylvania that self-identifies as a tribe, offers membership to those who can show documented descent from a known Susquehannock or the 1845 land claimants, for example, those descended from Skenandoa, a war leader of the Oneida during the Revolutionary War.[32] The organization is neither a federally recognized tribe[33] nor a state-recognized tribe.[34]

Those with partial Susquehannock ancestry "may be included among today's Seneca–Cayuga Nation" as well as other recognized Haudenosaunee nations in Canada and the United States.[35]

Culture

[edit]

Little ethnographic information is available about the Susquehannock due to their relative isolation from European settlement. It is widely assumed that their culture was similar to that of other Northern Iroquoian peoples: clan-based, matrilineal, semi-sedentary, and horticultural.[7]

The Susquehannock lived in semi-permanent palisaded villages that were built on river terraces and surrounded by agricultural fields. Although John Smith named six villages on his 1612 map, archaeological evidence indicates that at any one time the Susquehannock had just one or two large settlements in the lower Susquehanna River valley.[7] Roughly every 25 years, when soil fertility and nearby resources became depleted, they would move to a new location and begin anew. Until c. 1665 these villages were located on the east side of the Susquehanna River, however, from c. 1665 to 1675 the Susquehannock occupied a village on the west side of Susquehanna known as the Upper Leibhart site.[36]

Susquehannock villages contained numerous longhouses surrounded by a double palisade. Each bark-covered shelter was up to 80 feet (24 m) in length and housed as many as 60 individuals. Multiple families related through the female family line would live in one longhouse. Sons lived within this extended family household until they married, upon which time they would move to their wife's family's longhouse.[36]

Archaeological evidence from trash and burn pits indicates that the Susquehannock had a varied and seasonal diet. Maize, beans and squash were staple foods, with maize-based meals, usually in the form of soup, making up nearly half of their caloric intake. Deer was the most common animal protein but elk, black bear, fish, freshwater mussels, wild turkey and waterfowl were also eaten. Wild plants, fruits, and nuts supplemented their diets.[37]

Iroquoian people called maize, beans and squash the Three Sisters. In a technique known as companion planting, maize and climbing beans were planted together in mounds, with squash planted between the mounds.[36] Dried crops were kept in circular or bell-shaped subterranean storage pits lined with bark and dried grasses.[7]

Susquehannock women made shell-tempered pottery of various sizes primarily for cooking. Three different pottery types, corresponding to three different phases of occupation in what is now Lancaster County, have been identified. Schultz Incised is a high-collared, cordmarked pottery type that was produced until c. 1600. The collars are marked with incised lines that form geometric patterns. Schultz Incised has also been found at sites near Tioga Point. Washington Boro Incised, produced between 1600 and 1635, is similar in some respects to Schultz Incised, however, the collar is not as wide. Known as "face pots" their distinguishing feature is the presence of two to four expressionless human faces on the collars. In the mid-17th century, as European goods became more common, pot design became simpler, and many of the pots used for cooking were replaced by brass kettles. Strickler Cordmarked, produced between 1635 and 1680 lacked the collars, geometric designs and face effigies of the earlier pottery types.[38]

While Susquehannock women cultivated crops and managed the household, the men engaged in extended periods of travel for hunting, trading, and raids against neighbouring tribes. They also constructed and tended the fishing weirs that were used to catch American shad and eels.[36]

The Susquehannock relied on a network of footpaths to cross their territory. Of particular importance was the Great Minquas Path between the Susquehanna River and the Delaware River which the Susquehannock used to reach Dutch and Swedish trading posts.[39] For fishing and carrying cargoes of meat, pelts and people across the Susquehanna River, dugout canoes were used.[40]

The Susquehannock typically buried their dead in individual graves in cemeteries located outside the palisade walls. A number of multiple burials have also been found, especially at the Strickler site which was occupied from c. 1645 to c. 1665. These burials typically were of an adult and one or more children. Bodies were flexed and usually accompanied by a variety of grave goods such as bead or shell necklaces, pendants, tobacco pipes, combs, knives, clay pots, brass kettles, and occasionally gun parts.[41]

Among the gifts that Smith received from the Susquehannock in 1608 were several long-stemmed clay pipes. Tobacco was an important aspect of Susquehannock culture, but its use did not become widespread until the mid-16th century. Almost all graves dating from this period, including those of women and older children, contained pipes among the grave goods. The vocabulary compiled by Campanius includes words specifically meaning "smoking tobacco", as well as a word for "pipe for smoking tobacco." Pipes were either formed from clay or carved from soapstone. The bowls were frequently decorated with geometric designs or with human or animal effigies.[7]

Smith described the Susquehannock as "gyant-like people," however, osteoarchaeological evidence from burial sites in the lower Susquehanna River valley has not shown that the Susquehannock were exceptionally tall compared to Europeans and other Indigenous groups.[7] A recent reevaluation of the skeletal remains in the collection of Franklin & Marshall College has provided an average height for Susquehannock adult males of 174.7 centimeters (68.8 inches),[42] however, skeletal remains in England show a similar average height for adult males in the early 17th century.[43] Smith's description was based on an arranged meeting he had with 60 adult males who were likely chosen because they were physically intimidating.[42]

Legacy

[edit]

A number of locations have been named after the Susquehannock:

- Susquehannock State Park in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

- Susquehannock High School in York County, Pennsylvania.

- Susquehannock State Forest in Potter County, Pennsylvania

- The Susquehannock Camps in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania

Barry Kent's Jacob My Friend: His 17th Century Account of the Susquehannock Indians is a historical novel about Dutch fur-trader and interpreter Jacob Young who married a Susquehannock woman and had several children.

A graphic novel, documentary, and teaching material, under the title Ghost River, a project of the Library Company of Philadelphia and supported by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, addresses the Paxton massacres of 1763 and provides "interpreters and new bodies of evidence to highlight the Indigenous victims and their kin."[44]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "Big Chief James Bans Grant to County Indians". Harrisburg Telegraph, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. 1 August 1941. p. 17. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ a b "What, No Indians?". The News-Chronicle. Shippensburg, Pennsylvania. 1941-08-05. p. 3. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ a b Mithun, Marianne (1981). "Stalking the Susquehannocks". International Journal of American Linguistics. 47 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1086/465671. JSTOR 1264630. S2CID 144556910.

- ^ a b Minderhout, David Jay; Frantz, Andrea T. (2008). Invisible Indians : Native Americans in Pennsylvania. Amherst, New York: Cambria Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-1604975116.

- ^ a b Wallace, Paul A.W. (1981). Indians in Pennsylvania (2nd ed.). Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. pp. 10–13.

- ^ Kent, Barry C. (2020). "Late Woodland/Early Historic Native Americans in the Susquehanna Drainage Basin:The Susquehannocks". In Carr, Kurt William; Bergmann, Christopher A.; et al. (eds.). The Archaeology of Native Americans in Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812250787.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kent, Barry C. (1984). Susquehanna's Indians. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. ISBN 9780892710249.

- ^ Beisaw, April M. (2012). "Environmental History of the Susquehanna Valley Around the Time of European Contact". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 79 (4): 366–376. doi:10.5325/pennhistory.79.4.0366. JSTOR 10.5325/pennhistory.79.4.0366. S2CID 140510609.

- ^ Richter, Daniel K. (1990). "A Framework for Pennsylvania Indian History". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 57 (3): 226–261. JSTOR 27773387.

- ^ a b Cadzow, Donald A. (1936). Archaeological Studies of the Susquehannock Indians of Pennsylvania. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical Commission.

- ^ Robert, Wall; Lapham, Heather (2003). "Material Culture of the Contact Period in the Upper Potomac Valley: Chronological and Cultural Implications". Archaeology of Eastern North America. 31: 151–177. JSTOR 40914874.

- ^ Wyatt, Andrew (2012). "Reconsidering Early Seventeenth Century A.D. Susquehannock Settlement Patterns: Excavation and Analysis of the Lemoyne Site, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania". Archaeology of Eastern North America. 40: 71–98. JSTOR 23265136.

- ^ Youssi, Adam (2006). "The Susquehannocks' Prosperity & Early European Contact". Historical Society of Baltimore County. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- ^ Jacobs, Jaap (2015). Dutch Colonial Fortifications in North America 1614-1676 (PDF). Amsterdam: New Holland Foundation.

- ^ Myers, Albert Cook, ed. (1912). "Relation of Captain Thomas Yong 1634". Narratives of Early Pennsylvania, West New Jersey, and Delaware, 1630–1707. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 37–49.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jennings, Francis (1968). "Glory, Death, and Transfiguration: The Susquehannock Indians in the Seventeenth Century". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 112 (1): 15–53. JSTOR 986100.

- ^ Fausz, J. Frederick (2005). "Present at the Creation:The Chesapeake World That Greeted the Maryland Colonists". Maryland Historical Magazine. 100 (1): 29–47.

- ^ Pleasants, Adam (2003). "The Unlucky Rebel:" William Claiborne and the Kent Island Dispute (Honors Thesis thesis). William & Mary.

- ^ Thompson, Mark L. (2016). "New Sweden". The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Rutgers University. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ Samford, Patricia (2015-02-11). "1652 Susquehannock Treaty". Maryland History by the Object. Retrieved 2021-03-23.

- ^ Shen, Fern. "A 1652 Treaty Opens up the Story of the First Baltimoreans". Baltimore Brew. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ "Excavations". Blue Rock Heritage Center. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ a b Rice, James Douglas. "Bacon's Rebellion (1676–1677)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities. Retrieved 9 October 2023.

- ^ a b c Kruer, Matthew (2021). Time of Anarchy: Indigenous Power and the Crisis of Colonialism in Early America. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97617-7.

- ^ a b Eshleman, H. Frank (1909). Lancaster County Indians: Annals of the Susquehannock and Other Indian Tribes of the Susquehanna Territory. Lititz, Pennsylvania: Express Printing. pp. 387–389.

- ^ a b Kenny, Kevin (2009). Peaceable Kingdom Lost: The Paxton Boys and the Destruction of William Penn's Holy Experiment. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199753949.

- ^ "Kreider Homestead Historical Marker". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- ^ Brubaker, Jack (1993-12-28). "The Last of the Conestogas: Who is Descended from Lancaster's Indians?". Lancaster New Era. Lancaster, Pennsylvania. p. 11.

- ^ "200 Acres of Indian Property Willed in 1869 Document". The Post-Standard. Syracuse, New York. 1948-12-05. p. 31. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ "Conestoga Survivors Confirmed by Resolution". Intelligencer Journal. 24 April 1872. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ "Proposes Reservation For Susquehannocks in Dauphin County". The Evening News, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. May 6, 1941. p. 13. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ Brubaker, Jack (2023-03-13). "The 'Conestoga-Susquehannock tribe' includes descendants of local Indians". Lancaster Online. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ "Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible to Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs". Bureau of Indian Affairs, Interior. Federal Register. September 19, 2024. pp. 2112–16. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ "State Recognized Tribes". National Conference of State Legislatures. Archived from the original on September 1, 2022. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ^ May, Jon D. "Conestoga". The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Envisioning the Susquehannock Community". RiverRoots Heritage Blog. Susquehanna National Heritage Area. 21 November 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Strauss, Alisa Natalie (2000). Iroquoian Food Techniques and Technologies: An Examination of Susquehannock Vessel Form and Function (PhD thesis). Pennsylvania State University.

- ^ "Pots from the Past: A Look at some Native American Pottery Types of the Early Contact Period". This Week in Pennsylvania Archaeology. State Museum of Pennsylvania. December 27, 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ "Great Minquas Path". Blue Rock Heritage Center.

- ^ "Dugout Canoes on the Susquehanna". RiverRoots Heritage Blog. Susquehanna National Heritage Area. 19 May 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ Beisaw, April M. (2008). Untangling Susquehannock Multiple Burials. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

- ^ a b Becker, Marshall Joseph (2019). "Susquehannock Stature: Evidence That They Were a 'Gyant-like People'". In Raber, Paul A. (ed.). The Susquehannocks: New Perspectives on Settlement and Cultural Identity. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 9780271084763.

- ^ "Highs and Lows of an Englishman's Average Height over 2000 Years". University of Oxford. 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ "Ghost River: The Fall and Rise of the Conestoga." https://ghostriver.org/ Accessed April 21, 2022.

References

[edit]- Guss, A.L. (1883). Early Indian History on the Susquehanna: Based on Rare and Original Documents. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: L.S. Hart.

- Illnick, Joseph E. (1976). Colonial Pennsylvania: A History. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0684145650.

- Varga, Colin (Winter 2007). "Susquehannocks: Catholics in Seventeenth Century Pennsylvania". Pennsylvania Heritage Magazine. 33 (1): 6–15.

- Witthoft, John; Kinsey, W. Fred, eds. (1959). Susquehannock Miscellany. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

External links

[edit]- Conestoga in the Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

- Digital Paxton. Digital collection of primary sources and contextual essays relating to the Paxton Boys.

- History of Susquehannock State Park

- Native Lands Park, York County, Pennsylvania

- Susquehannock History by Lee Sultzman

- Susquehannock Native Landscape

- Where are the Susquehannock? at The Susquehannock Fire Ring

- Susquehannock

- Algonquian ethnonyms

- Chesapeake Bay

- Extinct Native American tribes

- Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands

- Iroquoian peoples

- Native American history of Maryland

- Native American history of New York (state)

- Native American history of Pennsylvania

- Native American history of West Virginia

- Native American tribes in Maryland

- Native American tribes in Pennsylvania

- Native American tribes in West Virginia

- Potomac River

- Native American genocide